“For what is a ghost but that which haunts the empty space that once was full?”

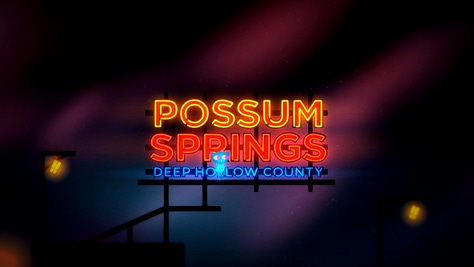

In the 2016 indie game “Night in the Woods”, the main protagonist, a twenty year old named Mae, returns to her hometown after suddenly dropping out of college. She moves back in with her family and reconnects with high school friends, spending her days waking up late, exploring the old paths and closed down storefronts of the town where she grew up, and struggles to find her place in a landscape that has changed in her absence after her plans outside of the town have fallen apart. The game interrogates her struggles with growing up and the ennui of young adulthood, explored through the differing experiences of her group of friends who are all facing growing up, responsibility, and the pain of change in different ways.

There are a lot of interesting elements to this game, from its story and themes, to its rich, complex cast of characters, to its engagement with cosmic horror and supernatural mystery, but what really interests me in the story are the elements about the town, its history, and the ways in which the collapse of this small town impacts the lives of its people, and the shifting memorial landscape that makes up the town of Possum Springs.

“Places can’t control how they are remembered”

The game takes place in the small rust belt town of Possum Springs. Once a hub of mining and industry, the town is in a state of social and economic decline. Local businesses shut down and are replaced by new superstores and chain businesses ‘out by the highway’. This displacement of the economy of the town from its central, shared spaces(the historic Towne Centre, or as our protagonists often playfully refer to it, ‘Towny Centry’ - even in its name, we can see past and present colliding in town’s collective memory) to the externalised spaces of Possum Spring’s periphery exemplifies the sense of displacement and abandonment felt by the people of the town. Where once their economic flourishing and the spaces of daily life were closely united within the walkable area of the town and its neighbourhoods, the removal of businesses and the upheaval of the mining industry and its in-town infrastructure, in the form of the trolleys which once ran in the tunnels underneath the towne centre, has completely transformed the landscape. Now, residents find themselves commuting to jobs and shopping at stores outside of town, both geographically and in terms of relationship with the historical social economy of Possum Springs.

Night in the Woods’ gameplay is really successful in bringing the player into the lived space of the game’s setting. Many of the daily tasks that make up much of the playtime of the game require the player to traverse the neighbourhoods, performing repetitive platforming jumps to reach the rooftops or corners of town where daily activities are completed and characters can be found. The player becomes intimately familiar with the town landscape through these repeated sequences and through the process of exploring the space. While I’ve seen many complain about this, as it can make playing the game feel slow, tedious, or unclear in terms of objectives, I argue that this aspect of the gameplay is an integral part of the experience. By forcing players to go through town everyday, to visit and revisit different locations, and encouraging them to explore and think creatively, knowing that many parts of the story have to be sought out and will not be automatically prompted by the game itself, Night in the Woods creates a sense of immersion whereby the player becomes a resident of the town too, with routines and habits, knowledge and associations with various locations, and actively making choices on when or whether to engage with community members and activities, just as Mae does in reintegrating herself into her hometown. Similarly, the game’s dream sequences reflect Mae’s disjointed experiences of the town’s pasts and present through its unreal, refracted dream spaces, built out of composite landscapes and images from the real world places crucial to Mae’s life.

This encapsulates the way that the spaces of gameplay and the experience of the player moving through them evokes certain understandings about the place and history of the game’s story. The mall that Mae and Bea can visit in an early scene engages in this dichotomy of old and new, and demonstrates how history and social experience manifest in the places of our lives, with the past manifesting and gaining presence in the empty spaces of the present. Shopping malls in the aftermath of their heyday exist as a space of the uncanny, a space purpose built to be the marketplace of the future, creating spaces for capitalism and social engagement, which has instead been confined to the past when malls were abandoned and left to fall apart. We see the dynamics of past and present, and the entanglement of labour and capital in both, in numerous other spaces in the game - the closed down dance hall in town centre, the haunted house turned history museum, or the town cemetery which acts as the final resting place for legendary, ghostly figures in the town’s history alongside loved ones in living memory.

