I am trying to become reacquainted with boredom.

Sitting outside on the pavement in front of the hospital A&E entrance, I fight the urge to pull out my phone as I am too accustomed to doing in any situation where boredom seems even possible, lately. Instead, I sit there without scrolling and let the minutes pass by.

I watch people coming and going, a man gets into a row with the security team and is escorted away, then continues to shout from a distance for a long time as the staff members observe uninterestedly. Seagulls squabble over cold chips and takeaway wrappers. Any news feels like an ill omen, most of all no news. I forgot to bring a jacket but for once it does not matter. It is terrifically hot out. The pavement is slightly cold against my crossed legs. In the patch of sky above I watch clouds glide above the rooftops and pass overhead. I keep waiting.

I’ve been trying to do this more, lately. To stop, to wait, to be patient. I try not to look at my phone when I am waiting in a queue, anymore, and I’ve stopped checking social media when I’m on the tram(this started because it makes me motion sick, but I think the damage to my attention span and connection to the world I am moving through is worse), started to accept that it is okay to do chores or take a walk without constant distractions and headphones on. I need to let my mind wander, to daydream, to be able to hear myself think for once. I need to learn again how to be bored, and to wait it out.

It is summer and on bad days and good alike I want to spend it slowly. I want to be bored, to feel the way it felt as a child when I finally ran out of things to do on the break from school, and the days felt never ending. I want the long days of June to ache. I want infinity. I want to sit every day and watch the clouds go by.

I don’t think I am alone in saying that I have forgotten how to wait over the past few years. I’ve forgotten how to be bored. I’m certainly not the first person to write about this, about the diminished attention spans and the increasing expectation that everything in our lives can and should be on demand.

Why think when you can scroll on the internet instead? Why watch a film when you can watch a hundred short form videos? Why take the time for anything when the world is built around immediacy?

Late at night on the longest day of the year I rewatched one of my favourite films, the brilliant Agnès Varda’s 1962 drama Cléo de 5 à 7(Cléo from 5 to 7).

The movie, which is in truth only 90 minutes, takes place in the evening on June 21st, 19601 between five o’clock and seven. During this time, we follow a pop singer named Cléo around Paris as she awaits the results of a biopsy that she fears will show she has cancer. She begins her evening at a tarot card reading where she is warned that illness and change await her — throughout the film we see her interest in superstition and omens recur and feed into her spiralling thoughts about what her test results will show; she frets about wearing a new hat on a Tuesday(apparently this is bad luck) and becomes terrified when a mirror falls on the pavement and shatters. “I'm afraid of everything” she admits, “birds, storms, lifts, needles, and now, this great fear of death.”

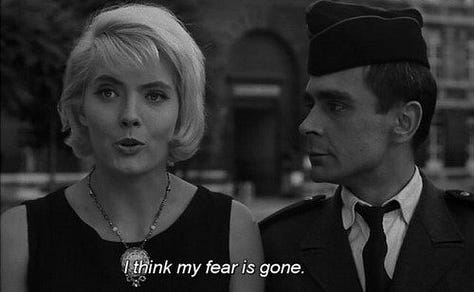

She meets up with various friends and acquaintances who alternate between trying to comfort and distract her from her worries and minimizing her concerns and accusing her of being melodramatic, including her assistant Angele, her mostly absent businessman lover, musicians who visit her to rehearse new songs, a friend working as a model, and finally, a young soldier preparing to leave for duty who she meets by chance in the park. Both awaiting uncertain fates, it is this last meeting that allows Cléo to finally let go of her fears and to find peace in the impermanent present moment.

We have so little time, she tells the man as he walks with her to the hospital, knowing that her test results await and his train will leave later that evening. Then, minutes later, they sit together on a bench in the beautiful gardens of the hospital; would they like to go to a café together? — we have plenty of time.

