a quick note: cloudtopia is best viewed in a browser. if you received this newsletter via email you may need to open it elsewhere to read to the end!

I am just back from a few days in the Netherlands and so today’s newsletter will be a mix of a few things, including some Dutch museums and all things Nijntje/Miffy. This will also be the first part of a short series on art and museums including the Rijksmuseum and Mauritshuis; and to start things off, I’m going back to one of my favourite museums, the Prado in Madrid as we explore some great works of art, think about the experience of being in a museum and consider the gazes of art, artist, and art viewer.

i. nijntje’s birthday party

This year(2025) marks the seventieth anniversary of Nijnjte, a cartoon rabbit known internationally as Miffy created by artist and illustrator Dick Bruna in 1955. Her name in Dutch(Nijntje) is a diminutive form of ‘konijn’, rabbit.

Bruna was educated in art but was unsuccessful in starting a career as a traditional artist until he was later inspired to try to write a children’s book based on stories he told his son, including one about a little rabbit(konijntje) they had seen while on holiday. Miffy has appeared in numerous children’s books, illustrated and written by Bruna, as well as animated film and television appearances, and is now a veritable icon of modern children’s storytelling and graphic character design. Her silhouette is highly recognisable, and Bruna’s illustration style, which drew inspiration from Walt Disney, Matisse’s paper cutouts, and the design sensibilities of de Stijl artists including Gerrit Rietveld, influences which can be seen in the simple, thick lines, primary colours and simple colour palettes, and flat textures of Bruna’s illustrations.

In Bruna’s hometown of Utrecht, his work is featured in both the Centraal Museum and the adjacent Nijntje Museum, both of which showcase his illustrations and characters. It’s delightful to see the lasting legacy of the character in these spaces, and also to learn a bit more about Bruna’s career as an illustrator outside of the Miffy character, including his work for advertisements and book illustrations.

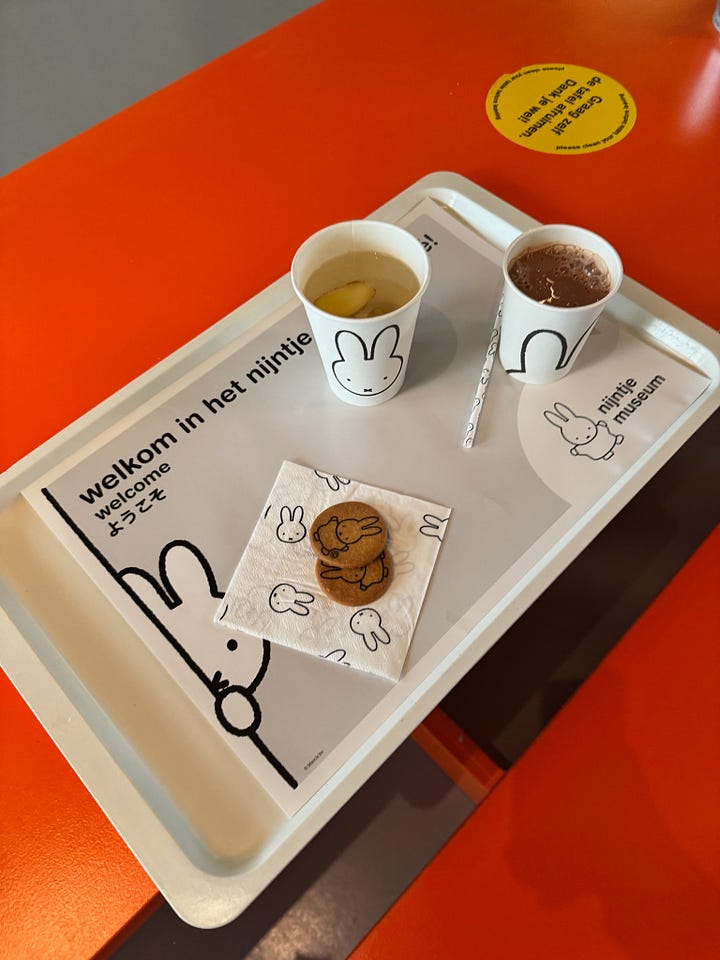

Something that struck me as I spent time in Amsterdam and elsewhere in the Netherlands was the Miffy-fication of the landscape: Bruna’s iconography is seen absolutely everywhere, in statues and public art, in shops and museums, and she even has her own pavilion at the Keukenhof Gardens. I was reminded a bit of the Moomin Industrial Complex I encountered in Helsinki last year, and the funny resurgence in recent years of these type of mascot-esque cartoon figures. And once again, I am not immune to propaganda, visiting all of the Miffy related places I could and buying the Miffy shaped almond cookies in the supermarket and returning home with a small mountain of Miffy related trinkets.

