beannachtaí na bealtaine & happy may :-)

welcome back to cloudtopia! this week I’m celebrating the start of a new month by sharing the May page of the Cloudtopia calendar(stick around to the end!). We’re taking a quick break from art and museum history to talk about another one of my recent obsessions: “artificial intelligence”.

I put this term in scare quotes because artificial intelligence as an umbrella term is one that I am very sceptical about, especially in today’s AI boom where it is being implemented in increasingly unnecessary and often harmful ways everywhere we look! Also because AI is a pretty meaningless descriptor when it is equally applied to everything from normal functions of computers(spelling and grammar check, for instance), large language models or predictive algorithms, and imaginary evil supercomputers that are going to destroy humanity. It’s a term that I find a tad problematic, to put it lightly.

Since research in the artificial intelligence field began in the 1950s, computer scientists, roboticists, and other have made big strides in developing new ways of solving problems with digital computers, and in particular in the past few decades, computer technology and our access to powerful mobile computer devices has absolutely revolutionised the possibilities for new technological capacities. One of the earliest problems proposed by early AI innovators was a simple but fascinating question: given sufficient programming to account for statistical possibilities, move sets, and gameplay rules, could a computer be developed that could play games?1

This question, although the mathematical problems behind it have now been solved, continues to be a fascinating and delightful one when we think about machine intelligence and all that it represents, both now, historically, and for our future, and it sits at a neat little intersection of the interests of computer science, statistics, game theory, and our human desire to anthropomorphise new technology.

Chess, Checkers, Go!

In 1770 Vienna, a technological marvel was unveiled: the Mechanical Turk2, an automaton that could play a game of chess against a human opponent. For decades, this incredible robot and its inventor toured Europe and wowed onlookers with its gameplay skills. While many, including writer Edgar Allen Poe3, who witnessed a demonstration chess game in the 1830s, were skeptical of the almost magical machine, it was not until the 1850s that many of the Mechanical Turk’s secrets were revealed: most importantly, that the automaton was not in fact autonomous, but powered by a human being hidden inside the mechanisms.

Of course, since then, we have seen countless variations of chess playing computers and robots, becoming increasingly sophisticated and technically complex. But with these and all forms of AI, an important lesson remains from the days of fraudulent chess automatons: there is always a human hand behind the marvels of the machine.

In the early 20th century, mathematicians working on the problem of digital computers and machine mathematics began to develop algorithms that might one day allow a machine to calculate chess moves. By the early 1950s, these were being implemented by the first generation of AI researchers, who successfully programmed computers to play simple board games like checkers, while working towards the more mathematically complex game of chess.4

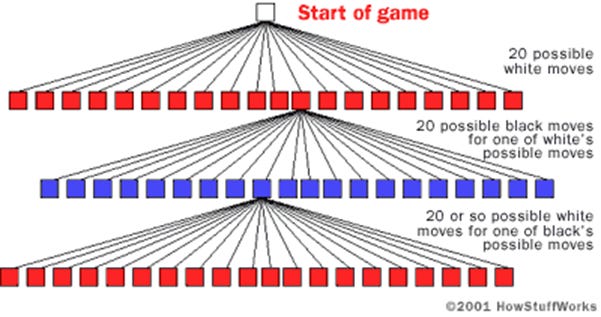

Computers have no understanding of these games: they do not understand the board, or different pieces, much less concepts of play or competition. What they can process are rules, and statistics. Using game theory and mathematics, models are constructed of board positions and the possible moves that can be made, allowing for the next move to be calculated in response to any given board position. As the complexity of these models, the calculation power of computers, and other aspects improve, so too does the perceived chess prowess of machines.

By programming models of possible moves and responses, researchers developed computers that could effectively ‘play’ the game, and throughout the latter half of the twentieth century these computers improved enormously, so that by the 1980s computers were able to effectively play against and beat human players. In 1997, the IBM computer Deep Blue became the first computer to win a game against a then reigning world champion chess grandmaster, making it the most famous chess playing computer in history.

