a quick note — cloudtopia is best viewed in a browser, and if you received this as an email you might need to open it elsewhere to read to the end! this week’s newsletter is about writing, digital diaries, and how I record the world. Stick around to the end for the april page of the cloudtopia calendar :)

in February, I went nearly an entire month without writing in my journal, and with every day that passed the burden I felt at the thought of returning to it grew exponentially heavier. Over the last few years, I have written or recorded something in my journal nearly every day, and when life gets busy and I fall behind I feel lost, out of step with passing time and the perhaps too intertwined relationship I’ve developed between my memory of daily life and the way I write its story.

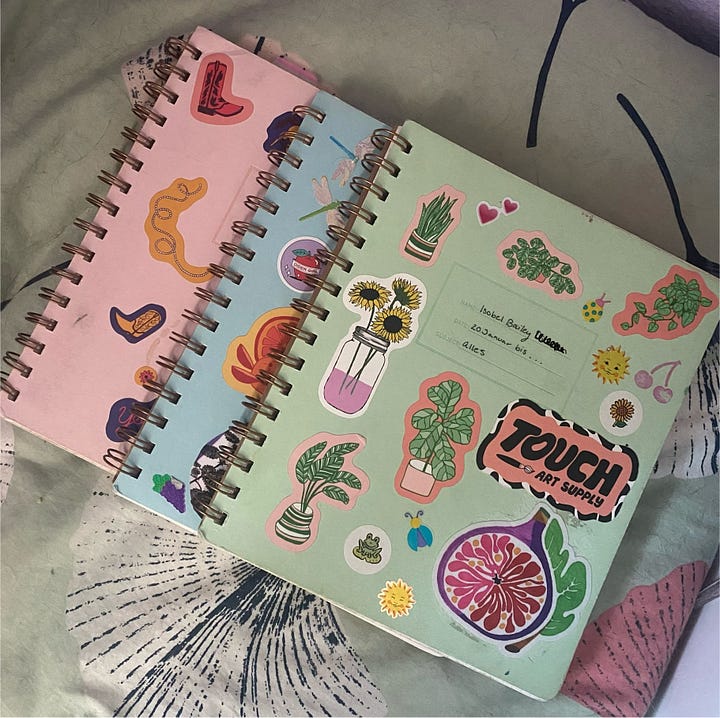

I haven’t always done this - I tried several times in my childhood to start a diary or to get into the habit of journaling and never succeeded, leaving behind diaries that only last for a few pages before getting lost or being turned into sketchbooks or school notes. Journaling in my teen years was reserved for only the strongest emotions or most dramatic occurrences, but as I’ve moved into my twenties I’ve gone through many different phases of journaling, experimenting with style and forms of expression, working through stress and talking through drama, collaging together receipts and stickers and business cards, making lists, and writing overly detailed, obsessive recordings of day to day events.

I set out to write about my love of chronicling my life and the world around me, to understand the need to record every little thing, but in the time I have been thinking about this and trying to write, I’ve realised that it is also about my relationship to technology, both for good and for ill.

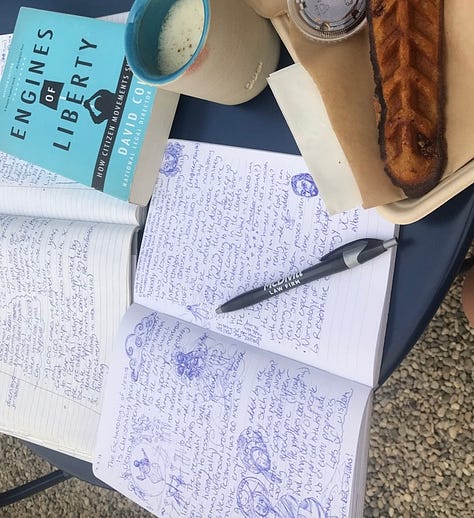

I value keeping up my journal in part because it is a physical, written object. The experience of working on it is tactile and often meditative. I hand write everything in pen, and the sensory experience of this is something altogether different from typing or any other means of recording. The words can flow, events can settle into place, I can organise the chaos of life and the hurry of the everyday into lines in a book. I like that I can take complicated feelings or experiences and make them into a clear narrative that I can refine and order however I choose, that once it is all written down I find that my memories can cohere into the story I tell. In writing it all down, I feel an empowering control over my world.