In art museums and their gift shops, Miffy has been transformed from children’s cartoon to art connoiseur through a dedicated array of kitsch. At the Rijksmuseum, Miffy takes on the role of het Melkmeisje(the Milkmaid) from the Johannes Vermeer painting of the same name while her friends Boris and Nina are transformed into one of the Night Watch(Rembrandt van Rijn, 1642) militiamen and the portrait Isabella(Simon Maris, 1906)1 respectively. Elsewhere, I’ve seen her dressed up and reimagined as Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, Piet Mondrian’s Red, Yellow, Blue paintings, and Van Gogh’s Almond Blossom. In illustrations, Miffy is depicted as a museum goer, visiting famous works. Miffy is at once object and subject of a new Dutch art history, embodying a curious relationship to art and viewership in the playfully reproduction-oriented economy of the art museum today.

ii. the museum gaze is back!

last april, I posted one of my favourite(and, I think, most popular) newsletters ever, “the museum gaze”. In thinking about some of my recent experiences in Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum and other Dutch art museums, I wanted to revisit these ideas. Think of this as a little prelude before we dig into the Rembrandts and Vermeers and other Dutch masters in our next newsletter — I hope you’ll join me then!!!

You can also read the full, original version of this piece for more on the Prado:

Each time I have visited El Museo Nacional del Prado, the experience has been a little different, yet always memorable and awe inspiring. The Prado is one of my favourite museums in the world, and contains some of my favourite paintings; yet as an institution and a space to experience works of art, it exemplifies aspects of both the best and the worst of art museums. Today, I want to think through these things a little bit by discussing the weird and often panopticon-like atmospheres cultivated by Museum Spaces, and to share a few of my favourite paintings and the way that the spatial and communal experiences of visiting a museum can influence how we view them.

the art of the panopticon

Who is a museum ‘for’? What kinds of activity and engagement are allowed within the space? What is the purpose of these spaces, and who gets to be the viewer in an art gallery?

In any museum space today, access remains a huge issue. Financial, physical, social, and cultural barriers around museums can be difficult to penetrate, and there is a lot of work to be done before museums can be spaces for all people to encounter art and history. In recent decades, these questions of the museum have been given much greater consideration, and access to art is increasingly democratised. Yet at the same time, barriers to access remain very much in place, and outdated understandings around museums and their visitors continue to play a role.

One of the most interesting ways in which museum spaces are often intentionally designed in elitist and exclusive ways is through the implementation of surveillance and security theatre.

While some degree of the security apparatus of a museum exists to protect the art contained within, there is also a lot about it that operates on a more social level. The prevalence of guards, cameras, etc. in galleries ensure that guests maintain specific standards of behaviour, and the awareness of being watched reminds visitors of their status within this space, and encourages strict regulation of behaviour - movement, sound, use of technology - to control how people engage with the institution and the works of art in a space. Museums become more and more panopticon-like as surveillance becomes more all encompassing, and visitors remain under watch everywhere in the museum, regardless of the presence of an actual guard or docent.

In the Prado, I thought a lot about these ideas around museum surveillance and the panopticon, a topic explored in some areas of art history scholarship which I was introduced to as an undergrad student. I am representative in some ways of the classical museum goer — I have the means to buy a ticket, I am a white person living in Europe, information is provided in languages that I read, I have been educated in art (it even says so on my degree, lol) and I know the typical ways viewers are expected to quietly contemplate the work — and these are all things that make museums more accessible to me. I do not have to wonder whether I belong in the space. Yet I often find myself hyperaware of the sense of surveillance in these spaces and of being watched, of having to perform good viewership for the watchful eye of the institution. Throughout my visit, I noticed it — the disdainful gaze of guards, the way that they regulated the movement of people through rooms and actively, somewhat aggressively, ensured we kept our distance. Sometimes when visitors conversed the guards would go out of their way to shush them, and there is constant reprimanding and chasing after to stop people taking photos, etc.

There is a total regulation of behaviour and movement in the galleries, all of which serves to remind us viewers that our presence in the space is conditioned.

Some prohibitions have practical reasons - flash photography is almost universally not allowed in museum spaces due to the potential harm of light exposure to many objects and works of art - but a general ban on photography has only a cultural purpose, and is far less common. One of Madrid’s other prominent museums, the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, has changed their rules to permit photography in recent years, and the presence of photography and camera phones has had no detrimental effect on the museum. I visited before the regulation was changed(where we got yelled at in spanish for not knowing the rule) and again after(where the museum space was quiet and pleasant, and people felt free to look at and photograph the works.) Other European institutions of similar stature, like the Museé du Louvre, also permit photography, which has little to no ill effect on the museum’s control over patrons or its status as a top museum globally. The regulation of photography, then, really only exists as an elitist prohibition to prevent people from engaging with work in certain ways deemed less-than.

