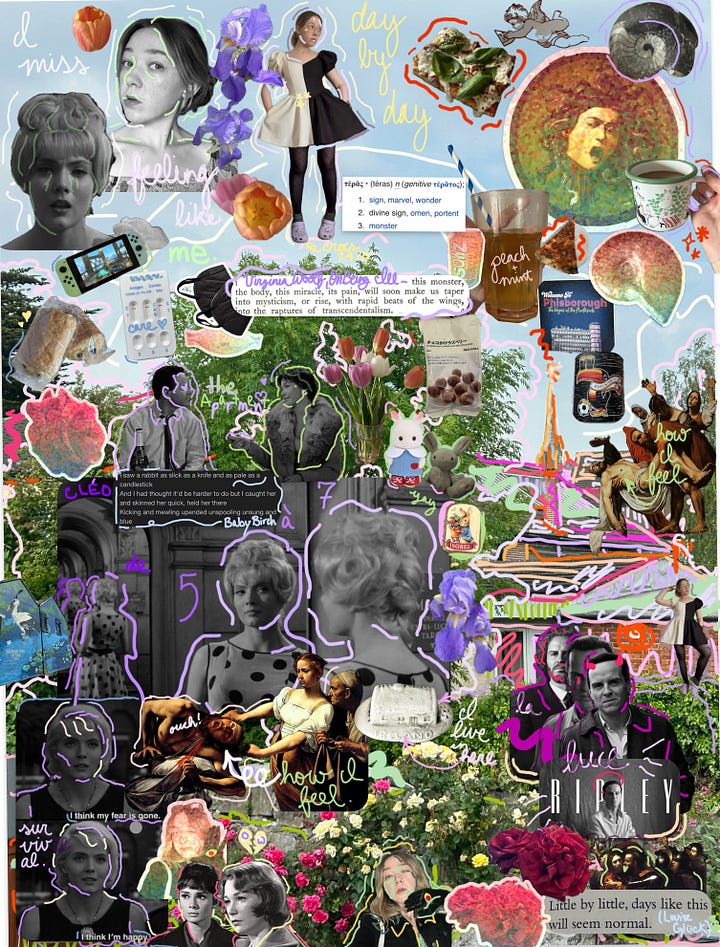

A few weeks later, and I still don’t feel quite like myself, but I’m getting nearer.

It doesn’t seem quite right to measure recovery time in ‘weeks’ or even ‘days’, except to document the time off I am granted from work, or to count the number of pills I have to take.

Instead, time lately is measured in bruises. The shifting colours of the back of my hand become a calendar: the fresh, violent fuchsia of the days when I can barely sit up in bed, cannot stand on my own, and later, the greens and blues of mornings sitting very still in the garden and slow days of rest, and then, eventually, as I return to life, the bruise has faded to a dusty purple, appearing sometimes like a smudge of dirt, or others like the shadowy dusk skies that emerge at the end of a long day.

I am better—still getting better—but I am exhausted. I want to be well.