The computer chess problem is fascinating not only from a computer science, AI, or game theory perspective, but has been a subject of great popular interest as well. From the early crowds drawn to the performances of the Mechanical Turk to the widescale publicity around Deep Blue’s exhibition match, chess playing machines operate like a magic trick, seemingly doing the impossible.

Chess, after all, is a game that has specific associations. Chess grandmasters are considered geniuses. Chess is a game played competitively by great thinkers and brilliant minds, and its place in popular culture is enduring, from the popularity of chess championships, the success of shows like The Queen’s Gambit in recent years, or the ubiquity of the chess motif in film, television, etc. all the time to represent logic, opposition, intelligence, and often as a stand in for a more complex conflict unfolding outside the chessboard.

In science fiction, too, there are a number of AI characters that play chess or other games of logic and skill: perhaps most notably is HAL-9000 of 2001: A Space Odyssey who plays chess with his human colleagues, or a chess computer that appears in The Thing. In Iain M. Banks’ novel The Player of Games, artificially intelligent characters play an essential role in a massive game playing tournament that has both political and personal implications. In many of these stories, the concept of computer chess takes on nuanced significance within the story, showcasing not only the intelligence of the machines that play games, but also of the capacities for duplicity, manipulation, and control that come into play in narratives that use chess as a motif.

To see a computer capable of this feat is truly a wonder. It can make them appear truly intelligent, creative, and even human as we try to apply human understanding, emotion, or motivation to the moves they make. It makes sense that the chess problem(and the board game problem, more broadly — even more mathematically challenging games than chess, including Shogi and Go, have only in recent years been successfully played by machines thanks to successful AI programmes like AlphaGo, and as computer power grows, solutions will continue to improve!) has been such an essential one in the artificial intelligence field for so long. Yet when we peek behind the curtain, we see that there is not magic at hand, just human ingenuity, be it the clever tricks of the fake automatons of the past or the complex mathematical work of game theorists that powers chess playing computers to this day.

playing games

Chess and other board based games are not the only ones to be played by AI, and using similar concepts of game theory and rule based models, computers can and have been developed to play a wide variety of games, from poker and other card games to knowledge based games(another IBM developed computer, Watson, became a sensation after it won the television quiz show Jeopardy! in 2011), and even Atari games.5

As the current artificial intelligence boom continues, we should continue to be aware of the games being played by proponents of AI.

How is the promise of AI being used to manipulate the board? What hidden processes are being concealed by the magic tricks performed by AI assistants, AI generated texts/images, and other ‘AI powered’ tools? What human hands are at work behind the marvels and miracles of computers?

For now, I’ll leave you with one more thing: this month’s calendar page(this project has been ongoing since January, and all previous pages have been posted in recent newsletters), illustrated by me and featuring some of my favourite iconic computers and fictional artificial intelligences (including a few chess players!)

Thank you as always for reading! If you enjoy cloudtopia, please consider subscribing, sharing with a friend, or visiting the cloudtopia archives to read more about AI and the other topics I write about in this newsletter.

Coming soon, we’ll get back into discussing museums, revisiting the art of palaeontology, and much much more! I hope you’ll join me then <3

playing the game,

isobel

Much of the AI history and computer science concepts I present here comes from Michael Wooldridge’s book The Road to Conscious Machines, published in 2020 by Pelican Books.

So-called because the automaton was dressed in typical Turkish attire — we don’t have time to get into the orientalist obsession with Ottoman/Turkish things that was happening in the Holy Roman Empire during this period.

Some have claimed that his investigative reporting around this time was what inspired him to write his highly innovative detective short stories.

I am not a mathematician or game theorist, so please excuse the oversimplification of some of the concepts here — there is a TON of actual research in this topic if you are interested in getting into the more detailed and complex explanations of how all of this works!

computers playing computer games… technology gone too far what has society come to etc.