“we live in a twilight world, and there are no friends at dusk”

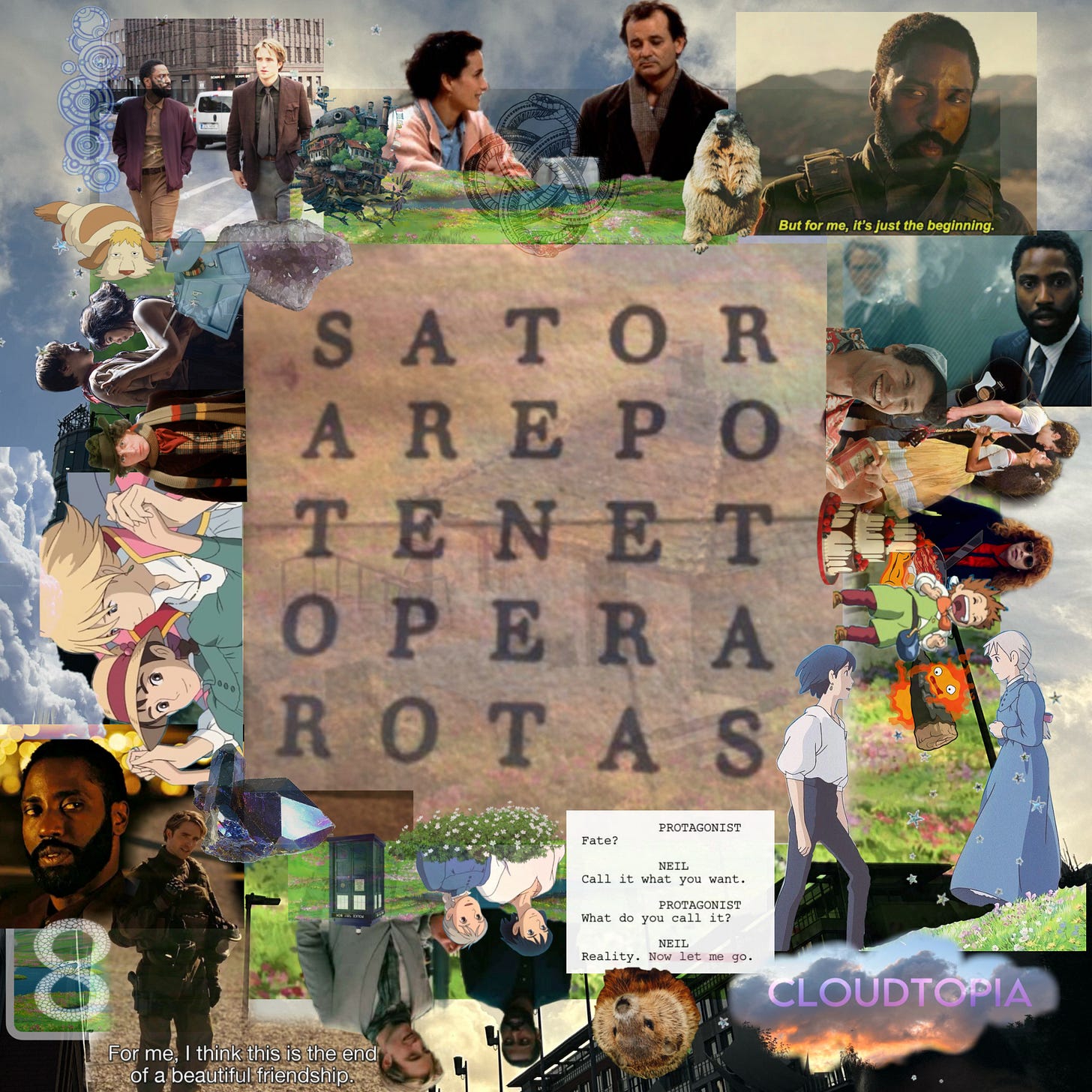

Groundhog Day is arguably the quintessential time loop story. A man finds himself in a situation he is unhappy about, he goes through a series of occurences, coincidences, interactions; the following morning he wakes up to find that things feel oddly familiar, and soon realises that he is reliving the day, which he continues to do for a period of repeating days until he learns the patterns and understands the people around him, and through trial and error finds a way to perfect the outcomes of the day and finally escape the loop.