Sometimes I worry about how much I feel I rely on these processes, worry that the technology critics are right and that my information age, screen-addicted brain is incapable of just encoding memories on my own, that I need to rely so much on my journal, or even more worryingly, my technology, to remember things for me.

These days, my love of recording is apparent not just in my written journals, but in my digital life, which is probably something immediately clear about me just from the fact that I’m writing about this here, for the digital newsletter I run.

Substack is in some ways my most interesting and productive digital diary in terms of the type of thinking I try to do here and the careful curation of different newsletters, from my pop culture essays to my personal updates and travelogues. But it is also the scariest - when I write in my journal, I know1 that no one will read it and that the thoughts I record there are mine alone, which means I can write inelegantly, put down the worst thoughts and the most emotional reactions and the unkind, ungenerous ideas that might otherwise be trapped in my brain. I can be boring and pointless and not feel any guilt about it. But when I write here, I overthink every word and worry more than I would like to about how my ideas will be received — will anyone even read this? What will they think of the work, of me?

But of course, social media-as-diary(and let’s not pretend—at the end of the day, substack, too, is social media) is not the same as a traditional journal, not only because of the added presence of an audience, be it real or imagined.

The sensory experience is completely changed. The writing is different, the reading is different. My words are not shaped here by my handwriting or the pen I write with. My physical notebooks take up space in my house, or are archived away in my childhood bedroom where I cannot read them, they are each unique objects, and should they be lost, the singular words and memories they contain will be gone forever. I think something truly one of a kind is captured in the process of keeping a journal. Even my own memories of the events I write about are not the same as the ones on the page. Yet with my digital diaries(we’ll get into the plurality in a bit!), they can be accessed nearly anywhere in the world through a screen, and endlessly reproduced.

In Re-Enchanting the Earth, theologian Ilia Delio considers the transformative nature of humanity’s current relationship to computer technology and writes about some of the fears that we have about our increasing reliance and entanglement with our digital world, referencing critics like Nicholas Carr(author of “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” among others) who claim that “our minds are being emptied into our hard drives…we are becoming shallow, like pancakes, spread out, flat and thin, across the electronic web.”2

Somewhere amongst the digital wreckage of this web I have many lost journals. There are the long forgotten forum threads and deviantart posts where I began my life online, my deactivated facebook account, my long unused snapchat where the daily activities of my teen years are chronicled, the couple of years worth of almost painfully personal writing I used to share on a private instagram account(this was in the era where we called these finstas), which I have left untouched since.

Delio writes that for many people today, especially members of gen z, “the phone is part of the self, the exoskeletal self connected to the wider world”.3 Parts of myself and my history have been shed, scattered through technology, disconnected and irretrievable.

Recently, in the hopes of bringing down my screentime and fostering a better environment for my research work, I’ve implemented a ‘no videos’ rule for myself a few days a week: no movies, no funny clips that pop up on a social media feed, no youtube, no tiktok, no ‘just one quick episode while I’m eating dinner’ which then turns into the rest of my night. I’ve tried variations of this before — no phone during work time simply does not function when all of my work now requires screentime and digital resources and multi factor authentication to access anything, and bigger goals like ‘no social media’ or ‘no texting’ have proven overwhelming and cumbersome, somehow more distracting than just accepting that the phone is part of my technological exoskeleton. Unexpectedly, though, ‘no videos’ seems to work, and I find myself better able to focus and make reasonable use of technology the longer I practice this habit.

