dear reader,

welcome to cloudtopia! in this week’s letter, you’ll find enclosed musings on phenomonology, clocks, a visit to Geneva, books with the word ‘time’ in the title, and the history of watches…

time

In my first lecture as a newly minted PhD candidate—I still find this fact hard to believe— our professor skips past introductions or syllabi and dives straight into the topic of phenomenology. We talk about intention, perception, presence and absence, noesis and noema, and most of all what it is to live temporal existences. It is one thing to measure time objectively, time as it appears on a clock, time through the passage of days, but another entirely, as Edmund Husserl writes, to “undertake an analysis of pure subjective time consciousness—the phenomenological content of lived experiences of time”. We talk about memory, sensation, love, boredom, all the things that complicate and entangle our lived time. The clock ticks away and before we know it the temporal nexus of the first class has ended.

In the next few classes we’ll be studying the monumental(and yes, controversial) Being and Time, exploring further the issues of phenomena and temporal experience, and I can feel my brain kicking into gear as each day, waiting for the bus or watching the hours pass during long afternoons in my office, I think about all the new phenomenological concepts already crowding into my head, about being and being-in-the-world, about time and finitude. I like that the english title “Being and Time” can easily be spoken aloud as1 being in time; a way to think about what it is to be a finite being, to exist within and through temporality. I like the way that these words side by side call to mind phrases like “the time being” — which is to say an intangible, unspecified, yet present and enduring period of time— but which can be given dual meaning, as by novelist(and zen Buddhist priest) Ruth Ozeki in A Tale for the Time Being, to mean an existence with temporal dimensions and limitations:

“A time being is someone who lives in time, and that means you, and me, and every one of us who is, or was, or ever will be.”

As my train of thought spiral off track, I’m thinking too about quantifiable time, of Marcel Proust’s interest in train time tables and his assertion in In Search of Lost Time that the development of railways and the urgency of train departure times “has taught us to take account of minutes,” our perceptions of time itself changing to reflect a more hurried world.2 While we might call the time on a clock ‘objective’, we didn’t always have timely trains, or standard time zones, or clocks on which we could rely.3 Even the way that our capacity for ‘objectivity’ and ‘measurement’ in how we think about time will always be contextual and connected to our experience of time as a phenomena, and to the feeling of living — of being— in time.

being

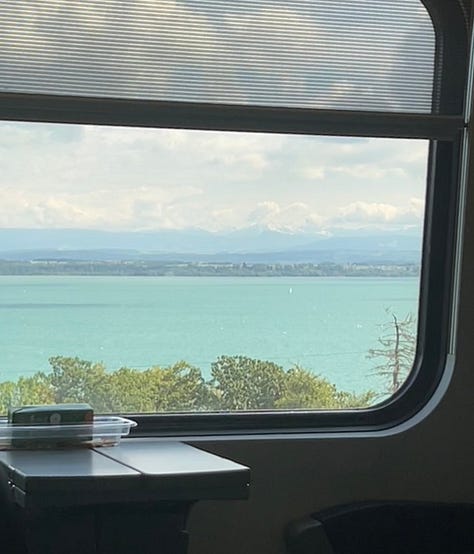

I spend saturday afternoon on a train in the Alps. We cross rushing rivers and pass lush forests, fields of heavy, drooping late season sunflowers and still growing, bright orange pumpkins. As we approach Neuchâtel, the windows on one side of the train are eclipsed by the silvery waters of the lake, while on the other side lush vineyards and little houses with painted shutters climb steep vertical slopes. Somewhere on this lake, I learn from road signs and train platforms, is a village called Grandson, which strikes me as bizarre and delightful.

In the Alps, I am always overtaken by a strange homesickness—or perhaps more aptly, Heimweh. It feels right somehow that ‘nostalgia’, a term constructed from the ancient greek roots ‘return’ and ‘pain’, was invented by the Swiss.4 I grew up in the Rocky Mountains, which are nothing like the European Alps, really, except in all the ways in which they are exactly the same; and being surrounded again by mountains is simultaneously aching and exhilarating.

In Switzerland, I once again finding myself thinking far too much about time. It’s not just the extremely punctual trains and trams I take on my trip across the country, or the PDFs of readings for class I’ve downloaded for the long journey but do not actually look at once. It might be the obsession over watches, and the ubiquitious advertisements and images of clocks on wrists—no matter where I look, I can’t seem to escape the time being.

watches

The city of Geneva purports itself to be the birthplace of the watch as a timekeeping device, a claim that made me say “well that can’t possibly be true”, and so to wikipedia I hastened to find a very useful “history of watches” and a further “history of timekeeping devices”, which taught me a lot while distracting me from my original question: who invented these things? In these histories, we see the development of various timekeeping instruments; neolithic monuments as astronomical calendars, sundials, clocks derived from the burning of incense or candles, astrolabes. The contraptions get more complicated, the mathematics become more advanced, the clocks become more sophisticated, and by the 16th century we’re seeing portable, wearable devices called ‘watches’5, first as pendants, then on chains to be kept in pockets, then on the wrist.

Did you know that wristwatches were considered to be women’s watches for several hundred years, and only became seen as a masculine accessory after the first world war, when new military tactics necessitating precise synchronisation required soldiers to wear them? Did you know that in the 1960s special watches were developed for use both in outer space and undersea by explorers? Did you know that you could go and buy a new 2024 Patek Phillippe wristwatch6 for the incredible price of just under €300,000 today, and it will never be as cool as a children’s wrist watch from the 1970s with Snoopy on it?