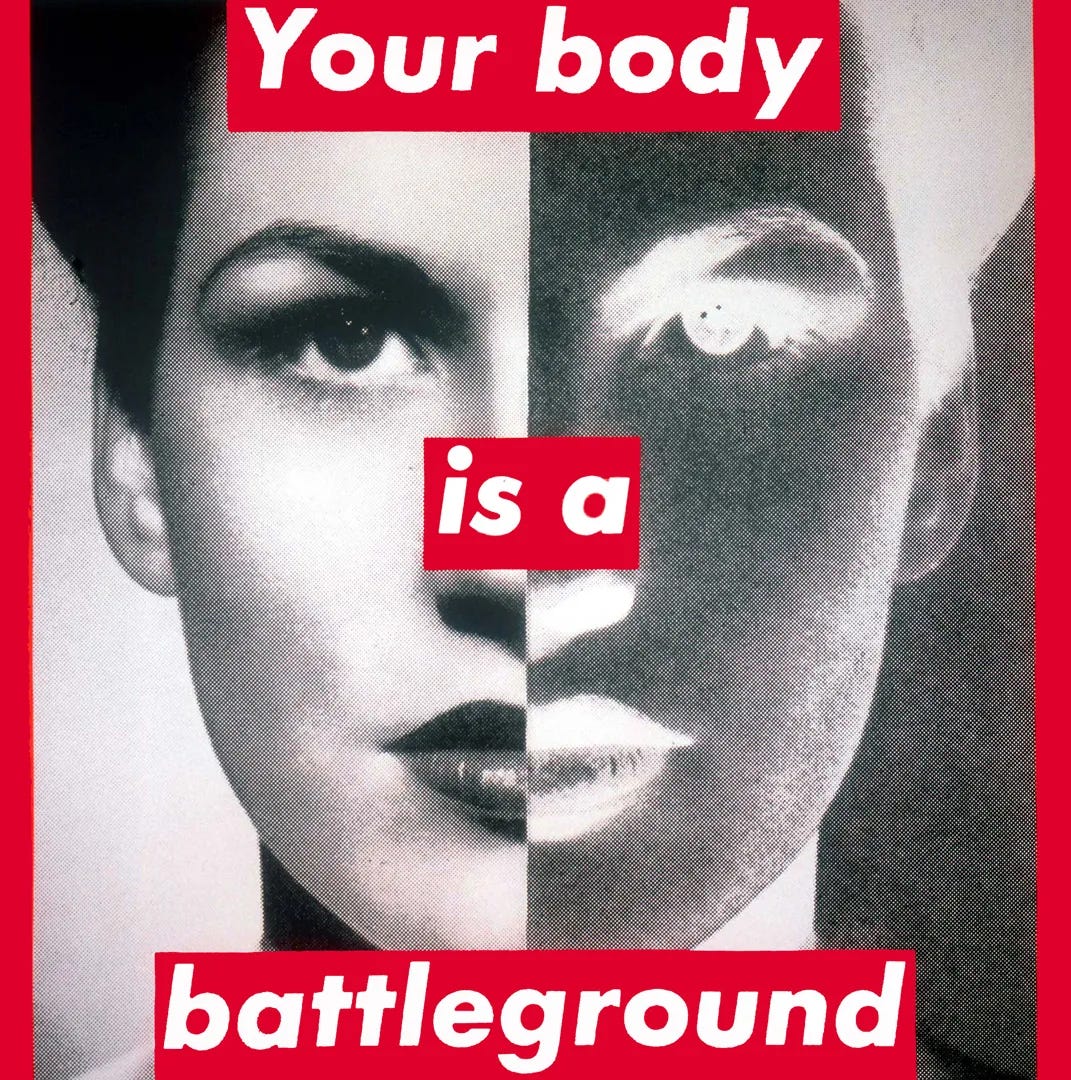

I don’t want to be on the battleground any more.

I first saw Barbara Kruger’s “Your Body is a Battleground” in person on a miserably hot day, the summer I was 20 and living in Los Angeles and feeling unwell all the time, but disguising the poor care I was taking of myself by pretending to be carefree and thrifty and ‘living my best life’. I was in an era of personal turbulence. I pushed myself too hard for weeks on end. It was a saturday morning and I hadn’t slept enough, hadn’t eaten, walked an hour to take the metro downtown and then walked again up the steep hill to the Broad Museum, waited in the long queue to get inside in the 90 degree heat, and by the time I entered the gallery, I was dizzy and almost too weak to stand, dark spots dancing in my vision. I found a bench and tried to breathe, surrounded by art and not even able to see it, and sat very still until I managed not to pass out.

And as I came back to myself in the air conditioned cool of the gallery, I was staring into the haunting eyes of this image, like her message was being broadcast directly to me:

“Your Body is a Battleground!”

The stark black and white of the image alongside Kruger’s signature bold, blood red text in this piece make for an iconic work that has become an emblem of feminist struggle. Most often, it is discussed and analysed in connection with the fight for reproductive justice. But for me, the work is a profound expression of many of my own experiences with chronic illness and mental health, and I have always connected it to this moment, a point in my life where I suddenly and consciously realised that I had been at war with my body and its needs, and that I needed to try and end it. Since then, it comes back to me like a mantra or a warning or some kind of divine sign amidst the cycles of illness and hospitalisations and treatments and flare ups and rest. The battle wages on.

I struggle, still, with ‘resting’. I like movement and routine and feeling like I’m doing things. I struggle with taking care of myself, with nourishing the body, with the patience and gentleness that we must learn to show to ourselves in order to be well.

After my surgery, I spend weeks resting, at first because I cannot do anything else, and then because I make the conscious effort to do so.

For a while, I stayed with friends who generously offered to look after me and feed me and ensure I was okay. They brought me meals and cups of tea through the days and I tried to let go of the guilt of not helping, not doing things, and just being. In their pink house, I half paid attention to the shows we watched, soothed by the familiar rhythms of laugh tracks on old sitcoms, or I laid in bed watching the street outside my window, passersby, cars, dogs, horses, and, on one memorable evening, crowds making their way to a football match draped in keffiyehs and Palestinian flags; all night music and chants carried on the air through open windows.

Time passed slowly, dreamlike. I am uncomfortable with stillness, unaccustomed to being in a state that feels like nothing more than unproductiveness. But there was nothing to do but rest, so I rested. Slowly, the dreamy fog of all-consuming pain and exhaustion dissipated, and I was strong enough to sit in the sun and listen to birds. Soon, it wasn’t excruciating to laugh, so I laughed more and more. I learned how to play super smash brothers and was really bad at it! I took showers and ate food and wore trousers again and enjoyed the little human luxuries.