More than any particular rule or controlling my use of specific content, I think what I am really training myself to do with this practice is to think about how and why I’m engaging with my technology. Instead of opening up a social media app to use up time or distract my brain, I have to pause and think about what I’m doing, and about whether or not there is something else I would prefer to be doing with that time. More often than not, turning things like scrolling and content consumption into a conscious decision leads me to make a different choice, like to return to my reading, or even to engage more thoughtfully, like letting myself scroll briefly until I see something that I know is designed to irritate me, which is a signal that it is time to close the app.

In Pandemic! 2: Chronicles of a Time Lost, fellow substack user Slavoj Žižek suggests that many of the social difficulties people faced during the lockdowns of 2020 were not the result of a breakdown of social mores or a lack of socialisation as so many have argued; rather that many of our problems were caused by an excess of social connection.4 Locked away at home and brought together only through the internet, we became eternally logged on. People lost all sense of separation between digital life and a life outside, which left no escape from the social realm. We were always plugged in.

I guess what I’m trying to say is that my relationship with technology isn’t always good, and I find developing ways to better manage it very valuable; but in doing so I also come to realise the fact that it is also essential to living in the world today.

Let’s get off the internet for a second. Since I left twitter, sometimes when I get an idea for a tweet, instead of opening up an app to post, I’ll write it down in a notebook and just let it sit. Generally, I find this is just as satisfying as posting.5

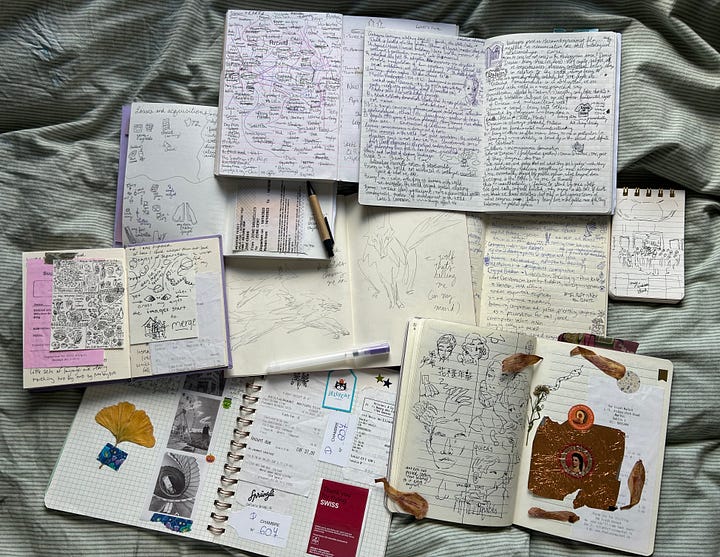

I currently keep five different notebooks/journals. When one of a certain type is filled, I replace it with another, so that many notebooks are always in use at once:

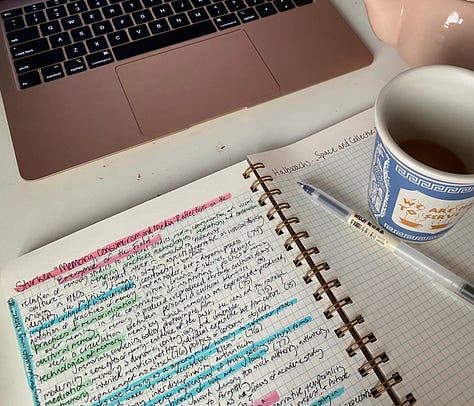

my diary. I write about the events of day to day life here, occasionally force myself to engage with my feelings, paste together receipts and images I gather on my travels and the little tags off tea bags. I prefer a spiral notebook for this purpose, ideally one with grid/graph paper inside, although I also accept lined or unlined. Currently, I use a notebook from my favourite Los Angeles based stationery store, Shorthand,6 which I have been obsessed with since college.

my sketchbook. This is where I draw, make sketches for crafts or projects, doodle while I watch films or tv(this is another strategy I employ to try and stop scrolling). This notebooks must have either unlined or dotted paper. Right now, I use a notebook I got from a visit to Museu Serralves in Porto last year.

my school notes. This is for academic writing, including ideas I jot down for my research work, notes I take in preparation for and during seminars, notes I take at lectures, notes during meetings with researchers and professors. This is a no nonsense notebook.

my reading notes. This one overlaps a bit with the previous notebook, but this notebook is where I take notes while reading books, and while watching films.

my mini notebook. My final category is for anything and everything, but it has to be small and fit in my bag so that I can carry it with me at nearly all times. I find this comes in handy on long train rides, in art museums, and at other unexpected times when you might wish you had a pen and paper — I always do.

