Diane, 11:11 am, February 21st. Entering the town of Twin Peaks… I’ve never seen so many trees in my life.1

In the wake of the recent passing of visionary filmmaker, artist, and one of the internet’s best quirky little guys, David Lynch, I’ve noticed a trend of many revisiting and celebrating his career. His body of work is fascinating — films like Eraserhead and Blue Velvet are enduring cult classics, Mulholland Drive has been listed as one of the top ten greatest films of all time, he has a style so distinctive that his name is an adjective2, and I think at least once a week about that interview where Lynch learned that the interviewer had a pet mouse and said “A little mouse, huh? And he’s your pal! Well, isn’t that great.” and told a cool story about a mouse who loved hang gliding.3

But today, we are here to talk about one of Lynch’s most iconic projects: Twin Peaks. Co-created with Mark Frost in 1990, this cult tv series is one I have wanted to watch for years, and I was finally inspired to check it out on a spooky, dark night as I sat at home listening to howling wind and rain while an Atlantic winter storm brewed and slowly engulfed Ireland. In these perfect and ominous conditions, I got my first glimpse of the town of Twin Peaks and its strange, terrible, fascinating world; in the following days and weeks I pretty quickly became obsessed with the show, devouring it at a too-fast pace. But throughout much of my watching, I was constantly reminded of and thinking about another, later beloved(to me!) television mystery show …

the town: a recap of riverdale recaps

the complete list recapping my Riverdale recaps and other Riverdale related essays and newsletters

Classic Cloudtopia readers may recall that I started out on substack writing a Riverdale recap newsletter. Today, I’m here to return to this and share a possibly hot take: I think Twin Peaks is the original Riverdale (and yes, subsequently, that Riverdale is the second return of Twin Peaks.)

Let’s focus out beyond the edge…

A Tale of Two Towns

“Our story is about a town, a small town, and the people who live in the town. From a distance, it presents itself like so many other small towns all over the world: safe, decent, innocent. Get closer, though, and you start seeing the shadows underneath. The name of our town is...”4

In the pilot of Twin Peaks, the body of homecoming queen Laura Palmer is discovered wrapped in plastic on the bank of the river, kicking off an investigation into the mystery of her death that raises more questions than it can answer.

In the first season of Riverdale, the body of high school football star Jason Blossom is discovered by Sweetwater River, and the mystery of his murder unravels a tangled web of secrets in the town.

Both shows focus on and take place almost entirely in the small towns for which they are named. Within these surroundings, we follow the lives of the townsfolk and get to know a broad cast of characters.

The stylistic similarities in both towns are abundant, each being representative of an ideal of small town Americana, from their strange blending of 1950s nostalgia and contemporary fashions, their love of classic diners(the Double R and Pop’s respectively are essential locations in these shows, as are their respective trademark beverages, diner coffee and old fashioned milkshakes), and their fascination with the historic darkness and hidden evils of these places, embodied in murdered children and evil fathers and teen drug deals and shady real estate holdings and the secrets of well-to-do families.

Evil lies at the heart of these two towns.

Shared Influences and Style

Stylistically, there are many connections between the two. Both Lynch and the creative team of Riverdale have a real love for film noir, for 1950s melodramas, for weird horror. These shows, then, have to a great degree a shared film vocabulary that really shapes their style and atmosphere. This can be seen in the storytelling, direction, cinematography, and other elements.

I love the strange, uncanny tone that permeates these worlds, and the campy, soap opera inspired dramatics we see from their inhabitants. As one of my friends recently said to me about Riverdale, one of the things that makes watching these shows so entertaining and so unsettling is the way that dialogue is almost always delivered with the same intensity, so that normal statements and dramatic announcements and jokes are all given equivalent weight. While your mileage may vary with this performance style, and there is a lot of room for debate about how each show toes the line between satire and sincerity in its soapiest moments, it is something that sets the shows apart.

“I have no idea where this will lead us, but I have a definite feeling it will be a place both wonderful and strange”

Curiously, I think that the shows share certain shortcoming as well, and the difficulty of making the strange and melodramatic tones work consistently is one of them. Many have noted the decline of Riverdale’s consistency after the first season, which is much more tightly written and paced than any of its subsequent outings; but Twin Peaks shares the same problem, and the majority of fans agree that its second season falls apart pretty quickly.

There are many points in later seasons of Riverdale that viewers have described as going too far or getting too weird — season three’s organ harvesting cult plotline is a popular one cited, but to that I say, what about when Ben Horne becomes trapped in his civil war reenactment where he thinks the confederacy is winning the war? and Audrey cosplays as Scarlett O’Hara? Riverdale has its share of bizarre serial killers from the Black Hood to the Trash Bag Killer, but Twin Peaks does too, not only its most memorable killer, BOB, but let’s not forget season two’s collection of increasingly chess-themed serial murders. People also tend to make a lot of fun of Riverdale’s penchant for musical moments and characters ‘just randomly singing’, but Twin Peaks is no stranger to unexpected musical numbers(looking at you, James and Leland) and in it’s third season/The Return, nearly every episode ends with a musical performance.