In this time loop story, the man in question is Bill Murray as Phil Connors, and the day in question is February 2.1 Sent to the small Pennsylvania town of Punxsutawney to report on their traditional Groundhog Day celebration, Phil is dismissive of the entire affair, openly rude to the people around him, and desperate to finish the report and leave town. The time loop scenario he finds himself trapped in undermines this central goal of escape as he is forced to relive the day again and again, with the same town he looks down on, the people that he hates, and the day that he initially rejects. As the day recurs, he tries every possible tactic to escape, but as he lives out the day, he starts to know it better - he can predict what people will say, where they will be, the little accidents that happen during the day - and through this practice and routine, he ends up, unintentionally and then intentionally, getting to really know the people and places around him. By the end of the film, he knows the life stories of most of the town’s residents, and he regards them as old friends, replacing his original disdain with genuine fondness. His experiences in the town reveal to him its inner beauty, and the process and routine of the day forces him to become the thing that changes in the world.

This is what I love about time loop stories - they reveal the immense potential in small things, and the opportunities we have in every day, no matter how bored or trapped we might feel, to better ourselves and the world around us. What if we could take the time to get to really know people? To really understand the places we find ourselves moving through every day? What if we had the time to make a change? There is so much beauty in the mundane, here, and an incredible sense of optimism in the capacity for growth, change, and understanding.

While(I presume) none of us have experienced a time loop like this in our own lives, I think most people can intimately relate to the experience Phil goes through in the movie. It is so easy to feel trapped in life. Every day, we wake up, go through our routines. Maybe we go to an office, or classes, or a restaurant, and we do our tasks, always the same as the day before. For most people, the dullness of routine can feel like an all consuming force. At the end of every day, we know the loop is just going to start again. Yet in the story of Groundhog Day, the only way that Phil finds progress in the story is through breaking the loop and actively choosing to do things differently, to dig deeper, to try new things. He is constantly finding new meaning and connection as he lives out each day in Punxsatawney, and ultimately, he is able to break the cycle. The movie’s ending is every worker’s fantasy: waking up to a truly new day. The core idea is that things can change, that the world and we ourselves can be a little better and a little kinder with every repetition of the banal.

Maybe we get it right this time.

When I set out to write this, I almost immediately learned that I had been using the term ‘time loop’ incorrectly. There are the proper time loop stories like Groundhog Day (and numerous other notable films, short stories, television episodes, and even video games); and then there are ‘causal loops’ - I’ll give you the explanation provided by the Wikipedia article because I think it adequately sums up what is interesting to me about both loops:

The time loop or temporal loop is a plot device in fiction whereby characters re-experience a span of time which is repeated, sometimes more than once, with some hope of breaking out of the cycle of repetition. The term "time loop" is sometimes used to refer to a causal loop; however, causal loops are unchanging and self-originating, whereas time loops are constantly resetting: when a certain condition is met, such as a death of a character or a clock reaching a certain time, the loop starts again, possibly with one or more characters retaining the memories from the previous loop.

I won’t bore you further with the minutiae of different types of temporal loops, so let’s get straight to the point. What I really was thinking about when I started reading about loops is the 2020 film Tenet. Infamous for its weird cinema debut and box office performance, widely hated and criticised for being too long, too confusing, pretentious, unwatchable, etc., Tenet is at its core a classic, formulaic James Bond style spy story (complete with an M figure, a Bond girl in distress2, Q, a wealthy Russian arms dealer, etc.) —the story follows an operative known simply as the Protagonist(John David Washington, one of the great nepo babies of our time) who travels the world in a race against time to stop the antagonist from assembling and using a doomsday device. The plot is, however, complicated by a little understood phenomena in this world called inversion, whereby the entropy of matter can be ‘inverted’, causing it to experience the passage of time backwards. Inverted weapons from the future are appearing in the present day, ranging from bullets to large scale technology sent backwards as part of a temporal cold war.

I’ll be honest: when I first heard about Tenet, I was totally uninterested. I do not generally watch this genre, and when people tried to explain why the time travel is cool, it was always “oh they travel through time by going backwards through time”, which sounded nonsensical to me, like, okay, yeah, they go back in time? You have just described all time travel movies?

But when I finally watched it myself this year(and became so immediately enamoured that I watched it twice in one day3), I learned that 1. I was misunderstanding the explanation, and the backwards motion of inversion in this movie is actually unique and extremely cool to watch, and 2. understanding the time travel of the film does not really matter that much.