These notions of exclusivity are prioritised in a way that, in practice, lead to more confused and unhappy visitors, and disruptions to the environment of the gallery are caused not by curious tourists but by guards shouting at and chastising people. These rules designed to preserve the status of the institution often work against themselves and instead infringe upon the experiential environment of the art space.

in a space

The means by which museum spaces and social rules are designed are really fascinating, and the sense of panoptic surveillance is just one of many sociological tools in the arsenal of museums and similar institutions to ensure spatial, social, and ideological authority is maintained. One of the touchstone pieces of writing that helped me learn to think critically about these spaces is Brian O’Doherty’s “Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space”. From the introduction:

The eternity suggested in our exhibition spaces is ostensibly that of artistic posterity, of undying beauty. of the masterpiece. But in fact it is a specific sensibility, with specific limitations and conditionings, that is so glorified.2

This text’s primary interest is modernism and the modernist sensibilities that popularised and inaugurated the titular “white cube” as the now almost universal space of exhibition, but its interrogation of the ways in which we are trained to see and understand art and the tenuous and complex relationships between ‘art’, ‘viewer’, and the contexts in which they are formed remain relevant in a multitude of gallery and exhibition spaces. These relationships are intimately connected with the regulation of behaviour, and access to museums, enacting an almost ritualistic mode of experience within that sacred space.

The ideal gallery subtracts from the artwork all cues that interfere with the fact that it is “art.” The work is isolated from everything that would detract from its own evaluations of itself. This gives the space a presence possessed by other spaces where conventions are preserved through the repetition of a closed system of values. Some of the sanctity of the church…. joins with chic design to produce a unique chamber of aesthetics. So powerful are the perceptual fields of force within this chamber that, once outside it, art can lapse into secular status.3

Museums are very much akin to sacred spaces, where placemaking is enacted and reaffirmed through specific conventions and forms of engagement. And museums often depend upon control in order to enact their missions. Their architecture demands conformity, their institutions look down on us, their very essence ensures that we experience art “correctly”.

art, alive.

But there is something to all of this, right? — something mystical about what O’Doherty refers to as the “sacramental nature” of visiting a gallery or a museum?

The Prado is one of my favourite museums in the world, and within it is one of my favourite gallery rooms, inside which is one of my favourite paintings. “Las Meninas”, painted in 1656 by Diego Velázquez, is a masterpiece.

The painting is massive in person, and takes up one wall of a huge, magnificent gallery room in the Prado’s main wing. The space of this room, which features a total of sixteen Velázquez paintings, largely portraits of and commissioned by the Spanish royal family, is full of an incredible, electric energy - this is the sacred space created when the conventions and components of the ideal gallery come together.

If you would like to view this space(or any others in the Prado!)—digitally mediated—the Prado’s website has an incredible virtual collection where the rooms can be navigated and viewed. Las Meninas is found in room 12, a decagonal chamber with a domed ceiling of glass panels and beautiful, multicoloured marble floors.

I could stand in this room forever.

meninas y nosotros

Las Meninas commands such attention, not only due to its massive scale and positioning, although these certainly play a role, but it is also the mystery of the painting that is so compelling. The central puzzle of this work is one that not only draws the attention of its viewers, but implicates us in its story and in a paradoxical, mutual gaze of seeing and being seen.

The painting depicts a group of figures recognisable from the Spanish court at the time it was painted, including the painter himself. In contrast to the majestically posed portraits on display throughout the rest of the room, Las Meninas captures a scene frozen in a moment - Velázquez is at his easel, in the midst of or preparing to begin a massive painting, while the titular meninas(ladies in waiting) group around the central figure of Infanta Margarita Teresa, and other members of the household appear mid action in the scene. There is so much to look at and try to understand in this image.

Inherently, there is something contradictory in it - why is Velázquez, painter of this painting, in the story? He is depicted painting a large scale work, staring out at the viewer. Who is he painting? While the Infanta is the central figure in Las Meninas, she does not even appear in his line of sight, so clearly he is at work on something else. In the distance, a mirror reflects two more figures, the King and Queen of Spain. Seen only in reflection, they do not appear in the plane of the painting, but instead seem to be positioned in the gallery room, standing in front of Velázquez, where we are. Viewers of the scene before us, yet subjects of a painting themselves, they occupy a space both outside of and yet intricately woven into the image presented in this painting. And in trying to unlock the complex puzzle of this image, we as viewers become entangled in it ourselves. The figures in the painting seem to be looking at us, the monarchs stand in the room with us, Velázquez might be painting us.

