Once upon a time people lived the simple life. Things were better. We wore beautiful clothes and ate beautiful food and our days weren’t consumed by work and the internet and whatever other horrors you think are ruining your life.

This story isn’t true, but it’s nice to think about, right? Our social media spheres are obsessed with this fantasy, and it can be found everywhere from the rise of cottagecore, of tradwives(and the right wing propaganda algorithmic pipeline they so often lead to), of anti-grind culture, and plenty of other trends and communities which have emerged out of this dream in varying ways. What exactly we aspire to, and why, however, diverge greatly.

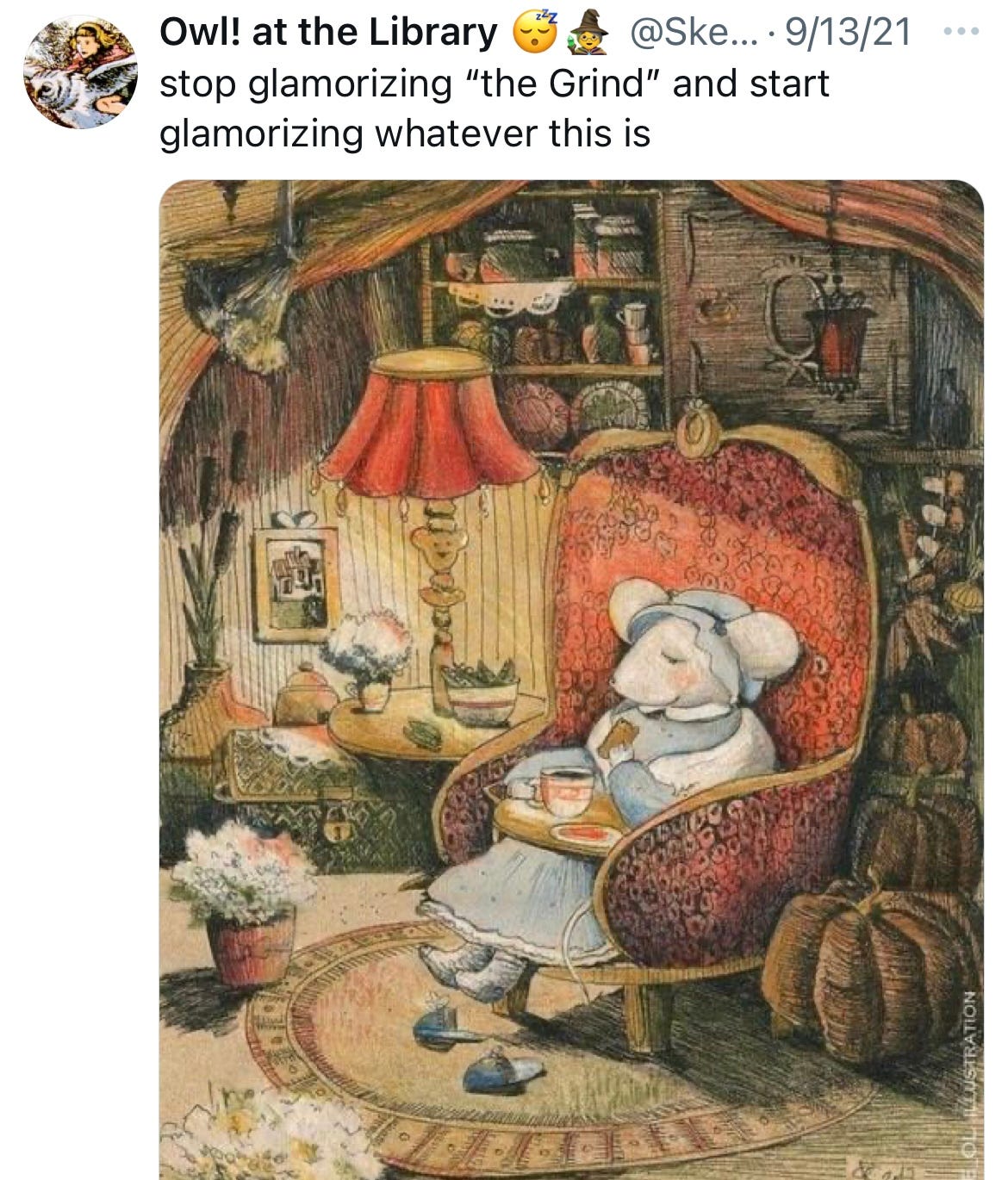

On the one hand, there are communities online that are reconsidering the way we prioritise work and accomplishment in contemporary culture, communities that “don’t dream of labour”. Once upon a time there was life outside of jobs and work and the crushing, all consuming nightmare of late stage capitalism:

And on the other hand, the fantasy of that better, simpler life is championed by regular old fascists as a white supremacist dog whistle that speaks to regressive understandings of gender, race, and class. Once upon a time, it claims, the world had hierarchies and rules that were made for certain people. The rest of that story—the suffering that results and the people and experiences that are left out—doesn’t matter to them.