As the scientist(Clémence Poésy) who teaches the Protagonist about the basics of inversion explains, the best way to understand the film’s temporal reality is not to overthink, but to feel. Things move forward, things move backwards, but much like the interlaced fingers of the Tenet organisation’s secret gesture, the back and forth motion of time and events in the film is all part of the same whole, happening in parallel, always connected.

“What about free will?” the Protagonist asks, to which he is told “either way we run the tape, you made it happen.”

A bullet is shot out of a gun. The bullet emerges from the splintered wood and returns to the gun. In the flow of time of this story, things happen out of sequence, are reversed and repeated. We may feel trapped in the loop, but it all matters.

Protagonist: “What do you believe?” Neil: “What’s happened’s happened.”

It takes a long time for the movie to become fully immersed in its time travel, and it’s only towards the end that the causal loops of the story really fall into place. Early on, we see inverted bullets, and eventually entire action sequences incorporate oppositional temporal motion, perhaps seen most thrillingly in the Tallinn car chase or the Protagonist’s fight with an inverted figure in the Oslo airport, two sequences repeated—so nice we get to watch them twice!—once forward, once moving backwards in time. The reflection of action through these inverted scenes is incredible, playing with cause and effect in clever ways to keep the viewer engaged and asking questions as the timeline begins to zig zag, crossing and reencountering earlier parts of the film story; finally closing the loop.

This is both the promise of the film - that action and causality are always possible, that we can go back, that we can fight to save the day even against the unyielding march of time - and simultaenously its existential threat. Our future is both danger and endangered. The ultimate problem facing our Protagonist is an algorithm, being assembled piece by piece, sent backwards in time from a wartorn, vengeful future. Once assembled, it would invert the entropy of the entire world. If this comes to pass, it is more than just individual objects or people swimming up stream: everything goes backwards. Everyone is doomed.

Just as I think that time loop stories can reflect a lot of the frustrating and mundane experiences of real day to day life, the twisted temporality of Tenet also speaks to our experiences of time as it relates to memory.

This is explored perhaps most clearly in the relationship between arms dealer Andrei Sator(Kenneth Branagh) and his wife, Kat Barton(Elizabeth Debicki). Sator is possessive and abusive, essentially holding his wife hostage in their relationship by keeping blackmail against her in the form of a forged painting and denying her custody of their son. Kat describes her husband as “playing grubby little games with a wife who doesnt love [him] anymore” and we can see the way their relationship plays out as a sort of time loop, a recurring series of actions and reactions by which she is tortured and trapped; and there is no escape in sight. The trauma and abuse she suffers throughout the film puts her out step with passing time, caught in the loop.

It is only when the causal loop of Kat’s storyline on screen is closed that she is able to free herself: when the Protagonist and Kat first start working together, she recounts to him a holiday she and Sator took on his yacht, a brief, happy period where she tried to give the relationship another chance. But, she recalls, when she went off to shore one day, she returned to the yacht to see a strange woman diving off the boat, and to find her husband gone.

At the end of the movie, both Kat and Sator have travelled backwards to this moment again, independently. Sator goes back to this one happy period with the intention to die, an action which will set off the algorithm and end the world. Kat is dispatched to keep him alive. Both outside of normal time, they return to this pivotal moment in the relationship, which, static in memory, remains a point of possibility just before the relationship ends or begins again, and before Sator either dies or lives. Their lives and memories hinge on this moment, as does the fate of the entire world.

As spies and operatives tell us throughout the film, “we live in a twilight world.” The moment in time where we place ourselves is a moment of just before, the liminality of twilight between day and night, lightness and dark. Kat, returned to this moment, convinces Sator to stay alive a little longer to watch the sunset with her. There is a little infinity to be found here, in this moment before the sun goes down, before the world ends(or, continues on). But “there are no friends at dusk.” Ultimately, Kat is the one to take control, and in doing so, to close the loop. She is the one to kill Sator, and the woman her past self enviously watches dive off the yacht into freedom is herself.

“What’s happened’s happened.”

Another of the film’s causal loops is the temporal cold war, where weapons and operatives from the future return to the past to enact its destruction. These acts of war may be in the future, but the stage for the end of the world is already set, here and now. Through our actions today, the cold war is being waged already.

