(note to readers: I have once again used too many images, so if you are reading this as an email, you might need to view this newsletter in your browser to read to the end!)

beannachtai na bealtaine!

I’ve been thinking and reading and writing a lot about the intersections of art with other areas of life lately. In a recent newsletter, we looked at the ways in which how we look at, experience, and define art is deeply conditioned by politics and sociological forces. Elsewhere, I’ve been trying to understand the intersections between artistic depiction and science and technology— this is a relationship currently unfolding in the development of and polarised discourse surrounding ‘artificial intelligence’ technologies, and elsewhere throughout contemporary and historical scientific development.1

This week, I wanted to talk a little bit about a recently rediscovered fascination of mine: the Art of Paleontology!2

As is so often the case, this began with a wikipedia spiral.

I was reading about the blue whale(as we all know, it’s earth’s biggest animal!) which led me to a list of the largest and heaviest animals, which is a delightful treasure trove of other lists to click on, like the list of largest fish(which sent me further into the list of longest fish - the whale shark is at the top of both lists, btw) or the list of largest prehistoric animals and the curious article (which has been flagged by wikipedia editors for “Outdated information and unreliable overestimates”) dinosaur size.

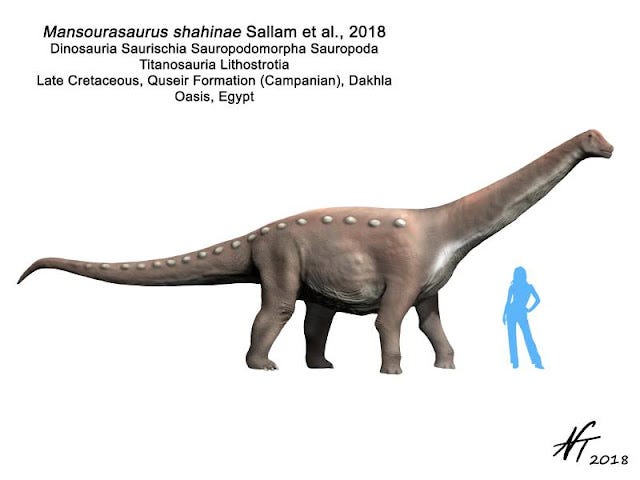

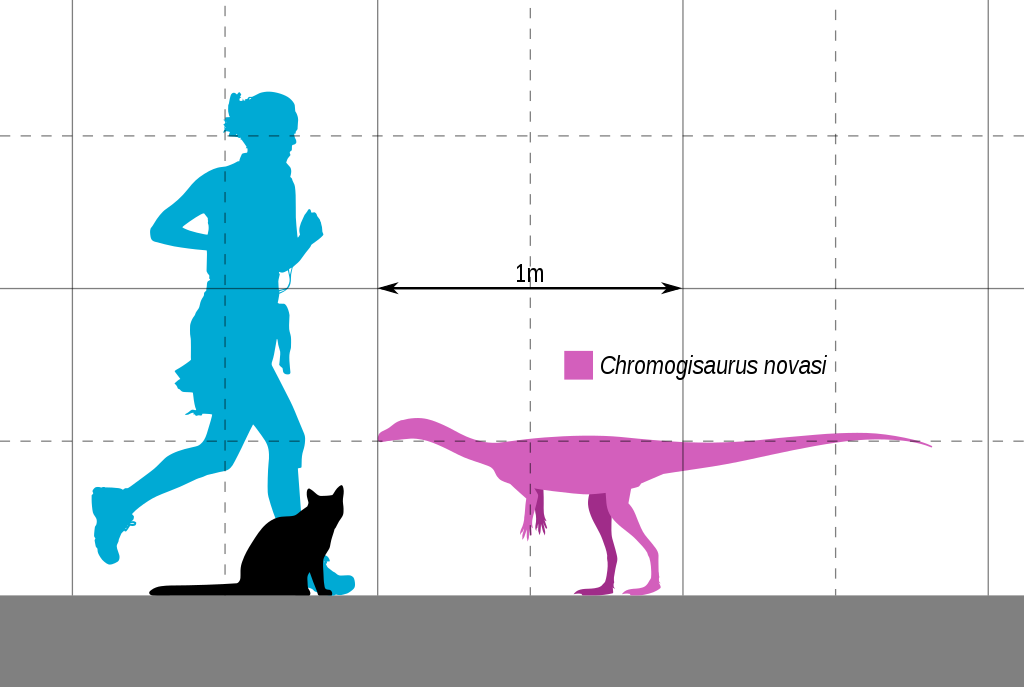

These are all pages full of interesting information and charts and lists, but what really grabbed my attention was all the images, especially of the prehistoric animals - infographics with size comparisons, speculative designs, etc. which do so much to illustrate the information we have about these creatures, and to try to realise the scale and presence of animals we have no way of actually seeing.

