a quick note before we begin: cloudtopia is best viewed in a browser. if you received this newsletter as an email, you may need to open it elsewhere to read to the end!

I’ve been thinking and reading and writing a lot about the intersections of art and science lately. This week, we’re returning to a topic I first wrote about a little over a year ago: the art of palaeontology1!

Below, you’ll find an updated version of that story, complete with the conclusion that was originally published separately, plus some brand new findings I wanted to share!!

scale

As is so often the case, this all began with a wikipedia spiral.

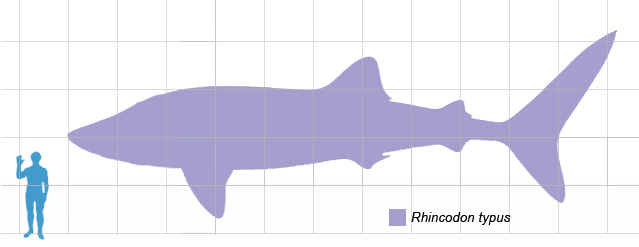

Bored at work one day, I was thinking about animals that are Big and started reading about the blue whale(as we all know, it’s earth’s biggest animal!) which led me to a list of the largest and heaviest animals, which is a delightful treasure trove of other lists to click on, like the list of largest fish(which sent me further into the list of longest fish - the whale shark is at the top of both lists, btw) or the list of largest prehistoric animals and the even more curious article (which has been flagged by wikipedia editors for “outdated information and unreliable overestimates”) dinosaur size.