Crucial set pieces for this movie reveal to us the ways in which the world’s doomed future—Sator reveals that the war is being driven by an extreme ecofascism in the future, seeking retribution against our indifference and inaction to apocalyptic climate change already occurring in our time—is already unfolding. The freeports, high security facilities such as the one the film visits in Oslo where the ultra rich can hide away investments without paying tax, and where employees place the security of the freeport valuables above their own safety. The secret cities, entire places filled with real people, written off the map and disregarded in order to mine radioactive materials for the benefit of nuclear arms development. The residents of secret cities bear the brunt of this militaristic undertaking, suffering the longterm effects of radioactive exposure, including film antagonist Sator who is revealed to be dying of cancer after his past in the town of Stalsk 12. Part of the algorithm is obtained in the film’s opening sequence at the Kiev Opera House, where the civilians captive in the auditorium will be sacrificed for the temporal mission.4 The very end of the world will take place on a billionaire’s super yacht. The recklessness of capitalism, of militarism, and of governments today, both in their impact on the environment, and on the lives and livelihoods of ordinary people, all of whom are made sacrificial lambs to these great forces, are the very same things that are driving the destruction of the future, and in this story are the causes for the future’s vengeful war on the past.

In the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, Orpheus ventures into the underworld to rescue his wife, Eurydice, after her death. He must lead her out the underworld, but is warned that if he looks back at her, she will be lost forever. In just about every version of this story, he looks back. In trying to bring back his irrecoverable past(his life with Eurydice), he is the source of its own destruction. The turning back, an act of love, or perhaps doubt, the need to know that she is there behind him, becomes an act of violence.

In explaining the motives of the future’s forces in the temporal war, Sator tells the Protagonist: “they have no choice but to turn back. We’re responsible.” The past is always the motive, and turning back to it is the greatest danger.

As the film tells us, “speaking to the future is easy.” But does it speak back? Sator communicates with his future comrades through time capsules, which much like their real world counterparts, allow the transfer of matter through time in the narrative. Elsewhere in the film, communication across the various points in time where war is being waged occurs through memory, through the records of history, through messages left to “posterity”. In these ways, we are always reaching out to the future, always in contact with what is to come.

“What do you believe?”

My favourite loop of the film is in the relationship between the Protagonist and Neil(Robert Pattinson). When they first meet, the two develop a quick rapport, and Neil seems to know a lot about the Protagonist(“I prefer soda water,”, he claims when Neil orders a diet coke on his behalf, “no, you don’t,” Neil responds.), and the Protagonist begins to wonder if Neil simply has good intelligence on him, or something more.

Neil tells the Protagonist (and the viewer) several times that “what’s happened’s happened”, which he argues is “an expression of faith in the mechanics of the world”. The past is neither predetermined nor is it open to change. What will be will be, but we have to make it happen.

During the climactic action sequence of the ‘temporal pincer’ maneuver, the audience learns that Neil carries a unique totem, a small object attached to his gear that we have seen before during the film, revealing that Neil has been involved in everything from the start, which the viewer might only be able to discover if rewatching the film from the beginning. In a final scene, Neil reveals that he has known the Protagonist for a long time, telling him that “for me, I think this is the end of a beautiful friendship.”

Having been inducted into its esoteric ranks, the Protagonist will go on to found Tenet in the future, to return to the past and set the events of this story in motion, to befriend and work with Neil. The Protagonist “[has] a future in the past,” while Neil’s future is left uncertain. Yet, through their intersecting, out of sequence timelines, their stories are intertwined, their essential choices and actions each reliant on the other. In their discussions on free will, fate, and paradoxes, it is clear that across their interconnected pasts and future, the thing most connecting them is decision. They decide to fight the war, they choose to trust, agree to work together. Knowing the future, they still keep trying. We always have to choose.

“I’ll see you at the beginning, friend.”

In a brutal war driven by secrets and corruption against a mysterious enemy, two people with a bond that traverses time must uncover conspiracy and danger in the hopes of preserving the future. We see this story in the causal loops of Tenet, yes, but also in Hayao Miyazaki’s 2004 animated adaptation of Howl’s Moving Castle. The film adaptation of this story sets the fantasy tale of wizards and curses against the backdrop of brutal, dehumanising warfare. Fighting in the war, the wizard Howl is ouroboros-like as the more he tries to evade and work against the forces of war, the more he himself is pulled into its destructive cycle, corrupting and entrapping him, which will eventually lead him to lose himself entirely in the battle.