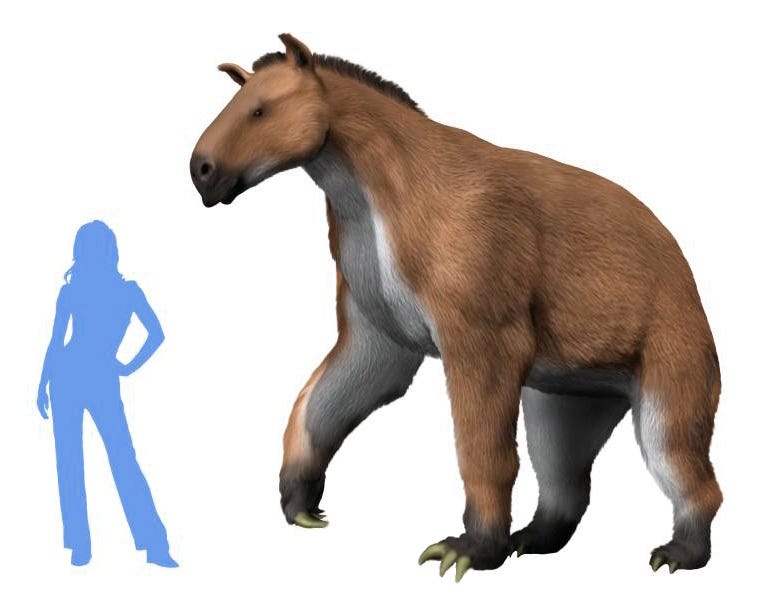

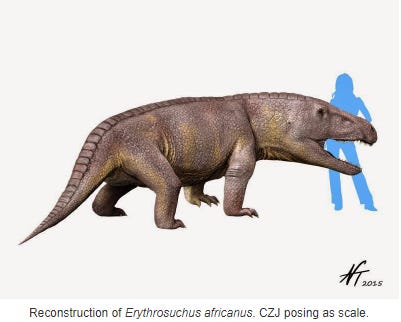

I became weirdly fixated on one thing: the people for scale. Once you notice them, you can’t unnotice them. They’re silhouetted, non descript, often “average height”(according to whom?). Yet they appear distinctly as different characters. A lot of them are just a simple, basic silhouette, designed to give an approximation. In lots of shark or whale images, there’s a scuba diver guy(cool). Sometimes our people-for-scale are doing fun little poses, or waving at the viewer, such as in the below.

But my absolute favourite recurring character in my wikipedia deepdive is this one:

Who is she? The bootcut jeans, the hair moving in the breeze, the powerful, sassy pose as she stands so confidently next to this wild Miocene ungulate! This same silhouette appears for scale in about a dozen other images I found while scrolling through wikipedia lists, but I love the extra personality given to this figure, who’s basically there as a stand-in measuring stick. Sure, sometimes illustrations get a little fanciful - the person for scale gets scuba gear for an underwater scene, or might wave a hand instead of simply standing blankly. But this is so specific, so intentional, so fun for a scientific image. Fascinated, I started googling things like “who makes dinosaur scale images” and “who is the person for scale in science diagrams” and other useless phrases that turned up absolutely nothing of use. I reverse image searched the blue silhouette, but only got more wikipedia articles with more illustrations, or random websites hosting clearly stolen art. Circuitously, I found myself back in the wikipedia spiral, and back to the easiest and most obvious way to track down the source: by looking at the source.3