I’m thinking a lot about this in the context of that Ballerina Farm article,1 the discourse about Nara Smith and her trad-adjacent tiktok ilk that has abounded in recent months, and also because I’ve spent lots of time this summer watching weird old fairy tale films on the criterion channel and dreaming of the fantasies that they—that all of this—promises. I’m not sure what I can say about any of this that hasn’t already been think-pieced to death, but I wanted to take a little time to reflect on the relationship between labour and fantasy, as it emerges in various spheres, from the fairy tale dreams of paupers-turned-princesses to the modern culture war construct of the trad wife.

Cinderella is kind of a quintessential fairy tale. In the end, the girl reunites with her one true love and lives happily ever after, but I think the core fantasy of this story isn’t really the true love thing, or the beautiful shoes or the pumpkin carriage - it’s the escape from domestic labour. Cinderella goes from serving her cruel family members, sleeping in the ashes of the fireplace, working night and day to keep the house, to being a princess, someone who is served rather than servant, someone free of the burdens of labour. Isn’t that the real fantasy of this story? Leaving the work behind?

One of the fantasy worlds where this dream is perhaps most apparent is Jean Cocteau’s 1946 film La Belle et la Bête(Beauty and the Beast). We are introduced to the titular Belle in her family home, where she is forced to keep house and cater to the whims of her selfish, materialistic sisters, her pompous brother, and her failing father. As the prototypical virtuous fairytale heroine, Belle does her chores and helps her family without complaint, and when her father offers to bring the children gifts when he returns from a trip, while her sisters request extravagant goods, Belle’s humble request is for a single rose. In a twist of fate, picking a rose from the Beast’s garden is what leads to Belle’s father having to send her to live in his castle, ripping her away from the mundane labours of her home life and transporting her to the dark, magnificent world of the fairy tale.

In the Beast’s domain, Belle is attended to by the magical forces of the castle. She is no longer a servant, and is able to discover another way of life and a mode of being that is separated from the labour and care she performs for others. When she returns home to see her ill father, we learn that the order of the family has fallen apart in her absence, with her siblings unwillingly taking up some of the work of the house, which they immediately try to push back onto her when she returns, all while mocking her changed appearance and the gifts given to her by the Beast, which they see as extravagant and opposed to her former role in the house.

Perhaps most interesting about the domestic hierarchy of the film is that while the family pushes all of their chores and work onto Belle, with the hopes of raising themselves above her, Belle’s life in the castle subverts this by freeing her of her work without demeaning someone else, completely removing the visible element of labour in the form of what she calls the ‘invisible servants’ of the living castle. It is never clear how this magic works - are chores completed on their own, with the living, moving body of the castle performing tasks, or are the labourers in this realm simply away from view, externalised so that Belle(and the audience) does not have to acknowledge the displaced inevitability of work when we enter the fairy tale world of the magic castle? Throughout the film, the dynamics of labour, identity, and domesticity are an ever shifting undercurrent in the story that suggests a meta narrative about how we value(or more aptly, undervalue) different forms of work and the (sometimes literally) invisible labour of domesticity.

Peau d’Ane(Donkey Skin), a spiritual successor to La Belle et la Bête, also articulates a relationship between labour and fantasy. Released in 1970, the film is Jacques Demy’s retelling of another classic French fairy tale, with an ironic sensibility that muddies and subverts the traditional trajectory of these stories. Like Belle, the heroine of Peau D’ane is forced to leave the home of her father and take on a new role in society, but her path is reversed, as she leaves the comfort and infinite material wealth of life as a princess to don the mantle of Donkey Skin and live in a shack, where she must take on the labour given to her and face the scorn of the townsfolk for her strange appearance and poverty.

Like in other stories, the servants and labourers here are largely left in the margins, existing more as set dressing than as real people. This is first and foremost a stylistic choice here(and an intentional homage to the visuals and special effects of La Belle’s ‘invisible servants’), but it also speaks to the role of work in the world and story of the film, and the fantasy of exteriorised labour. Later on, we see the princess, now known as Donkey Skin taking on work under her new identity, but the film never lets us forget that she is still a princess beneath the disguise, and through magic she retains access to her material wealth, which she reclaims each time she puts on one of her fabulous gowns. This dual identity, which serves again to displace the role of labour in the story, also reinforces the sense of work and fantasy being closely tied together.