Much of my fascination with chronicling is perhaps fine tuned to my own experiences as a person who grew up in the age of the internet with the power and possibility of the digital self.

This obsession with journaling in its many forms isn’t always about the ideas. Some of it is purely a fascination with recording experiences, and this is where online forms of journaling really come into play. There is a broad slate of websites and apps aimed at this desire, and I keep finding more, increasingly specific new platform that allow users to ‘log’ and ‘diary’ the ephemera, art, and experiences of life:

films.

letterboxd is probably my favourite of this genre of website. Sometimes I make myself finish watching a bad film just because I want to be able to log it. Its ‘diary’ feature helps you keep track of when you watched things, and I can trace my film watching history back through a few years of using the app now.

books.

goodreads is the classic app for cataloguing reading habits, although I’ve also been experimenting with Storygraph, and am currently really digging Bookworm, a more recent alternative with a fun social component, and, most importantly, a little worm avatar that you get to design.

music.

There are a multitude of apps that log the music you listen to in order to give recommendations or statistics, the most famous perhaps being Spotify with its curated playlists and annual ‘wrapped’7 but I really enjoy Airbuds, which can be used with spotify, apple music, etc. and which brings together social functionality and newer features to keep you updated on what you listen to most and even allow for new customisation that makes it feel more than ever like a new form of digital diary.

food.

One of my dearest friends recently got me invited to beli, an app which allows users to log and rank restaurants, cafes, and bars they visit, and offers customised stats and ratings based on user activity. I have not yet found its recommendations particularly useful(its database seems to be oriented toward American users) but it is really fun!

scents.

Using fragrantica has helped me to learn about perfumes and fragrances, something that never really interested me until last year when I started building a very humble fragrance collection, and of course, logging the new scents I acquire, try, or wear on certain days to my perfume shelf on the site.

When I first started exploring it out of curiosity, the old fashioned web design aesthetic irritated me, as did the lack of an app version. Now though, I love these things about it and really appreciate the almost nostalgic, 2000s era internet feeling I get when interacting with it. I’ve also experimented with sniff, a fragrance site that has a much more modern app but lacks the comprehensive database and engagement of fragrantica.

birds.

My newest obsession is the Merlin app, a citizen science project run by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology that helps users to identify birds using sound recordings, photos, or observation, and to record their sightings. The intent of this, which I do think is wonderful, is to engage the public in the work of gathering data and recordings, but I find myself treating it like another personal diary where I can keep track of the coolest birds I see and remember the place or time I saw them.

iNaturalist, although not bird specific, is also wonderful for this.

The question this leaves me with is this: are we supposed to know this much about our own activities? Is my digitally extended self spreading too far, becoming too fragmented into these little data points and databases?

For the record, I genuinely enjoy using each of these platforms to record different aspects of my day to day—it helps me to keep track of things, it makes mundane activities feel engaging and can bring value to simple everyday experience. But I also have to wonder if at some point I lose track of what this all is for - do I log the books I read in an app because I love reading, or because I want the easy, gamified satisfaction of marking another book as ‘finished’ and adding to my count?

In a recent two part article for Dirt, Norah Rami wrote about the “State of Gamification” and the proliferation of these apps today:

In the age of big data, much of our lives has been made quantifiable. We can track how long we sleep, how fast we run, how much we read. Individuals today are surrounded by far more information about themselves than ever before—allowing for the emergence of a “quantified self” whose experiences are turned into numbers, which can then be used to assess the value of said experiences.