Let’s get Lynchian

AN ACADEMIC DEFINITION of Lynchian might be that the term "refers to a particular kind of irony where the very macabre and the very mundane combine in such a way as to reveal the former's perpetual containment within the latter." But like postmodern or pornographic, Lynchian is one of those Porter Stewart-type words that's ultimately definable only ostensively—i.e., we know it when we see it.5

While it’s one thing to say that these two shows and the two towns within them share a lot of common interests and inspirations, I want to go a step beyond that and think about the ways in which Twin Peaks itself is a core reference point for Riverdale.

Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa and the creative team of Riverdale have made it clear both by their own admission and throughout the show that they are massive fans of Lynch’s work and the original run of Twin Peaks in particular. As Aguirre-Sacasa said in a season one interview, “all roads on Riverdale lead back to Twin Peaks”. From the very first episode, the iconic shot of the town sign is a direct homage to the opening sequence of Twin Peaks. The presence of actress Mädchen Amick as Betty’s mother, Alice, recalls her appearance on Twin Peaks as diner waitress Shelly. Jughead, who constantly references films in his narrative, mentions several of Lynch’s works throughout the show. Season four takes this up to a new level when it introduces Blue Velvet Video, a retro video rental store with a hidden, red curtained, Black Lodge-esque back room and its quirky proprietor, a man named David who assists a mysterious antagonist known as the auteur in creating a series of videos recreating crimes that have occurred in Riverdale.

This is one of Riverdale’s most curious and most Lynchian plotlines. Aspects of the storyline itself seem to draw directly from Lynch’s 1997 film Lost Highway, but as the storyline goes on it seems to have something bigger to say about directors and viewers and more. Through the lens of the mysterious video tapes, we see the hidden darkness of Riverdale in new light as the evils of the town are captured and replayed on film. The twin identity of this antagonist as both ‘voyeur’ and ‘auteur’—first simply watching, recording the shadowy parts of town, then taking control of the narrative through reenacting and performing violent and terrible events — speaks to an interesting duality, one that is also found in how Lynch’s work is perceived and in his representations of evil. In an essay about “The Theme of Evil in the films of David Lynch”6 David Foster Wallace argues the following:

“The fact is that David Lynch treats the subject of evil better than just about anybody else making movies today—better and also differently. His movies aren’t anti-moral, but they are definitely anti-formulaic. Evil-ridden though his filmic world is, please notice that responsibility for evil never in his films devolves easily onto greedy corporations or corrupt politicians or faceless serial kooks. Lynch is not interested in the devolution of responsibility, and he’s not interested in moral judgments of characters. Rather, he’s interested in the psychic spaces in which people are capable of evil. He is interested in Darkness. And Darkness, in David Lynch’s movies, always wears more than one face…

Evil in Lynch’s worlds is a force that is explored and confronted in deeply unsettling ways. Depictions of violence and villainy on screen are horrifying, ecstatic, overwhelming. Lynch does not give us easy answers or a safe moral standpoint, never reassures us as viewers that evil is bad and that we are good for recognising it, or gives us a clear lesson that we can walk away with. No one is safe from or immune to the darkness. Because of this, many critics accused him of being voyeuristic, of being sick or immoral or evil himself. Wallace pushes back against this:

“if these villains are, at their worst moments, riveting for both the camera and the audience, it’s not because Lynch is ‘endorsing’ or ‘romanticizing’ evil but because he’s diagnosing it—diagnosing it without the comfortable carapace of disapproval and with an open acknowledgment of the fact that one reason why evil is so powerful is that it’s hideously vital and robust and usually impossible to look away from.”

This essential quality of Lynchian evil is as disturbing as it is essential, and it is part of what makes the voyeur/auteur storyline so interesting to me — while this figure is given two different names, they are one and the same, the creator of an ongoing project that explores the dark corners of Riverdale’s past and present. What does it mean to recreate evil acts and capture them on tape? Or, as Richard Siken writes in the poem Three Proofs, “When you paint an evil thing, do you invoke it or take away its power?”

There are no easy answers to these questions (and frankly, the way this storyline is wrapped up is not fully satisfying). But these mysteries and the questions raised about Riverdale’s own depictions of violence, and its relationship to Lynchian evil and the broader history of films and television that revel in murder and malevolence, which of course influence them both, are deeply fascinating.

All roads lead back

I’ve said before that the conclusion of Riverdale was the end of an era of great television, a golden age of seven season runs, of terrible teen dramas, of The CW, of seasonal network shows. But if that is true, then Twin Peaks was its beginning.