These themes about living with the past and the collapse of the present can be felt not only in terms of the purpose and use of certain spaces in the town, but also in the design. One of the most interesting areas in town is the tunnel underneath one of its main streets, which housed trolley cars that workers would use to travel between the centre of town and the peripheral mines, which was one of the main industries of Possum Springs, and was a core place for great conflict and tragedy in the history of the town (miners strikes, fights between labourers and bosses, the massacre of workers by strike breakers, accidents and mine explosions which killed many townspeople, and the great flood which damaged much of the town and took out the trolley tunnels, never to be repaired) as well as lost community and organisation(labour unions allowed the people of the town to come together for a shared cause, solidarity which helped not only their labour movement, but social wellbeing on a larger scale, followed by the collapse of the mining industry and the loss of connectivity, jobs, and economic stability). The tunnel itself has been reduced from a space of transit and labour, to an empty void of nostalgia and kitsch, and the people who spend time in the tunnel are those trying to find new ways to reawaken its economic potential - a pierogi salesman, or a man who salvages junk from the old flooded tunnels to refurbish and sell - or teens trying to construct spaces of their future within a town stuck in the past. The tunnel walls, however, tell a different story, one that speaks to a past of postwar economic optimism, in the form of large mural depicting workers on their way to now long defunct mines, a triumphalist design echoed in other public spaces that feel relegated to the town’s past.

“I had to stay here and grow up, you went off and stayed the same”

Mae feels the push and pull between past and present, memory and history, everywhere when she returns to town. During an argument, one of her friend tells her that “I had to stay here and grow up, you went off and stayed the same,” a criticism of Mae’s own difficulty with maturing and moving forward in her life, but also reflective of the state of the town itself as we see it during the game. Everything has changed, even as Mae expects the places of her own past memory to be preserved in the struggling and ever changing town landscape, which reflects the emotional journeys of its inhabitants. And this is how nostalgia works, right? We imagine the past as another place, which through our remembrance exists outside of time, unchanging and perfect. But when we return to those places of memory in the present, they are never the same as we imagine or recall.

Through her commentary and journal entries, Mae is almost constantly remembering the way Possum Springs used to be as she traverses the town. She remarks on the stores and businesses that used to make up the town centre, and recalls the world as she remembers it - before she left, or before the flood, or in these other locked away eras of the past that remain stable in her memory. But the reality of the situation is that so much has changed and continues to change even after her return. While she was away, imagining her hometown memories to be perfectly preserved and frozen in time, the real spaces have been changing and growing without her.

Nothing is ever the same as we leave it.

The hole at the centre of everything

The geography of the town is based around a centre and a periphery, a spatial feature that echoes many of the themes and ideas introduced in the story, as represented in the penultimate chapter title, “The Hole at the Centre of Everything.” Towne centre is the core of life in Possum Springs, where homes and jobs are centred, while at its periphery are the mines, the woods, and other towns, and as the centre’s stability collapses, jobs and livelihoods are increasingly pushed out from the centre.

The changing landscape of the town is connected to the story’s image of the universe as a ring and a centre —like a donut, a symbol that appears explicitly in the game, especially if the player chooses to visit Donut Wolf with Angus and Gregg. This same shape is found in the geography of mines that hold such an important space in the history of the town, and become a central location late in the game as a haunted, dangerous space with a literal, endless, bottomless hole at its centre. This shape recurs in built and natural environments alike (the mine surrounds the bottomless pit, the valley surrounds the little town, the town surrounds its centre,) and reflects the emptiness of each space as a lived place as well, where the mines have been emptied of life, residents lose their connections and roots the town, the town’s centre shifts ever outwards and away from itself…