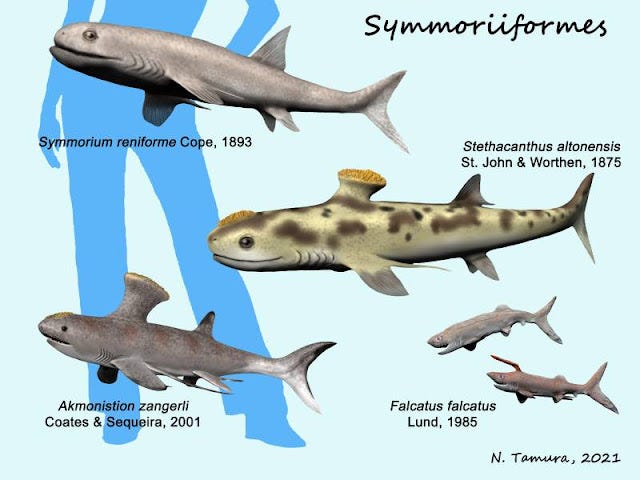

Wikipedia sources their images, I finally remembered, and luckily for me, the source behind all of these illustrations is a prolific paleoartist with an excellent blog and a commitment to bettering the paleoart of Wikipedia: Nobu Tamura.

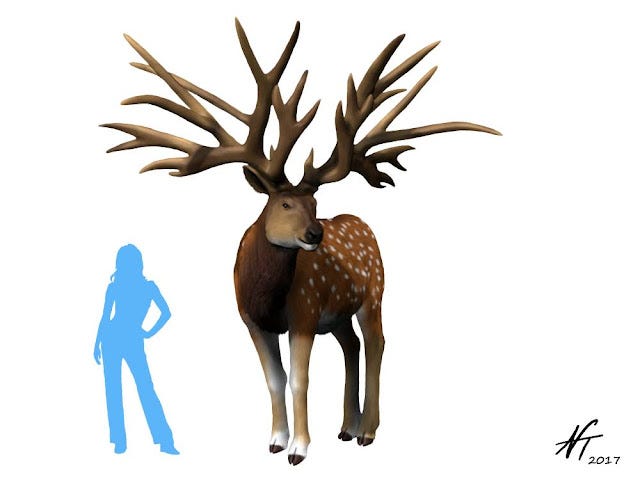

Tamura’s art portfolio is super impressive, extensive, and dedicated to following contemporary research and scientific findings while maintaining creative and original designs. His work is not limited to a specific period or type of prehistoric animal either, but includes a huge and impressive range of creatures, all lovingly and carefully illustrated to give them new life. They are also quite often accompanied by my paleoart bestie, the for-scale supermodel.

Viewing the images directly on his blog, I really appreciate that Tamura includes details about the animal depicted, and makes reference to research and papers related to palaeontological findings, as well as occasional commentary. For the above, he writes: “The males of this large prehistoric deer from Europe developed extraordinary antlers which look a bit like those of the legendary Pokemon Xerneas.” which is just one of several Pokemon references I came across in his work.

I love everything about this!

In a 2016 interview, Tamura, who is a physicist as well as an artist, talks about how in the early days of Wikipedia he noticed that articles on dinosaurs and prehistoric animals were often devoid of images, and that he wanted to try and contribute, but struggled at first to produce illustrations that met current scientific standards, as our understandings and imaginings of these creatures are constantly evolving.

“Rather than giving up or finding a new hobby, Tamura just worked harder and smarter, soliciting feedback from Wikipedia editors on how he could better render extinct reptiles. He looked up the latest scientific articles describing the species he was working on and started sketching. He got better.”

It’s really interesting to hear about his process, which has led to the creation of over 1500 illustrations, and the way that these images reflect and are in continuous dialogue with contemporary palaeontological findings:

Scientists aren’t just collecting and describing fossils — they’re using biomechanical analysis to reconstruct how dinosaurs would have stood and moved around. And advanced techniques are telling us more about the feathers and other soft tissues that would have covered the animals, including pigmentations.