The force of change that enters his life comes in the form of Sophie, a young hatmaker transformed into an old woman due to a magical curse. The first time the two meet in the film, she is harrassed by soldiers while traveling through town. Howl comes to her rescue, pretending to recognise her, and helps her escape. It is only much later after they have ‘met’ again that she realises that Howl knows who she is. Near the film’s end, Sophie and the fire demon Calcifer travel back in time in order for Sophie to witness a scene of Howl’s childhood which will help her to save him and to stop the war. Before returning to the present, Sophie tells young Howl to “find [her] in the future!” If we return back to their first meeting we recall that, upon rescuing Sophie, Howl tells her “there you are … I was looking everywhere for you,” Their very meeting, and the subsequent ways in which they each must save one another from the forces of darkness, are products of a causal loop that encircles the entire storyline of the movie, and ties them together across time. And it is only through this extratemporal bond and working together that they are able to break the curses controlling their lives, and escape the all-consuming power of the war they face.

While this film is primarily a fantasy romance, remembered for its beautiful animation, great characters, and iconic visuals, it is also a staunchly anti-war film, inspired in large part by US militarism in the early 2000s, and it is a film that interrogates the loss of humanity in acts of war, the fallout experienced by civilians, and even uses science fiction and time travel elements to represent the complex and painful temporality that emerges in the spaces of violence and militarism.

“Find me in the future”

In the classical Greek traditions of tragedy, a tale of suffering and woe was intended to bring about catharsis, a cleansing emotional release, in the audience. Just as they are to us today, many of these stories would be familiar to contemporary viewers, who would thus know the ending that was to come. Catharsis does not abide by spoiler warnings, but instead much of the satisfaction and enjoyment of a great work of tragedy might even come from knowing what violent ends, ironic sacrifices, or heroic deaths might be waiting at the end of the story. Throughout the film, Tenet often positions itself as a tragedy - it takes on the language of theatre in the naming of the Protagonist, in referring to other characters in universe as antagonists, or when Priya(who advises the Protagonist regarding Tenet, played by Dimple Kapadia) describes the apocalypse as “end of play.” Many of its major players die in the end, and throughout the story, their fates are set. We know that at the end of Orpheus and Eurydice that she will die, and that he will fail. We know that at the end of Tenet the Protagonist will start the whole loop again, in the future/past; we know all that he will lose in the process.

In the mythically-inspired Broadway musical Hadestown, the narrator Hermes introduces the story of Eurydice and Orpheus as “an old song, and we’re gonna sing it again.” At the conclusion of the story, he laments an echo of this: “it’s a sad tale, it’s a tragedy, it’s a sad song, but we sing it anyway.” Through the song cycle of Hadestown, we are reminded of the timeless catharsis of the myth, that even though we “know how it ends”, we “still begin to sing it again, as if it might turn out this time”. Storytelling creates an infinite, cathartic timeloop, one where the story can begin again and again, where characters can live and die and return again to take a bow.5

“there are no friends at dusk”

Death, in Tenet is the ultimate breakdown of temporal causality. Death is, of course, inevitable. When it comes, it is often violent, brutal, always final. But within the causal loops and time traversal of the story, life and death are essential choices that everyone must make. The Protagonist is initially inducted into Tenet when, after a mission gone wrong, he chooses to take a CIA provided cyanide pill rather than give up his team. When he awakens, he learns that the pill was not his end, but a test. It is only by this choice that he enters the time war, in spite of later revelations that he has always been caught up in the war. His involvement is inevitable, and yet the decision is essential.

In trying to stop the creation of the world ending algorithm, both the Protagonist and Neil know that they know too much as operatives:

Protagonist: and when we’re done, they’ll kill you

Neil: won’t you have to do that anyway?

Protagonist: I’d rather it be my decision

Neil: so would I. I think.

The future is already determined: at the end, no one makes it out alive. Yet it matters what choices lead to that. Neil and the Protagonist each have moments in the film where they must choose life or death. While Sator always plans his own cataclysmic death, it matters that Kat is the one who kills him. It matters that the Protagonist is not just chosen to join Tenet, but will choose to begin it.