In perhaps its most morbid iteration, we even see this imagery in an optional storyline(probably my favourite in the game) where we learn about the symbolism of teeth in labour movements in Possum Springs’ history - while at the library, Mae can uncover a news article about a violent and unjust mine boss who eventually had his teeth removed in retribution by the newly formed miner’s union he had tried to destroy. Each of the miners in this union/secret society kept one of his teeth and would bring it to society meetings, when all the assembled members would return the teeth to a toothless skull. Years after the mining ended and the society had long since died out, the teeth still exist, and stories told say that the teeth are still used as a symbol of the power of the union against the ruling class, and given as a reminder to bosses or managers who might oppose unions in their own workplaces. Mae can actually find one of these teeth hidden in a safe kept by her grandfather, and if the player does this, Mae offers the tooth to her father at the end of the story, and promises her solidarity in encouraging him to unionise at the supermarket where he works. This is such a compelling story that I find really satisfying to investigate and uncover within the game, as well as yet another reminder of the void at the centre of everything - the empty skull of a capitalist is a lasting memento of the emptiness and destruction left behind the generations of mistreated workers and the failed industries and labour movements that had once allowed the town to prosper. But the teeth, a secret symbol of unity, still remain to fill the void, and there is a sense of hope in the idea that bringing a group of people together could restore something once lost.

“Can you unhaunt a haunted house?”

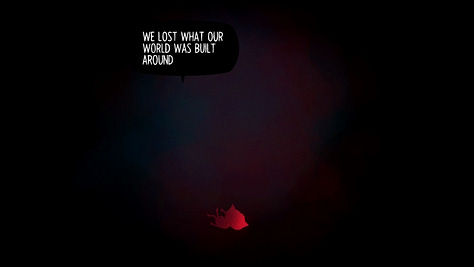

Possum Springs is haunted by its past. We never quite learn whether the ghosts Mae is chasing are real, or what supernatural forces might truly be in power. Yet everywhere across the ever shifting, slowly imploding socioeconomic and spatial landscapes of this town, the haunting forces of both lost prosperity and past calamity, both history and memory, take ghostly shape.

In moments across the game, we learn not just about the official histories of Possum Springs, but also of its ghost stories, its myths, its folklore. Through the constellations above the rooftops and woods, Mae and other characters repeat the lessons of the mythic past of this world. They search for “a god who doesn’t care, and people who do”. At Harfest, a sort-of Halloween celebrated in town centre every Autumn, we hear the legend of Possum Spring’s founding by a group of explorers plagued by a witch’s curse. At the end of the tale, the God of the Forest curses both the witch and the ghosts of her victims to wander the woods and the valley eternally. The town is nestled among woods and rocks, yet struggles eternally with its core emptiness.

“And once haunted, can a place be unhaunted?”

There is an empty space at the centre of everything, here. Call it existential dread, economic collapse, an eldritch god, or Marxist alienation. The spaces of Possum Springs remain haunted and trapped in memory, and it curses those who dwell there always to be trapped, always to return. Always to wander at night, in the woods.

I usually offer a poetry recommendation at the end of my newsletters, but this week, I leave you with a poem that actually comes from the text of Night in the Woods, which the player experiences if Mae befriends her neighbour, Selmers, by listening to her recite silly poems about fruit snacks and changing seasons, allowing her to later attend a poetry reading at the library, where we see Possum Springs from the perspective of Selma Ann Forrester:

there’s no reception in Possum Springs

no

reception

here

I wave my black phone

in the air like a flare

Like a prayer

But no

Reception

I read on the Internet.

Baby face boy

Billionaire

Phone app sold

Made more money in one day

Than my family

Over 100 generations

more than my whole world ever has

world where house – buying jobs

became rent – paying jobs

became living with family jobs

boy

billionaires

money is access

access to politicians

waiting for us to die

lead in our water

alcohol and painkillers

replace my job with an app

replace my dreams

of a house and a yard

with a couch

in the basement

“The future is yours!“

Forced 24–7 entrepreneurs

I just want a paycheck

and my own life – I’m on the couch

in the basement

they’re in the house

and the yard

some night I will catch

A bus out to

the West Coast

And burn their silicon city

to the ground.

hope you’re staying warm and looking at the stars on this Longest Night,

isobel