Time moves in incredible ways in this movie. Occurring mostly in real time, with on screen chapter headings reminding viewers of the precise passage of the minutes, the film progresses often without a clear trajectory or narrative as Cléo stares out the window of a taxi or watches street performances on crowded Parisian boulevards. It could so easily be a dull film to watch, and yet it is mesmerising to watch the minutes pass and to live out the evening of waiting with the protagonist, experiencing her moments of boredom, of delight, of worry and despair alongside her.

Cléo’s perspective is essential to the way the story unfolds and the experience of watching. We are seeing the world through Cléo’s eyes, the image following her train of thought, always moving. We follow her gaze throughout the movie—her view of the streets from a car, or her attention catching on snippets of conversations at the tables of strangers as she moves through a crowded café. As she walks through shops and streets and her eyes find her reflection in windows and mirrors we see her seeing herself, and her inner monologue about beauty and finitude and all her anxieties pours out when she is confronted by her own appearance.

Much of her fear is tied to her sense of identity, the way she is viewed(and specifically, objectified and belittled by men) and moves through the world. “I always think everyone's looking at me, but I only look at myself.” she thinks while looking at her reflection, “It wears me out.” She is called a doll, she is treated like a child when she expresses her worries and frustrations, and she complains that “everybody spoils me, nobody loves me.”

In the scenes where we see her watching herself in the mirror, moments of literal reflection, we see the inner tension between her own sense of vanity and the value she gets from her physical appearance and her success as a singer, which is at odds with her feeling of being neither truly seen or appreciated by the rest of the world. When she thinks to herself while looking at her reflection that “ugliness is a kind of death - as long as I’m beautiful, I’m alive”, she is thinking not only of the sense of self she cultivates through her own looks and her persona as “Cléo”(later, she admits to Antoine the soldier that her name is really Florence), but the underlying terror of finitude and mortality, that she is thinking not just about her beauty or how she is being seen, but about the very real possibility of a cancer diagnosis that awaits her.

Where Cléo looks, we look. The images or sounds or ideas that get her attention become, however briefly, our focus too, with lines of overheard conversations and her own despairing thoughts, full of insecurity and superstition, blending seamlessly into the film’s soundscape of melodramatic score and mundane daily life. In one scene, Cléo’s composer and lyricist(the composer, Bob, is played by the film’s actual composer Michel Legrand, who has come up a lot in my newsletters!) arrive at her apartment to visit her, and they try to cheer her up and encourage her to rehearse new songs, although she is despondent and distracted. As she gets swept up in the music, the camera begins to move more playfully throughout the room, swinging from side to side in time with the music and the movement of the swinging chair where she sits in her massive, frivolously decorated apartment, full of wandering cats and necklaces hung around the room like amulets. The light hearted silliness of the scene here shifts when she begins to sing a more emotional ballad, and her feelings overwhelm the scene and our view of it, the rest of the room fading away to black so that only her tearful face remains as she sings directly to the camera—”gnawed away by despair… without you, without you.”

Cléo is dramatic and superstitious and over the top, certainly, but the depth of emotion and inner turmoil that is unleashed in this scene feels very real and reminds us of the complex concerns that hide under the surface of her silly obsessions with pop music or what hat she should wear.

Later, Cléo spends time with artist friends and they watch a silent short film together, assuring her that laughter is the best medicine for whatever ails her. The film is absurd and silly; a man and woman say goodbye to one another on Pont MacDonald, and when he dons a pair of sunglasses, a dark, tragic scene plays out through his tinted vision of his fiancée being killed in an accident; yet when he takes the glasses off, he sees the scene play out again, this time with a happy ending as he is able to see the light again, and the two reunite. This scene is a nice interlude and makes for a fun homage to both silent film and to Varda’s french new wave contemporaries, including Jean Luc Godard and Anna Karina who appear in it; more importantly it also points us back to the idea of perspective and the way our view of the world is shaped by perception. The man’s view of Pont MacDonald in the short film is warped by his darkened vision; Cléo’s experience of Paris, her view of herself and others, is driven by her spiralling anxieties and creeping dread, until at last she is able to change her perspective.