It is true that Swiss inventors, mathematicians, and businesses contributed key developments to the history of watchmaking, and that a Swiss company held the first trademark on watches, as well as that today many of the world’s most well known and expensive watchmakers are based in Switzerland. Geneva’s tourist information ties its history of watchmaking back to the 16th century and to its next most annoying cultural export, Calvinism:

“The story goes that Calvin decided to ban the wearing of jewellery during this particularly austere period and that the city’s goldsmiths had to find an alternative and turned to watchmaking, delicately decorating watches and clocks with precious stones and materials. Thus was born in the city of Geneva, the luxury watchmaking industry and its unique pieces.”7

Jean Calvin8 is an important figure in Geneva’s history, a theologian and reformer responsible for establishing his reformed ministry(and according to some historians, theocracy) in Geneva, and for gems like this:

"All are not created on equal terms, but some are preordained to eternal life, others to eternal damnation; and, accordingly, as each has been created for one or other of these ends, we say that he has been predestinated to life or to death."

Yikes!

Calvin was really into lots of boring Protestant reform stuff like repentance and the importance of hard work for redemption and God’s grace. He wrote that he did not wish to become seen as an idol of the Reformation(so of course there are loads of statues and streets named after him), he spoke against the Catholic Church and what he perceived as the sinful idolatry of depictions of God in Catholic art, he condemned the “perpetual idol factory” of “the human heart”.9 I wonder what he would think of Geneva today and its skyline littered with the names of major watchmakers and banking firms, of the nouveau riche tourists, of the bankers, businessmen, and believers who toil for divine redemption in the form of false idols, luxury watches and designer brands.

clocks

Recently I saw a post10 that talked about owning a clock being an important milestone of adulthood, and the comments were full of people we can presumably term ‘young adults’ lamenting that they do not and perhaps have never owned clocks, and despite being so innocuous and bizarre this stopped me in my tracks and made me say “hmm I don’t own a clock. Am I even an adult?” At the flea market that weekend we came across a collection of vintage table clocks and I mentioned this to my friends who all agreed, no, they didn’t own clocks either, and that it would feel very strange to bring one into our homes today, our homes filled with smart devices and digital clocks built in to everything. Maybe we just don’t need physical, analogue timepieces anymore? I mean, does anybody still own a clock? Where once the development of timekeeping instruments would have been a valuable innovation, and the wearing of a well-made watch would be indicative of industriousness in a society that prized and revered order and precision, what meaning—beyond signifying wealth—remains today in a time where clocks and watches and all those things that were developed over centuries have become so sophisticated and reliable that they are nearly forgotten and obsolete? I wonder how the ‘objective’ version of time we get from clocks is changing with technology, and how our own perceptions and experiences of time as phenomena might be changing too as not just the technological capabilities of watches have developed, but so have their ideological ties to political and religious values, and capitalist pursuits?

But for now, my Snoopy watch is reminding me that it is time for me to schedule this newsletter and return to my reading for next week’s class. For the time being, that’s enough thinking about clocks.

I’ll leave you with one more thing, Michel Legrand’s “Watch What Happens”11 which I listened to a lot on my trip and which inspired this week’s title.

thank you for reading! i hope you enjoyed the strange ramblings of this week as i find myself in the midst of a lot of things and the start of the semester. coming soon, I’ll be sharing some new reflections from art museums I’ve visited recently, returning to the work of Arthur Conan Doyle for the next edition of my ‘the strand’ series(this will be about one of the best ever Holmes stories!), and plenty more. i’d love it if you would subscribe, share with a friend, or get in touch.

until next time :-)

isobel

Kind of like that thing where people used to mishear/misremember the title as Sex in the City. lol.

Henry Grabar, “The Lost Excitement, Pathos, and Beauty of the Railroad Timetable”, The Atlantic, November 2013.

Ephrat Livni, “How train travel put the world on the clock” Quartz, May 2018.

Other great inventions from Switzerland: watches(maybe), cool pocket knives, milk chocolate, creepy tax havens, and most importantly, Goldfish crackers.

Linguistic theories suggest that the earliest such devices might have been popular with watchmen or sailors, as personal timekeeping devices would have been useful in tracking passing time while on duty, hence the name of “watch”

I actually cannot describe how crazy shopping on their website feels. Like look at this watch and the graphics they use to advertise it…

“Cradle of Watchmaking” Geneva.com

I always thought his first name was the anglicised version, John, before learning in the past week that he was French.

Wyatt Houtz, “The human heart is an idol factory: a modern critique of John Calvin” PostBarthian.com

a tiktok? a tweet? I don’t even remember and I cannot for the life of me track it down

This is one of my favourite Michel Legrand compositions! “Watch What Happens” is not originally from Les Parapluies de Cherbourg as it is usually purported to be in recordings, but originates in the earlier Lola. In the film, the motif of “Watch What Happens” is the theme music of Roland Cassard, a character who then reappears in Les Parapluies, bringing with him this tune, where it is reimagined first as “Récit de Cassard” and then later as a jazz standard. This is a very pedantic and unnecessary footnote :)