welkom in cloudtopia!

a quick note before we begin: cloudtopia is best viewed in a browser, and if you received this newsletter as an email, you might need to open it up elsewhere to read to the end!

In “the museum gaze” and “the museum gazes back”, we talked about museums as spaces of experience, thinking about the ways that galleries create unique environments that privilege a near-sacred experience of the artworks, the interactions between art and viewer that unfold within these spaces, and also the way that art institutions often become theatres of surveillance, where visitors are watched and controlled.

This week, I want to keep thinking about these ideas as we talk about the Rijksmuseum, an Amsterdam institution that is ranked among my favourite museums to visit.

As the national museum of the Netherlands, the Rijksmuseum houses a vast, impressive collection of art, and in particular Dutch art and (art) historical objects. It dates its foundation to 1798, although over the past centuries it has seen massive changes and expansion, becoming a museum on a scale that would likely be unimaginable to visitors to its original premises, five rooms in a royal palace in the Hague. The Rijksmuseum today is in Amsterdam, with much of the construction being completed in the last 19th and early 20th centuries, updated with major renovations in the early 2010s. The building hosts numerous galleries, arranged across four floors and spanning centuries; but at its heart is one perfect experiential space…

the Gallery of Honour

This room houses many of the paintings deemed to be most valuable and essential to Dutch art history from the Rijksmuseum’s collection. The large hall is designed so that paintings are nestled in a series of small room-like nooks, where a handful of paintings can be viewed within the grand space of the larger gallery. Most of these small areas include a bench where visitors can sit and observe the paintings(although in practice the museum is often too busy to be able to truly enjoy these spaces, especially because they feature some of the most well known works in the collection and thus draw a lot of attention.) There is a balance here between the grandeur and space of the massive gallery as a whole and the intimacy of these smaller viewing spaces, where you can really take your time with a specific painting or set of paintings and experience the art in its fullness.

The Rijksmuseum website has a phenomenal digital collection where its works can be viewed, along with curatorial information and history. I would highly recommend looking through it if you are interested. The archives there are searchable and can be explored by artist, medium, subject, location in the museum, etc. — The Gallery of Honour is labelled room 2.30 in the museum, and all the works displayed in it are viewable together.

In my last newsletter on this topic, I talked a lot about the surveillance state approach to museum security found in many arts institutions like the Prado in Madrid, but the experience in the Rijksmuseum is quite different. During my most recent visit, I was surprised by the almost complete absence of security guards or docents in the large galleries. In the Gallery of Honour, we watched in shock as a visitor reached out and touched the surface of a still life painting while discussing it with their companion, to absolutely no consequence. It was a busy morning and parts of the museum were claustrophobically crowded, but there was also something nice about the sense of freedom and movement in these spaces where visitors could experience the art at their own pace, able to view, discuss, photograph, and generally interact with the works however they chose. I was particularly charmed by a group of young school children, who sat on the floor with their teachers, clustered around a museum guide who sat down just in front of a painting as she talked to them about it, everyone at the same level, but looking up at the art in interest and awe.

Experience and interaction are essential parts of keeping art alive, and a good museum space encourages and guides viewers in their engagement with history and art within the space. If you are curious about this space and want to interact more with the museum collection, the Rijksmuseum website is full of cool things, including this very fun interactive Gallery of Honour, which allows you to see interesting views of the space in 3D and navigate the room, as well as design your own gallery from the artworks in the museum’s collection, which I think is super cute! Through the gallery I linked, you will be able to get a good sense of the spaces we are discussing, and all of the paintings discussed in this newsletter(plus some others I like!) can be viewed.

Vermeer

In one of my favourite little spaces in this museum, four paintings by the great Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer are displayed. I am fascinated by his work—the soft portraits, the quiet landscapes, the tender domestic scenes—there is something I find very emotional about his works and the fragile moments they capture. I feel as if I should be holding my breath when I look at a Vermeer painting lest I disturb the scene in front of me.

Vermeer is also a figure of fascination in the art historical world, leaving behind fewer than 40 paintings in total, making his work highly valuable and sought after. In 2024, the Rijksmuseum brought together his paintings from museums and collections all over the world in a ‘once in a lifetime’ exhibit, tickets for which were completely sold out in a short period of time. A digitised version of this exhibit remains available online, allowing viewers to explore the collection through a curated virtual tour.