When she walks in the park and meets Antoine, he makes an effort to see her for who she is: not as melomaniac2 Cléo, but as Florence, a woman awaiting change on the first day of summer. As he, too, lives through a day of expectation and anxiety before his impending departure from France, the two meet in a common place of uncertainty and finitude. Even with the knowledge that the time they can spend together is short, they are able to truly see one another and be present together.

“I’m sorry I’m leaving. I’d like to be with you,” he admits after they meet with her doctor, and she reassures him, grounded finally in the present moment, that he is.

“I think my fear is gone,” Cléo says at last, “I think I’m happy.”

I try not to let the superstitious part of my brain take the reigns, but there is no denying that the world is scary. I understand Cléo’s terror of ill health, of ugliness, of omens and broken glass. Perhaps most of all, her fear of openness..

In times like these, I often find myself following a path much like Cléo’s. People watching, playing music, wandering in the park, watching a film — little things that can change the texture of life. On the bus with Antoine, Cléo remarks that “today, everything amazes me, the people’s faces next to mine,” and I often find this is true in mundane moments. Facing fear, finding new ways of seeing. Everything becomes incredible. I remember several years ago being released from hospital and thinking on the bus ride home that the sunlight had never been more beautiful; waking up the next morning and feeling like it was the first day of my life. This is my first day on planet earth, I told myself, and everything felt different and new.

I think boredom, too, is shaped by our perception, and I’m learning to love it the more I make an effort to find time each day to sit quietly and let time pass. In a world of immediacy and constant information being scrolled into our brains, boredom can feel unbearable. Stillness is unacceptable, and openness to the world and to experience becomes terrifying.

So I let myself get bored on my break at work. I stare out the window on the tram ride. I take the dog for a walk, and let her stop to sniff the grass, and let my phone get lost at the bottom of my bag. We pause for a long time to watch bumblebees hard at work in the flower beds. We watch the clouds move languidly through the summer air. It doesn’t matter how long it takes. The time will pass anyway.

This week I’ve been reading Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf, a novel set in London after the great war which takes place across one day in June. Not unlike the camera following Cléo’s train of thought in Varda’s film, Woolf wrote this novel in a stream of consciousness style, and it has a beautifully flowing, contemplative style, perfectly suited to a long summer day and letting your mind wander in the park.

Last June, I wrote “in bloom” a newsletter about three more stories that take place (mostly) on a single day in June(specifically the 16th); each is set several decades and an ocean apart from Ireland to Vienna to Michigan, and each contemplates the interplay of life, death, infinity, and finitude that occurs on long summer days. You can catch up on that here:

in bloom

The beautiful summery days and bright sun of may in Dublin have passed, and we find ourselves now in the gloomy period of june. We’re approaching the midpoint of summer, so it’s light all the time, the sun waking me up hours before my alarm and stretching the afternoon far into the night. This is the time of year when nature stops making sense.

Thank you so much for reading. June is nearly over, but I will leave you for now with one more thing: the July calendar page of my cloudtopia calendar! Much like Cléo’s weird apartment in Cléo from 5 to 7, this one is absolutely full of cats, and in particular compiles a lot of the portraits and sketches I’ve been doing in the last few months or so of my beloved childhood cats, a baby cat who turned 1 year old this month(everyone please say Happy Birthday Beatrice!) cats I meet in my neighbourhood, and some other familiar characters. Enjoy :-)

watching the clouds,

isobel

This is my best guess for the date on which the film is set — we learn from Antoine that it is the longest day of the year and the first day of summer, indicating that it is 21st June, and that date fell on a Tuesday in 1960.

In the film Cléo is teased for being a maniac for melodrama, which is turned into the French portmanteau melomaniaque. In English, melomaniac refers to a person with an excessive love of music. I think both definitions kind of work in this case in terms of how her character is viewed by the people around her!