On a busy day in the Prado, this room is absolutely packed with visitors. When I entered the room, I spotted Las Meninas first through the doorway, then only from across the room, dozens of heads in between me and the watchful gaze of the painting. I watched it like this for a while, as people moved in and out of the room, stepped closer to the work, crowded in front of it, and it felt like the painting was alive. Here were countless new subjects for the painted Velázquez’ painting, new faces to meet the eyes of the Infanta, to notice the reflected faces of her parents, to peer after the retreating man as he leaves through a doorway we ourselves cannot reach.

By viewing this work we too are viewed, brought into its story and the long past Madrid it captures. The spaces blend together, open up, we are all mingling in this room, viewer and viewed, painter and muse, object and subject. Ultimately, it is the visitor to the museum, who comes to view Las Meninas that is the key to its mysteries, not only by taking part in its extraordinary tableau, but simply in viewing the painting, engaging it, ascribing meaning to it — we bring the work to life.

goya y el bosque

In spite of strict prohibitions on photography in the Prado, I did take a few sneaky photos, so I wanted to share with you(aside from the Velázquez gallery, which is magnificent but too carefully monitored for me to photograph) more of my favourite encounters with the works of the Prado, the connections we make, and the entangled magic that keeps art alive.

Besides the room that contains Las Meninas, my other favourite space in the Prado is a dark corridor that collects the “Black Paintings” of Spanish painter Francisco Goya4, including one of his most iconic works and one of my all time favourites, Saturn(1820-1823)5, a weird and unsettling and striking image. During my last visit, as I approached the work I watched a small child who seemed to absolutely love the painting, yelling “SATURNO” as soon as she saw and running to get closer, babbling about it to her father in baby spanish as he lifted her up to see it better.

To some, this painting is horrific, to some it is a meme,6 and to others, it is an object of joy and fascination. This is part of what makes these museums so fun - you’re seeing not just the work, but the shared experiences of people and art in the space together. These interactions give paintings life!

I am still in awe of these galleries, alive and vivid, terrible and holy. Possibly my favourite in the entire collection at the Prado is the Hieronymous Bosch triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights(1490-1510), a massive work full of endlessly bizarre and beautiful details and images. I spent nearly half an hour with this painting during my last visit, slowly looking at different parts of the triune image and uncovering as many of its funny, charming, and creepy puzzle pieces as I could. Of course, I was not the sole viewer in this space: the room was packed with other museum goers, and during this time I was constantly aware of the highly suspicious gaze of the ever-present museum security apparatus in the form of docents; it was incredible to experience this space in its fullness, over a long period of time, listening to other viewer’s conversations, moving slowly through the space, getting to see the massive work from all angles, being embodied before and together with the work of art. Each panel and its back has a unique image, and it is a work that encourages and welcomes the gaze - Bosch wants us to take time and space for this work, to try to figure it out, to be awed and delighted and disturbed by the infinite mystery of the imagery, to view it and to be challenged. Much like Las Meninas, the entanglement of viewing is essential: we gaze at the art, and the art gazes back.

iii. fashion catalogue update!

in my last newsletter I shared my process of cleaning up and cataloguing my wardrobe, and I wanted to share a quick update on how I am making use of my new system!

As you can probably infer from everything about that last newsletter, I take my outfits pretty seriously, especially when I am traveling, and I love carefully planning out everything I want to wear on holiday to optimise comfort, lots of walking, and cute photographs. Thanks to my new personal fashion catalogue, I was able to plan my outfits and consider different options with ease.

Here is my final wardrobe for this trip, plus a few of the inspirations - I went for a mostly blue and white, delftware inspired colour palette, chose knitwear with floral motifs, and other details were inspired by some of the museum artworks I visited :-)

thank you so much for reading! if you liked this discussion, it would mean the world if you would subscribe, share with a friend, or check out some of the other pieces I’ve linked in this text. Up next, we’ll be back for some more museum chat and look at other great museums and dutch masterpieces. See you then !!!

p.s. if i have any readers participating in the next papal conclave can u please put in a vote for me it’s litch my dream job. you can just put ‘isobel’ on the ballot, tysm x

tot ziens,

isobel

This beautiful portrait has gained new attention in recent years as part of the Rijksmuseum’s recent curation initiatives, as it was decided that a previous title given to this portrait in the 1970s was inappropriate and would no longer be used. In 2020, documents and notes made by the artist were rediscovered, and historians learned that he had intended to call the portrait “Isabella”, and the painting has been rechristened and is now on display under this name, as well as drawing new interest from art historians, curators, and museumgoers thanks to these new historical discoveries around its creation.

Brian O’Doherty, “Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space.” First published in Artforum, 1976.

From O’Doherty, “Inside the White Cube”, page 14.

On the virtual tour: floor 0, room 67 if you want to check these out!

This is often referred to popularly as “Saturn Devouring His Son”, but I am going with the shorter title used by the Prado.