The experience of viewing one of these paintings is very special. Often, the viewing experience in museums that are most memorable or unique, that most require a spatial experience and confrontation between the viewer and the work are pieces of great scale—I wrote previously about my love of Diego Velazquez’ Las Meninas and the impact of the work’s immense size on the experience of viewing it and sharing sacred experiential space—but part of what makes so many of Vermeer’s paintings striking is that they are in fact quite small. They encourage us to get close, to enter their world. My favourites of his works are those that encourage us to get close, to enter their world: Het Melkmeisje(The Milkmaid)1, Woman Reading a Letter, and The Love Letter all depict women in domestic settings, where we view them mid scene, creating a sense of intimacy in our relationship as viewers to the subjects of these works.2

This effect is particularly acute in The Love Letter, where our view of the subjects of this painting is framed by a doorway and the darkened corridor leading into the room, where we see glimpses of household objects: a dividing curtain tucked away at the side, shoes left in the doorway, a broom propped against the wall. As viewers, we are kept just outside of the scene, as we watch the room where the two women are in conversation. Try as we might to get closer, to overhear their conversation, our gaze remains frozen just outside the doorway, the mystery of the love letter always just out of reach.

Rembrandt van Rijn

Throughout the rest of the Gallery are several paintings by Rembrandt van Rijn, perhaps the most famous and beloved of the Dutch masters, and its crown jewel is one of his masterpieces, De Nachtwacht(The Night Watch). The Rijksmuseum collection refers to this piece as The Night Watch Militia Company of District II under the Command of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq, but it has been referred to by many names since its completion in 1642. Many other works by the artist are also displayed in the Gallery of Honour, but placed at the far end of the long gallery, viewed only through a doorway as a viewer enters the room, in a slightly separated space, massive and imposing, this iconic painting is easily the highlight.

Rembrandt is another curious character in the history of Dutch art, where his legacy looms large. In contrast to Vermeer, his body of work includes hundreds of paintings, sketches, self portraits, and etchings, and many of his greatest works are large paintings designed to hang in grand halls. Last summer, I spent a delightful sunny afternoon in the town of Leiden where Rembrandt grew up, where beautiful houses and old walls are marked with plaques indicating where the painter spent his youth— his father’s mill, the Latin School he attended, his first studio space.

Operation Night Watch

Since 2019, Rembrandt’s masterpiece has been undergoing a massive restoration project known as Operation Night Watch.

In its almost 400 year history, the painting has been through it, to say the least. Before its acquisition by the Rijksmuseum in the late 19th century, the painting had been housed in various halls and civic spaces, it was trimmed and altered to fit certain spaces, was exposed to the elements and environmental factors in these spaces including smoke, dust, and uncontrolled climate, and it was also coated with a thick layer of varnish, which significantly changed the painted surface. It has been the victim of several attacks as well: in both 1911 and 1975 it was slashed with knives, and in 1990 it was sprayed with acid.3 With all of these factors, along with the normal aging experienced by works of art, the process of restoring the painting has been an incredibly complex and long one.

The conservation of this painting has also had the added value of generating research into the painting, allowing for new discoveries about the work’s history, its subjects, and the processes Rembrandt used to create it.4 As museum director Taco Dibbits noted when the project began, this project has provided a rare and unique opportunity to learn more about the secrets of this well known yet ever mysterious work of art:

“I have been working there for 17 years and I have never seen the top of the painting – you can’t just put a ladder in front of it. We know so little on how [Rembrandt] worked on making The Night Watch.”5

Work is still ongoing, but the progress that they have made is pretty remarkable to see, and watching the transformative process of restoration is fascinating.

Three visits

I first saw this painting in November of 2019, only a few months after Operation Night Watch began, and at the time I was slightly baffled by it. Moved from its normal display space, the painting was encased(or, as it seemed to me, trapped) in a glass box, where research equipment was set up so that those working on the project could study the painting. It felt strange and sterile to see the painting in this scientific setting, sequestered away from the glory and wonder of the gallery space and the other paintings there.

In June 2024, the painting was repositioned slightly, but could be viewed outside of its glass encasement, and it was breath taking to see it displayed in full. We pushed our way to the front of the crowd to come face to face with the figures of the painting, extended hands gesturing out toward us and the massive, ever moving crowd of museum visitors.

As of spring 2025, the painting is returned to its usual space, but is once again behind glass, slightly obscured by the tools and mechanisms of conservation. More than ever before, I notice the effects of the restoration, happening live, as certain sections of the painting have now been cleaned thoroughly and layers of varnish removed, allowing their true vibrant colours to shine through the darkness of the night long believed to hang over the painting.

Watching the Night Watch

In the essay “Eye and Mind”, Maurice Merleau-Ponty writes that “the painter's world is a visible world, nothing but visible: a world almost demented because it is complete when it is yet only partial.”6 The Night Watch is a painting that has provoked questions and curiosity for centuries, and it represents a world that feels completely distinct from our own, a partial world of visual tricks and varnished darkness and illuminated lighting that tells a story.