It’s hard to talk about the battles of the body. They are at times too horrific, too gruesome, too personal to lay bare; or they are the stories of rest and of sleep, stories where nothing happens.

In “On Being Ill”1, Virginia Woolf writes about the problem of illness as a literary topic:

Consider how common illness is, how tremendous the spiritual change that it brings, how astonishing, when the lights of health go down, the undiscovered countries that are then disclosed, what wastes and deserts of the soul a slight attack of influenza brings to view, what precipices and lawns sprinkled with bright flowers a little rise of temperature reveals, what ancient and obdurate oaks are uprooted in us by the act of sickness… when we think of this, as we are so frequently forced to think of it, it becomes strange indeed that illness has not taken its place with love and battle and jealousy among the prime themes of literature.2

Illness and wellness are profound forces within human experience, and yet the experiences of being ill(and this is especially heightened for the chronically ill and disabled) are relegated and deemed unworthy of epic tales or literary reckoning. In spite of the depth of experience that they bring, Woolf notes that stories about illness would be considered boring and plotless by readers; but simultaneously that “those great wars which [the body] wages by itself” might simply be too terrible to bear, and that we do not have the courage nor the framework to make sense of them.3

“this monster, the body, this miracle, its pain, will soon make us taper into mysticism, or rise, with rapid beats of the wings, into the raptures of transcendentalism.”4

One of the ways I often find myself tracing the story of illness is through etymology. I find something strangely comforting(and terrible) about the way that so much of our medical terminology can be parsed into its ancient roots, that people have been experiencing and trying to describe the same pain and suffering with these words for so long. A mythic story is unravelled, for example, in the word τέρας, an ancient greek root which appears in terms such as teratology and teratoma and teratogen, which in medical contexts are used to describe abnormal growth. But the original root has the following meanings:5

sign, marvel, wonder

divine sign, omen, portent

monster

At the root of pain and illness, we find the monstrous and the divine at once(“this monster, this body, this miracle, its pain,” as Woolf describes it). There is something profound in the dualities of the body, the place that in health is our home and in sickness becomes a frightening unknown; its language reflects the imagery of ancient myths, of demigods and hybrid beasts, the catastrophe of the mundane meeting the deified.

The pain and suffering of the body is, as Woolf suggests, a literature-worthy story of passion and drama. In the long days of being unwell are mythological epics that stand alongside Theseus’ navigation of the Labyrinth, or Beowulf’s battles against Grendel and the monster’s mother. We unravel blood curdling tales of suspense and body horror to rival any horror film. And, of course, it’s a story of medical science, of politics and justice, of life; endless stories.

I still can’t reconcile the parts that are too dull, or too disgusting, the things I don’t say because I know that no one wants to hear them, the terror, the melodrama, the pretention and reflection of trying to talk about all of this—but still, I keep trying.

The battle is never over. Even as I’m still recovering from this front, I can’t help but think about the fact that the relationship we have with the body—with our bodies—is for life.

For me, chronic autoimmune illness means that my body is too often at war with itself, my overactive immune system taking the offensive against my own cells and organs and seeking destruction. This war may never truly end. Its scary, and unpredictable, and exhausting. I’m in a better place now, with good supports and treatments, but for months and years my experience of struggling with illness was all encompassing, and even now it is hard to feel safe and at home in my body.

This is all we get. There is nowhere else to go, no other story to tell.

On the days when I could do little more than lie very still, I kept thinking about how unbelievably lucky I was.

I was miserable, yes, but I had a bed to lie in, and care, and medicine for the pain, and the incredible privilege of stillness. Dozens of hospitals and medical facilities have been destroyed in Gaza, where thousands are injured, in pain, disabled, ill, and displaced without any of the treatments or care they need, the privileges that allow me to barely get through my day.

In this way too, stories of the body and illness are integral to human experience amidst the horrors of war and genocide. The battle and the body are inseparable.

Take a moment and visit Operation Olive Branch, and please donate as you can to their mutual and direct aid campaigns to help people in need of support in Palestine.

Thank you for reading cloudtopia, and for your patience with some of the schedule changes to this newsletter — I’m going to be a little less strict with myself about publishing weekly, moving forward, so the publishing schedule might continue to change so I can prioritise rest(and also, just regular life things!)

I hope you’re giving yourself some of the same space and gentleness. I hope you’re well. If you like this newsletter, I’d love for you to subscribe, get in touch, or maybe tell a friend, a nemesis, a colleague you tolerate during your awkward small talk during work, etc :-)

with care and solidarity,

isobel

Woolf, 33.

32.

32.