The work of paleoart and paleoartists is pretty extraordinary - they have to blend the imaginary worlds of our envisioned past with the ever changing scientific progress that is being made into better understanding it, and in doing so they help paleontologists and lay people alike to better see the past and to try to locate ourselves within and alongside it.

A few other delightful characters from the palaeontological array on Wikipedia:

The world of palaeoart is such a fascinating one, and alongside the delightful artwork being produced and disseminated, there are also really interesting discussions in the community around palaeontology and paleoart that guide us to think about the impact and value of these images for scientific enquiry, exploration, and education.

In “Paleoart as Science”4, Adrian Currie writes about the impacts of artistic depictions of prehistoric creatures on actual paleontological research as well as public perceptions, and the ways that the imagery of paleoart serves to shape the way we think about these animals. We can even propose that paleoart is not just a tool for illustrating research or aiding in science education, but acts as its own epistemology in the paleo realm, where artists are not only making abstract evidence concrete, but engaging in scientific hypothesis and conjecture, playing a key role in the network of physical, chemical, and imaginative evidence that we must put together in the work of reconstructing extinct animals.

“State of the Palaeoart”5 is a commentary by Mark P. Witton, Darren Naish, and John Conway, which also provides really interesting commentary on the importance of paleoart, and the way that it is undervalued and the inaccuracies and plagiarism that often result in the production of art. By the same authors is the book All Yesterdays: Unique and Speculative Views of Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Animals, which I read back when it was published in 2012, and which has become a contemporary classic in the realm of paleoart and the decades of poor science, misinformation, and more that have plagued it. The book includes fantastic illustrations which demonstrate the ways in which paleoart designs must often make serious interpretive decisions about how they represent abstract data from fossil records, and the ways that this can lead to wildly different and often incorrect results, which can remain in the collective imagination long past the point where paleontology has moved past it. Everything from the Crystal Palace dinosaurs to the monstrous carnivores of Jurassic Park are works of pop paleoart that shape how we imagine and understand our planet’s ancient inhabitants, often in distorted, outdated, and non-evolving ways.

In my deep dive into the wikipedia archives on paleoart, and my discovery of the incredible palaeo illustrations of Nobu Tamura, I have finally found exactly one clue in my search for the enigmatic figure who appears with so many dinos and extinct creatures in his portfolio. In a 2015 blog post, the figure is identified(as far as I could find, this is the only time!) in a caption as “CZJ”.

I wasn’t able to find a source image that matches(yet), but I think we can say decisively that we’ve figured out the mystery behind this iconic for scale figure. How bizarre and wonderful it is to have images like this to guide our visions of the past! What a world we live in that our wikipedia articles are being illustrated by the image of Catherine Zeta Jones hanging out with an incredible array of prehistoric and extinct animals!

Art and artists do so much to guide scientific study and discovery, in this field and beyond. From the ongoing discussions in the paleoart community to more recent AI art scandals in scientific journals, we can see the real world implications and intellectual dangers of undervaluing the work of artists in science fields. The paleoart images I’ve been finding in my weird little internet odyssey are strange, magical reminders of the endless mysteries of our world and worlds past, and an incredible intersection of art and science, inside jokes and scholarly exploration!

For an upcoming newsletter on Arthur Conan Doyle’s “Sherlock Holmes” stories, I’ve found myself researching the impacts of electrical experiments and the spread of electricity as a new technology on fashion and contemporary popular culture, and learning about hydraulics while thinking about the inclusion of new technology in popular literature in this context.

Or palaeontology, if you’d prefer. I think I ended up using both spellings kind of interchangeably in this piece because there are just too many vowels in there for me to reliably keep track of.

This was a sad moment for me. A major research L.

Adrian Currie, “Paleoart as Science,” Extinct-The philosophy of palaeontology blog, 27 February 2017. https://www.extinctblog.org/extinct/2017/2/27/paleoart-as-science

Mark P. Witton, Darren Naish, and John Conway, “State of the Palaeoart,” Palaeontologia Electronica, September 2014. https://doi.org/10.26879/145