Donkey Skin is asked to bake a cake for the prince, who has fallen for her after glimpsing her in town; in a fantasy-musical sequence, she is magically doubled to complete her chores - one version of her, still wearing the donkey skin, reads out the recipe, while another version of her who has put on the gown the colour of the sun, returning her to the beautiful princess version of herself, bakes the prince’s cake. Here, her dual roles are made literal, and we see her as both the princess, the one for whom labour is done, and as the secondary, externalised labourer; yet the roles of each side of her are reversed, with Donkey Skin reading out the recipe to the Princess, who does the baking. Here, the work she performs is more than just the barrier to her real self or normal life, but becomes an integral part of the fantasy, whereby her goals(first of escape from her father’s castle, then of winning the prince’s affection) are predicated on her becoming a worker, and her identity becomes increasingly wrapped up in the cozy, fairy tale domesticity of keeping house, and her playing at doing chores.

Whereas labour is primarily representative of the real world struggles which are surpassed in the fantasy of La Belle, Peau D’Ane fantasises not only about the escape from reality, but about labour as part of an imagined lifestyle, one where the modern world encroaches on the ‘once upon a time’ of its fairy tale setting, with kings reading poetry from the future and fairy godmothers that arrive in helicopters and yes, a princess who bakes in a ballgown.

Labour in fairy tales is simultaneously the signifier of life’s burdens(the dull, difficult mundanity of real life) and of the tireless, selfless virtue of our protagonist(she must have a good-old-fashioned protestant work ethic, be able to keep house; she must deserve the fantasy she will eventually live out).

These motifs through which we see labour represented in these films, such as the invisible servants or the magical doubling of work, appear across a number of fairy tale stories. In many stories, characters are tended to by unseen, magical helpers, or animals turned servants. Underdog heroes go from ‘lowly’ servants to princes and princesses. Magical figures are able to miraculously perform superhuman feats of labour with enchanted assistance. We can go back to the story of Cinderella, (and in particular the 1950 animated film), where we see an overburdened Cinderella dutifully completing her chores as she dreams of being able to do everything in duplicate, assisted only by her animal friends.2 These recurring motifs speak to the essential interest these fantasy stories have in overcoming and easing the great burdens of labour, especially domestic labour. In 2007’s Enchanted, the tendency for the women of fairy tale films to cheerfully take on chores and household work as a central part of their lives is parodied in “Happy Working Song,” where Giselle and a hoard of grimy New York City animals clean the apartment. Here, we see again the way that the hard work is not only overcome through fantasy, but becomes baked into it as a romantic and essential tenet of the fairy tale lifestyle.

So much of the story of modern household work can be traced in these stories—and much like the invisible servants of fairy tales of yore, even more is revealed by what is made invisible in our narratives around labour and fantasy. What is missing? The protagonist of each of these films we’ve discussed so far is a beautiful white woman, and the pseudo-historic settings of the films leave no room for reckoning with either race or class. This is as essential part of the fantasy as well—the real world dynamics of labour and work simply do not exist here.

In the early 20th century, the emerging industry of household appliances revolutionised domestic labour, and advertising campaigns for home appliance technologies such as modern ovens, washing machines, or refrigerators demonstrate a major shift in the narratives around labour in the home. In the article “Technologies of Domestic Labour”3, Satyasikha Chakraborty writes about these trends in British advertising where new appliances were marketed as “electric maids” and marked a trend away from domestic servants in the home after the Victorian era, and parallels this with the realities of domestic servitude in the British Empire and specifically in colonial India, where racialised and caste-based systems of servitude remained firmly in place and actually saw an increase in popularity in the early 20th century. Writing about the narratives around domestic labour in (specifically white) British homes during this period,

Domestic gadgets promised freedom and leisure to wives/mothers, like Hotpoint electric ovens, which advertised: “This Electric Maid frees the Modern Mother”, or “This Electric Maid cooks while the modern mother is Free”. Not just freedom, household technologies like electric ovens and washing machines also symbolized wealth, cleanliness, and modernity, and were crucial for middle-class status.

Rachele Edini writes about these dynamics of class status, race, and wealth in a 20th century American context, and the way that the fantasy of invisible labour found in the “electric servant” narrative is tied up in the exclusionary American dream of the white, middle class home.4 In her 2020 talk “From “Electrical Servants" to #WAP: Appliances, Race, and the American Home”, Edini explores the intersection of racial politics, technology, and capitalism in the advertising of electrical household appliances and the way that they trace the shifts in racialised domestic labour(whereby the work of Black women specifically is devalued and erased) and white America’s class anxieties.