So much of how we watch and understand television in the 21st century can be traced back to this show — how it operated as a serialized story, its creative and experimental style, its cinematic approach to episodic tv, its ‘water cooler effect’ whereby it became must-watch, appointment viewing that people would discuss the next day. The serialisation aspect was particularly revolutionary and transformative to the tv landscape — at the time, this approach was so unique that co-creator Mark Frost described the story of Twin Peaks in the show as being "a sort of Dickensian story about multiple lives in a contained area that could sort of go perpetually" connecting their new vision for a way to tell an ongoing, unified story in a tv format to the serialization of Victorian novels as a cultural reference point.7

Twin Peaks plays around with genre and tone — its a murder mystery, a detective show, a soap opera, a supernatural drama— yet, as was noted in a review of the pilot in the New York Times, “Twin Peaks is not a send-up of the form. Mr. Lynch clearly savors the standard ingredients,” and perhaps the key to what makes Twin Peaks work at its best is this savoring.

At the core of all of this is a love of storytelling and the ‘standard ingredients’ of television, a love of old films and small town diners and good black coffee and cool jazz and cherry pie. We revel in these moments, devour them. Sincerity is essential, and that same sincere love of the form: great films and little details and so much more is what we find again in all the best moments of Riverdale, carrying on that legacy.

thank you for reading <3

If you enjoy cloudtopia, it would mean the world if you would subscribe, share with a friend, write about this newsletter in your secret diary, etc.

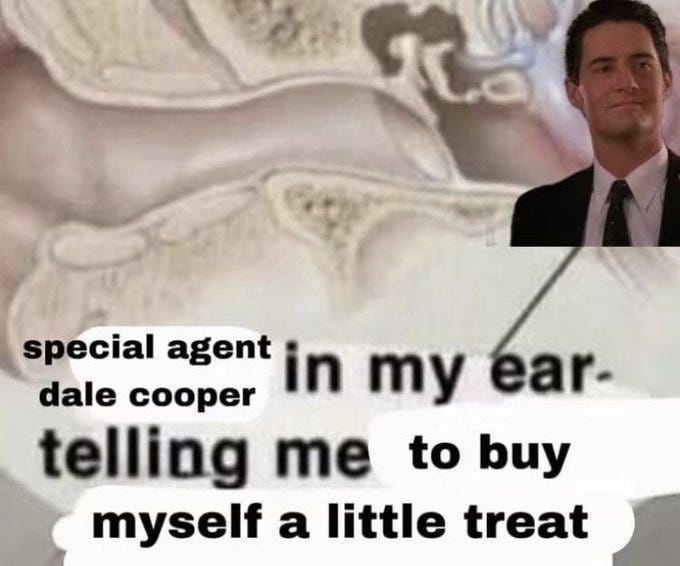

Today, don’t forget to follow the immortal advice of Dale Cooper and give yourself a little present! You deserve it. And as always, stay weird, a weirdo, don’t fit in, don’t want to fit in, never be seen without your stupid hat on, that’s weird.

your riverdale guardian angel,

isobel

From the Twin Peaks pilot episode. Date and time slightly amended to match this publication :)

The adjective in question, of course, being ‘Lynchian’!

Jeffrey Eugenides’ novel The Marriage Plot features a really delightful beat about this phenomena:

"My goal in life is to become an adjective," Leonard said. "People would go around saying, 'That was so Bankheadian.' Or, 'A little too Bankheadian for my taste.'"

"Bankheadian has a ring," Madeleine said.

"It's better than Bankheadesque."

"Or Bankheadish."

"Ish is terrible all around. There's Joycean, Shakespearean, Faulknerian. But ish? Who is there who's an ish?"

"Thomas Mannish?"

"Kafkaesque," Leonard said. "Pynchonesque! See, Pynchon's already an adjective. Gaddis. What would Gaddis be? Gaddisesque? Gaddisy?"

"You can't really do it with Gaddis," Madeleine said.

"Yeah," Leonard said. "Tough luck for Gaddis…”

They turned up Planet Street, climbing the slope.

"Bellovian," Leonard said. "It's extra nice when they change the spelling slightly. Nabokovian already has the v. So does Chekhovian. The Russians have it made. Tolstoyan! That guy was an adjective waiting to happen."

"Don't forget Tolstoyanism," Madeleine said.

"My God!" Leonard said. "A noun! I've never even dreamed of being a noun."

There are so many good David Lynch interview moments like this… what a guy

From Jughead’s opening monologue in the pilot of Riverdale

From David Foster Wallace essay on Lynch for Entertainment Weekly. The full text is available in the essay collection A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again.

See previous citation — this section of the essay is unfortunately not included in the version publication in EW, so you will have to find it on your own </3

Inside Twin Peaks: Mark Frost Interview