Returning to Ilia Delio, this concept of gamification and the proliferation of apps that engage our human experience speaks to the big questions facing us about technology and humanity, consciousness and connectivity, and about our entangled evolutions. Citing scholars from futurist Ray Kurzweil to theorist Donna Haraway, Delio considers the ways in which we already are living as cyborgs as we are increasingly enmeshed with the technology in all aspects of life and experience.

“The age of the individual is coming to an end, and the dawn of the Posthuman is on the rise. We are becoming increasingly wired together, and in the not too distant future, our electronically embedded lives will be integrated circuits of seamless connections,”8

As I finally get caught up on writing things down in my journal, I can’t help but return to the weird relationship between experience and how we record it, the story of my life I am telling everyday in so many little forms, from my personal journal to my too-many digital diaries.

In her campus novel The Idiot, Elif Batuman describes the act of journaling so lovingly:

“I washed up, changed into the Dr. Seuss shirt, got in bed, and started writing in my notebook. I kept thinking about the uneven quality of time—the way it was always so empty, and then with no warning came a few days that felt so dense and alive and real that it seemed indisputable that that was what life was, that its real nature had finally been revealed…I wanted to write about it while I could still feel it and see it around me, while the teacups still seemed to be trembling. Suddenly it occurred to me that maybe the point of writing wasn't just to record something past but also to prolong the present, like in One Thousand and One Nights, to stretch out the time until the next thing happened.”9

Across so many handwritten notes and digital recordings, the archive of my past remains stretched and ever present in a way, protected and preserved from the forgetting, destructive march of time, carried forward with me.

Here, again, this push and pull that I still cannot quite make sense of. Am I helping or hindering myself through all this archiving, all this record keeping, this obsession?

In Anne Carson’s “The Glass Essay”, she writes:

You remember too much,

my mother said to me recently.

Why hold onto all that? And I said,

Where can I put it down?10

But in writing, I think she is already answering the question: we put it down in words. Her remembering is woven into the poem, put on the record.

The constant need to record it all that I feel is perhaps foolish, or self absorbed, and maybe it is ultimately pointless, but it is also a process that helps me to make sense of my world and to remember the little moments of life that mean something to me. In weeks where it feels like all of my hours are lost to work and chores and studying and doing the endless dishes that pile up in the sink, I think it means something to write down the little moments that ground me in daily reality and bring light into the mundane. I was stressed all day at work but then I watched a movie I loved, or I saw an interesting bird on my way home, or I got a nice text from a friend, and I find that in writing these little things down, I am reminded that they are real, that they are there, that life is full of little moments of joy and experience. These are the memories that matter.

It sounds corny, and frivolous, and maybe a little too idealistic, but what else is writing in a diary for if not embracing those parts of ourselves?

thank you as always for reading. If you enjoy cloudtopia, why not subscribe, share with a friend, or write a review in your diary and then never show it to anyone?

this reflection has meandered long enough, so I’ll leave you with just one more thing… the april cloudtopia calendar page 🐸 !!!

goodnight diary!

isobel

or at least really hope lol!

in Ilia Delio, Re-Enchanting the Earth: Why AI Needs Religion. Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 2020. ISBN 9781626983823 p. 90-91

Delio, 219.

Slavoj Žižek, Pandemic! 2: Chronicles of a Time Lost. 2021.

Sorry I don’t have a page number I already returned my copy to the LIBRARY.

and gets just as much engagement! lol

I literally never link to brands or shops in my newsletter, but I love shorthand so much I think it deserves a shout. Shorthand pls sponsor me <3

I don’t use Spotify first because it doesn’t have Joanna Newsom’s music and I can’t live without access to Have One On Me or Ys; also I think their new AI features suck, and not just because they are AI, but because their new algorithms are BAD!

Delio, 222.

Elif Batuman, The Idiot. Penguin Press, 2017. No page number again sorry :(

Anne Carson, “The Glass Essay” from Glass, Irony, and God. New Directions Publishing Company, 1995. Accessed on the Poetry Foundation site.