The trad wife trend as it exists today seems to be the next evolution of these movements towards new, more exclusionary fantasies of status and identity made possible through the imaginary of the domestic sphere. I’m not going to link to any of the social media personalities that do this(although I’ve already named a few), but you know who they are. You’ve seen them, you know the way they dress, the way they speak, the image they build. You’ve watched a white woman baking in a too-shiny kitchen in a too-formal gown. The propaganda that is this trad wife fantasy lures viewers into the dream of the pretty dresses and cozy kitchens and happy families and the beautiful past that never really existed. The realities of this labour and the consumer systems and underpaid workers that make it possible are of course left off camera.

Once upon a time, we fantasized about a world where we did not have to work; a world free of the toil of domestic life, where we might have the freedom to be our true selves, or to find love or happiness. But the fantasy keeps changing. We get Peau D’Ane, the story of a princess finding love and happiness while learning to keep house and bake for her fiancé. Middle class white westerners replace undervalued human labourers in their homes with appliances, so the labour is out of sight and out of mind even as material conditions are made worse for those forced to take on that invisible burden in the global majority. We get a girl-bossified Cinderella for the modern age who decides to leave behind sweeping the fireplace so she can achieve her real dreams as a capitalist. Women fight for the right to work and to gain a foothold in the capitalist system. Have it all, break the glass ceiling, labour becomes power. Live happily ever after, boss babe!

And then, of course, women start blogs and post tiktoks about returning to their place in the home, about the dream of the nuclear family and the husband who takes care of them and of not needing to work, about choosing a certain lifestyle. Often these stories are baffling displays of conservatism, or somewhat heartbreaking narratives of the pressures of womanhood, but these strange conservative fantasies have a purpose, and they exist within a specific framework. As Jax Preyer writes about the Ballerina Farm story in “The Imagined Victimhood of Conservative Women”:

“While the story of a pretty Mormon girl breaking free from the church to chase her dreams only to be thwarted by a powerful, controlling man is a captivating one, that does not appear to be what’s happened here. There are ample reasons why a woman may choose to abandon her passions and live out her days declining epidurals, scoring sourdough, and shaking her head disapprovingly at women who get pregnant out of wedlock. In this case, I’m willing to bet it’s got something to do with the whole JetBlue inheritance thing and, of course, a steadfast devotion to the Mormon church. Joseph Smith had a lot more to say about mothers and wives than he did ballerinas.”5

The fantasies being enacted here are closely tied to the cultural context that allows them to flourish in our current social mediascape, and the story being told is about more than just a damsel in distress or a cautionary tale; this fairy tale reflects the world we live in and the conservative politics and capitalist forces that rule it. We just can’t seem to stop dreaming of labour.

Fantasy logic doesn’t work in the real world, of course. There are no magic rings or glass slippers to fit us just right, no magnificent horse or pumpkin carriage to get us out of this mess. And the real world is always infinitely more complicated than fairy tale. Throughout all of these stories, class, race, and gender are the invisible servants keeping the fantasy castle running.

I think what we’ve seen in the reaction to the Hannah Neeleman’s experience recently is only a tiny glimpse of the much longer, more expansive story of misogyny, broken dreams, and human suffering that lies underneath the ideology which she and the ultra conservative, trad communities she is a part of perpetuate. The threads connecting labour and domestic work to fantasy in its many forms(from fairy tale princesses and housemaids to trad cottagecore propaganda) remain impossibly tangled, but we can continue to watch the way that the tale keeps changing, and the invisible forces that are coming out of the margins of the old stories.

il était une fois,

isobel

Megan Agnew, “Meet the queen of the ‘trad wives’ (and her eight children)”, The Sunday Times, 20 July 2024.

Realised upon editing that the scene I’m thinking of specifically was actually a deleted scene lol! I remembered it so clearly from when I used to watch the dvd extras as a kid, but totally forgot it wasn’t in the film itself

Satyasikha Chakraborty, “Technologies of Domestic Labour,” Servants Pasts, European Research Council Funded Project 2015-18. Published online October 2017.

Rachel Edini, “From "Electrical Servants" to #WAP: Appliances, Race, and the American Home”, 25 September, 2020.

Jax Preyer, “The Imagined Victimhood of Conservative Women”, Can I Hold Your Baby? on Substack, 26 July 2024.