The beautiful summery days and bright sun of may in Dublin have passed, and we find ourselves now in the gloomy period of june. We’re approaching the midpoint of summer, so it’s light all the time, the sun waking me up hours before my alarm and stretching the afternoon far into the night. This is the time of year when nature stops making sense.

Also fast approaching is the 16th of June, a local holiday called Bloomsday, named after Leopold Bloom, the main character of James Joyce’s almost absurdly controversial novel Ulysses. Set entirely in Dublin and covering over seven hundred pages, the story takes place all within the span of a day—16th June, 1904. The date itself was chosen by the author because of its significance to him and his wife, and now over a century later, people around the city celebrate the anniversary with literary readings, special tours, live music, meals, and plenty more inspired by the events of the 16th as they occur in the book. Mostly, it’s an excuse for tourists and Dubliners alike to wear big hats, go to pubs, and pretend that they’ve read Joyce. I find it all very weird and immensely charming.

Say what you will about Ulysses(there’s a lot to say and I’m sure some have already stopped reading at its first mention), but there’s something really magical about the enduring legacy of this text and the psychic and tangible effects it has had on the landscape of the city its author once called home. This is a book that was controversial when it was being written, when it was published, and has remained controversial basically every day since. It regularly gets singled out as one of the best novels ever written, as well as one of the most hated. The text itself follows a massive array of themes and ideas, covers a multitude of literary styles, explores with incredible detail broad areas of the city of Dublin, engages deeply with emotion and experience and humanity—yet ultimately, it is the story about 16th June, one day in a life.

That little contradiction, the combination of immenseness and specificity, generates something wonderful and timeless in the text, as well as in the communities and inspired works that have arisen from it. Life, in its greatest and tiniest moments, is what we’re thinking about this june.

A key text and source of inspiration for Ulysses is The Odyssey—Joyce took the Latin version of the hero Odysseus’ name as the title of his novel—and much of its character archetypes, story and chapter structures, and other elements are taken from the Homeric epic.

In Nostalgia: When Are We Ever at Home?, philosopher Barbara Cassin writes about the Odyssey and the imaginary of temporal experience in the text.1 Odysseus’ journey home from war takes him ten years, a decade where time passes unevenly, with months or years spent on new shores before the journey is utterly changed by mere moments. All the while, he works towards returning home to his own country, and to his wife Penelope who spends years faithfully waiting, and his son Telemachus who almost traitorously has grown from a child into a man in his father’s absence. When he returns at last he ends his adventure in his own bed, which he carved himself into a tree rooted in the soil of the island of Ithaca, a profound symbol of his homecoming and all that it means.

As Cassin notes, however, Odysseus’ reward for surviving the seas and reclaiming his place in his rooted home is not the return he yearns for; instead he is fated to be sent off on another quest, one he will never again return home from. He is given one night to return to his root and to reunite with his wife and his home and himself, the identity and personhood that he can only reclaim when he has returned to his place—and then to return to the wandering of his life. Yet even after a decade of waiting and wandering, the night of nostos—return, the root found in words like nostalgia—is an incredible expanse.

The threshold of this moment in the story, Cassin argues, is essential:

“The infinite is here in the finite, a perfect description of love.”2

In the 1995 film Before Sunrise, Jesse(Ethan Hawke) and Céline(Julie Delpy) meet as strangers on a train. In the morning, Jesse will fly home to America, and Céline will continue to her intended destination of Paris, but until then the two spend a spontaneous day together in Vienna, getting to know one another more deeply as the night goes on. It is 16th June, 1994.

The bond the characters develop in the short span of time during which they are together has made this film a beloved, timeless romance for many viewers, and it is exactly the sense of infinite time and possibility that the two are able to find in their brief time that makes the story so magical. At the end of the story, the two part ways, with the promise to meet again. The sun must come up, they have to continue on. We don’t know whether they’ll find one another again, if they’ll have a future, or whether this is it3, but there is an endless, beautiful love shared in this moment, no matter what might come.

The final chapter of Ulysses, “Penelope” is written as an internal monologue, essentially a long run on sentence, as Molly Bloom lays in bed in the early hours of the morning thinking, and recalling her past relationships and experiences. In a schema he created as a map to the puzzles and ideas in the text, Joyce did not assign this chapter a specific hour of the day the way he did others, instead writing a symbol: ∞

There is an infinity of time in the wee hours of the morning. Infinite possibility, with the end result of the chapter and the novel in total being perhaps its most famous moment: a final declaration of “Yes.”

The sun will rise in Dublin at 4:56 in the morning. People will wake up early to visit the Martello Tower in Sandycove where, in the 1904 of the novel, Stephen Daedalus and his companions begin their day, or they’ll visit the Eccles Street of Leopold Bloom’s home, which is today a surgeon’s office. Like ghosts, we’ll be retreading the paths of a past version of the city which doesn’t quite exist anymore. Ever and never changing, Dublin on 16th June comes again, endless and expansive and turning its face to say yes to the sun before it sets late that night, then rises again.