In the 2007 film Nightwatching and connected 2008 documentary Rembrandt’s J’Accuse, writer and director Peter Greenaway outlines what he sees as a conspiracy at play behind the painting. He suggests that Rembrandt was aware of murder plot amongst the real life members of the militia company depicted in the painting and decided to include clues and accusations hidden within the work. This conspiracy is laid out enigmatically throughout the story of Nightwatching, which also explores the life of Rembrandt and his relationships with his wife Saskia, who died during the period in which he was working on The Night Watch.

The film is beautifully made, featuring incredible set and costume design, and is composed mostly of scenes choreographed and performed theatrically as if they were a stage play. Perhaps even more interesting than its theory of conspiracy is the film’s thesis of painting as theatre. As Rembrandt is confronted by one of the conspirators:

“all the people in your painting are all actors, not real people at all… I look at you, you look at me. I’m watching you and you’re watching me. But you have pretended that the people in your painting are not being watched… an actor is a person who has been trained to pretend he is not being watched.

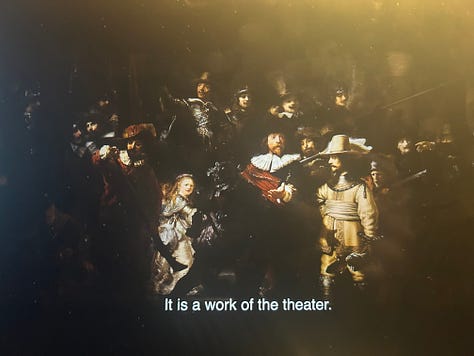

You did not fulfil the task asked of you. Your painting, Rembrandt, is dishonest. So much so, that this is not a painting at all. By its very nature, it denies being a painting. It is a work of the theatre.”

If the Night Watch is a work of theatre—be it as an accusation of hidden secrets and terrible deeds or as an imagined, valorising tableau to puff up the egos of militia men with money to spare for a famous artist—it is a work which is performed in perpetuity, with a constant stream of new audience members to watch its performance.

Yet, I disagree with the core belief that theatrical performance of the work precludes it from being a painting; rather I see it as the essence of how it operates as a painting. Like in the quiet scenes of Vermeer we discussed above, given allure by viewers trying to peer through the doorway, or the majestic drama of the scene depicted in a work like Las Meninas, this element of performance, of the story being enacted and brought to life by the engagement of painter, painting, and audience is performed by many great paintings. Whether or not the characters of The Night Watch sense they are being viewed, they are also always in the act of viewing; they act out the watch. Their gaze extends beyond the frame of the painting into our world, too, the museum gazing back.

The figures in the painting reach out to us like ghosts from beyond, their darkened world lost in history—“we see that the hand pointing to us in The Nightwatch is truly there only when we see that its shadow on the captain's body presents it simultaneously in profile.”7 Merleau-Ponty argues that to view this painting is to view the impossible—the meeting of two dimensions and three in our line of sight, whereby the interplay of light, shadow, colour, and line brings that which is, in reality only painted, into our world of experience. Through seeing—both, I think, the seeing of the painter, of Rembrandt, 400 years prior, and the seeing of countless viewers since—the painting is transformed, and undergoes a “metamorphosis…the painter’s vision is a continued birth” and further, the museum gaze “liberates the phantoms captive in [the painting],” generating new life within it.8

thank you so much for reading! if you enjoy cloudtopia, it would mean the world if you would subscribe, leave a comment, share with a friend, or create a big painting full of hidden clues toward a grand conspiracy about it <3

i hope you’ll join me again soon for more discussions of art—I think there might be one more piece in this mini-series on museums upcoming, with a little bit more about Vermeer and other dutch painters!—pop culture, and whatever else comes next!

tot ziens,

isobel

This painting has come up a few times in past newsletters and might be familiar to returning readers :)

see also: View of Delft, the fourth Vermeer painting in the Gallery of Honour, was previously mentioned in my discussion of Nosferatu(1979), which was filmed primarily in Vermeer’s hometown of Delft.

You can read more about Operation Night Watch and some of the recently published research findings on the research page of the Rijksmuseum website!

Daniel Boffey, “'Like a military operation': restoration of Rembrandt's Night Watch begins” The Guardian, 5 July 2019.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty, “Eye and Mind”, 1961, p. 166.

Merleau-Ponty, 167.

Merleau-Ponty, 167 and 168.