“we live in a twilight world”

The catharsis of the causal loop: we know that the story will always return here.

Just as much as the outcome, it matters who has the decisions in their hands, and what choices are made. Cause and effect. We might not be able to change it all.

Maybe we change the world, maybe we change ourselves, maybe the story always ends the same way. Effect and cause. Maybe we get it right this time.

What’s happened’s happened. But we have to take action.

We tell the story anyway: the causal loop as hope.

I leave you for this week with a time loop poem by Naomi Shihab Nye, transcribed from the collection Bless the Daughter.

Backwards

The poem can start with him walking backwards into a room.

He takes off his jacket and sits down for the rest of his life,

that’s how we bring Dad back.

I can make the blood run back up my nose, ants rushing into a hole.

your cheeks soften, teeth sink back into gums.

I can make us loved, just say the word.

Give them stumps for hands if even once they touched us without consent,

I can write the poem and make it disappear.

Step-dad spits liquor back into glass,

Mum’s body rolls back up the stairs, the bone pops back into place,

maybe she keeps the baby.

Maybe we’re okay, kid?

I’ll rewrite this whole life and this time there’ll be so much love,

You won’t be able to see beyond it.

You won’t be able to see beyond it,

I’ll rewrite this whole life and this time there’ll be so much love.

Maybe we’re okay, kid,

maybe she keeps the baby.

Mum’s body rolls back up the stairs, the bone pops back into place,

Step-dad spits liquor back into glass.

I can write the poem and make it disappear

Give them stumps for hands if even once they touch us without consent,

I can make us loved, just say the word.

Your cheeks soften, teeth sink back into gums,

we grow into smaller bodies, my breasts disappear.

I can make the blood run back up my nose, ants rushing into a hole,

that’s how we bring Dad back.

He takes off his jacket and sits down for the rest of his life.

The poem can start with him walking backwards into a room.

Thanks as always for reading. I’ll be back next week with another newsletter talking about memory and capitalism and stories, and possibly another little reflection for the Winter Solstice! Until then, I’ll be:

making orange and kumquat marmelade for holiday gifting,

attending protests and working with local orgs for justice in Gaza and beyond

trapped in the time loop of my day job

wearing a high quality mask in indoor & crowded spaces to protect myself and the people around me from illness.

I hope you’ll be doing some of the same.

see you in the next loop,

isobel

I am obligated to say that this is also James Joyce’s birthday, and (nearly) coincides with Imbolc, the beginning of spring in Irish tradition.

Kat’s positioning as the main female character in this movie is definitely one of the movie’s weak points. Her primary role in life is Mother, and her position in the story is entirely defined by her treatment by and relationships to men, primarily Sator, but also the Protagonist and even her son Max. This sort of characterisation of women in his movies is my primary issue with Christopher Nolan’s filmography, it would be good if he could use a little of the energy he focuses on thinking about quantum mechanics and such on thinking about how women are people. Just an idea.

I couldn’t find anywhere to say this in the main text so I’m just putting it here: even with all my pretentions about this movie, please understand that this movie is cool. You get to watch a car chase where half of the cars are going backwards. John David Washington fights off a bunch of Sator’s gangsters with a cheese grater. You get to watch a beautifully choreographed fight scene that looks incredible both forwards and reversed. You get to see them crash and blow up an airplane! They really crashed a real airplane when filming this movie and it is so cool!

I initially thought that the Kiev sequence was a depiction of the Nord-ost seige, a real world incident in 2002 where a Moscow theatre full of performers and patrons was taken hostage by a group of armed insurgents. Special forces decided to raid the theatre, releasing a chemical agent that affected both hostage takers and hostages who, without knowing, breathed in the gas, leading to high casualties and hospitalisations. While these events do not exactly mirror the events in the film, there are clear similarities, and writers including Maria Tumarkin, who wrote about the incident in her book Traumascapes, have criticised the handling of the hostage crisis and the extreme risk and danger the hostages were put in by the special forces decision, in the interest of militaristic anti-terrorism.

This is, for readers of my Riverdale newsletter “the town”, what makes that show so great too, by the way - there is no end or beginning to the Riverdale story. There is always the town and the diner, love triangles and hamburgers. There is always Archie and Jughead, Betty and Veronica, the rest of the gang. They’re always in a time outside of time, (which is also always the 1950s.) At the end of the world, they can try again, try to tell a better story.