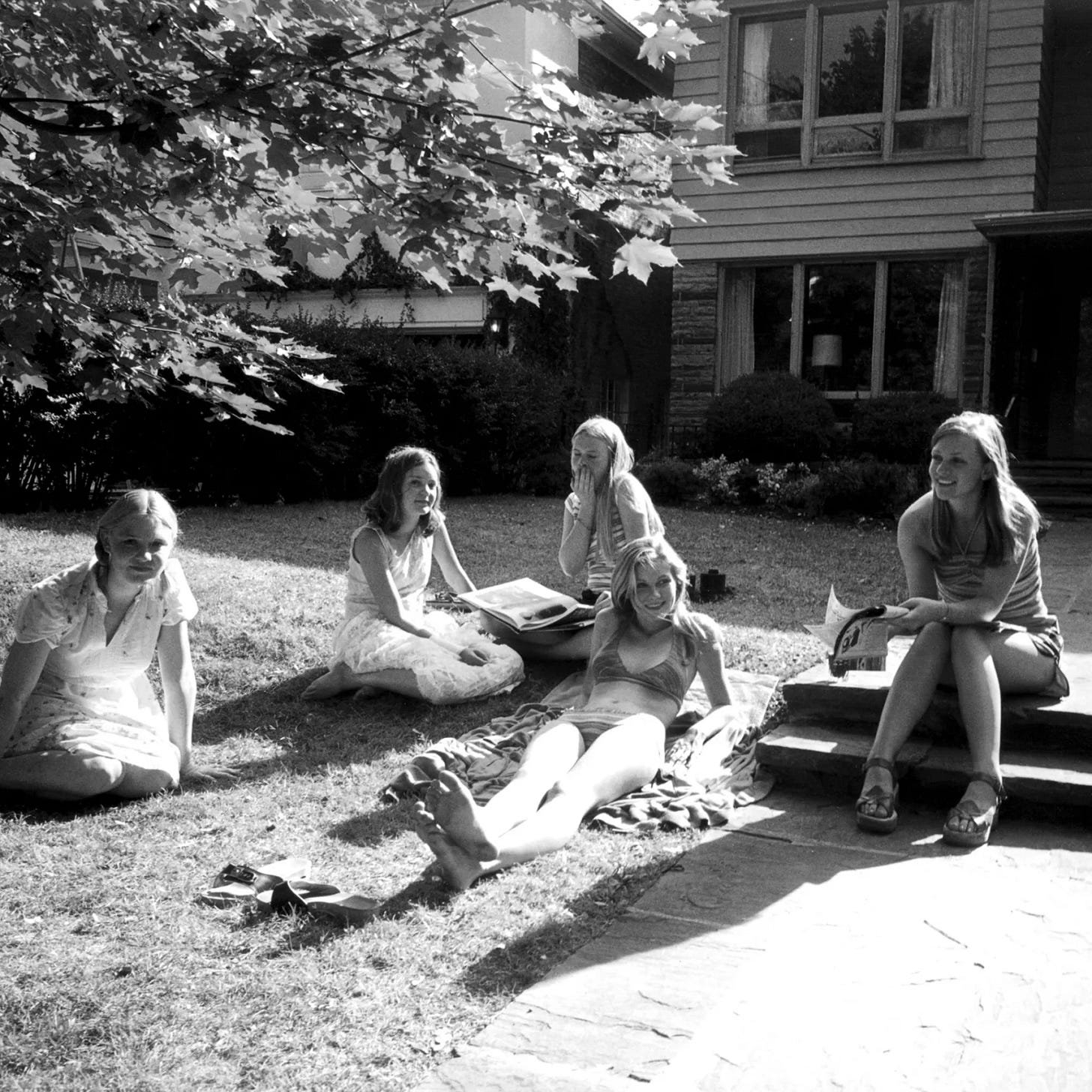

Jeffrey Eugenides’ debut novel, The Virgin Suicides sees the lives and deaths of five teenaged sisters in suburban Michigan. It is an expansive story, narrated by the chorusing voices of a group of boys who try to make sense of the events from their idealistic, distant viewpoint of the girls. The story begins and ends with the 16th of June.

In an interview with the Paris Review, Eugenides describes reading A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Joyce’s predecessor to Ulysses, as a student, and the profound impact the work had on him and his interest in becoming a writer.4 It can be no coincidence that the date Joyce selected for his rambling epic is also the date Eugenides picks for his tragic teens’ suicides.

The novel, dreamlike, takes place in an almost mythic time, its haunting narrative seeming to stretch endlessly across the short year that it primarily describes, throughout which the Lisbon girls are simultaneously alive, through the events of the story and in the way they are remembered by the narrators, yet knowing as we do that they are doomed, they are always already dead.

From “James Joyce”5, a 1969 poem written by Jorge Luis Borges:

In one day of mankind are all the days of time…

The story of the world is told from dawn to darkness

thanks for reading. i hope you are having a lovely june and that the days are long and full of yeses!

in finite ly yours,

isobel

Cassin, Barbara, and Pascale-Anne Brault. Nostalgia: When Are We Ever at Home? Fordham University Press, 2016. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt19rm9jg.

Cassin, 21.

Ignore the fact that they made two sequels to this with me for a second, please

James Gibbons (Winter 2011). "Jeffrey Eugenides, The Art of Fiction No. 215". Paris Review. Winter 2011 (199).

Borges, Jorge Luis. Selected Poems, edited by Alexander Coleman, New York: Viking, 1999, 273. Translation by Stephen Kessler

loved reading this!