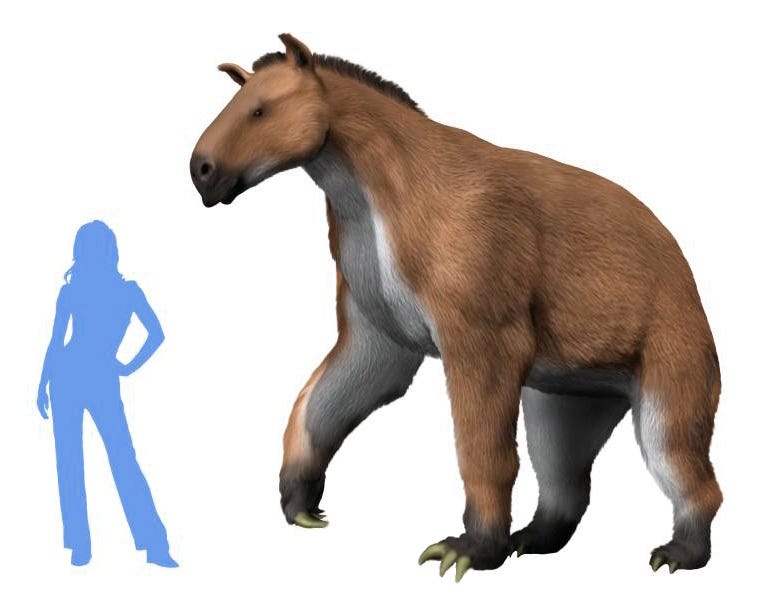

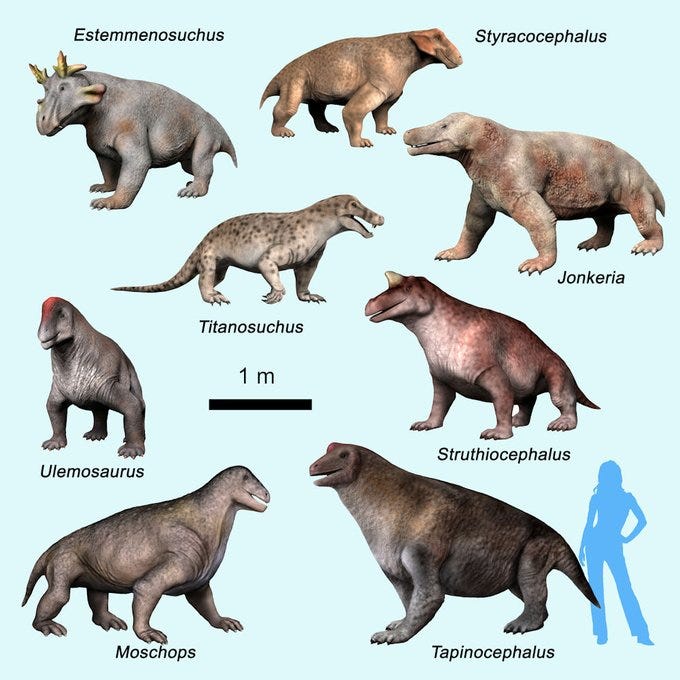

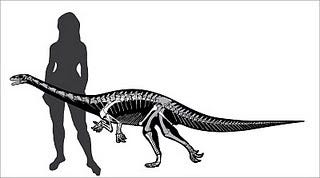

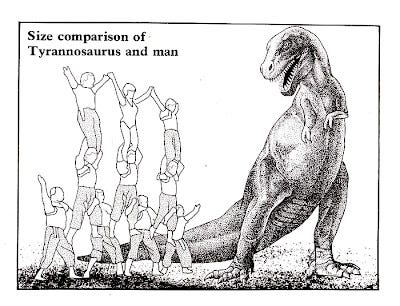

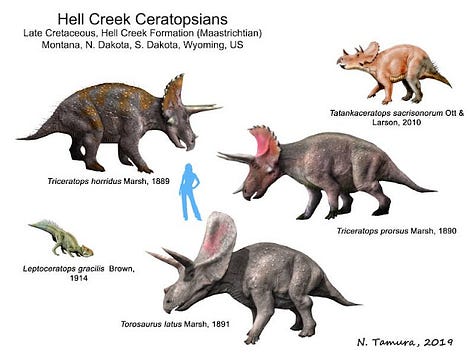

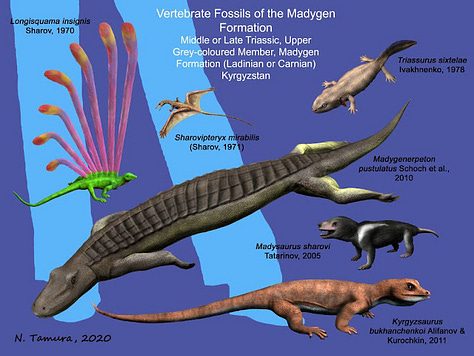

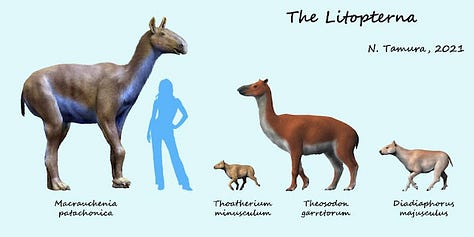

These are all pages full of interesting information and charts and lists, but what really grabbed my attention was all the images, especially of the prehistoric animals - infographics with size comparisons, speculative designs, etc. which do so much to illustrate the information we have about these creatures, and to try to realise the scale and presence of animals we have no way of actually seeing.

And I became fixated on one weird thing: the people for scale.

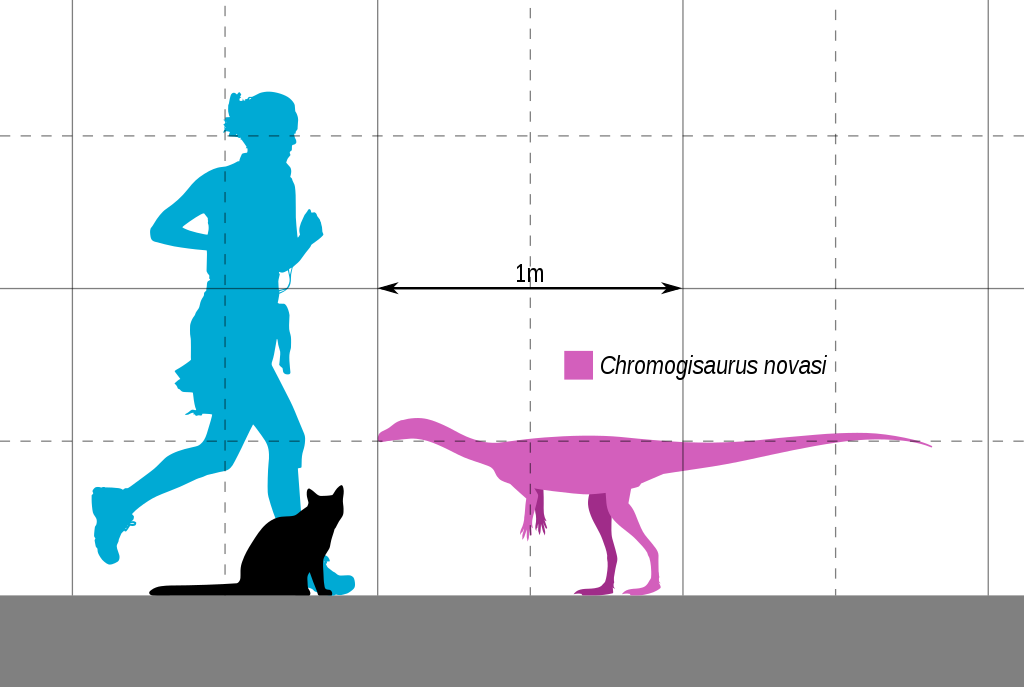

Once you notice them, you can’t un-notice them. They’re silhouetted, non descript, usually “average height”. Yet they often appear distinctly as different characters. A lot of them are just a simple, basic silhouette, designed to give an approximation. In lots of shark or whale images, there’s a scuba diver guy(cool). Sometimes our people-for-scale are doing fun little poses, or waving at the viewer.

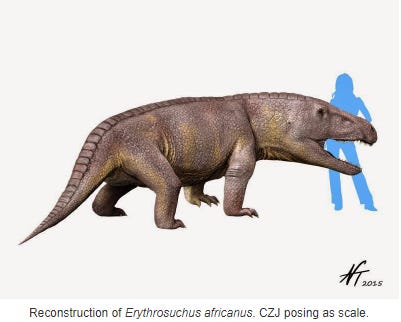

Here are a few other delightful characters from the palaeontological array on wikipedia:

My absolute favourite recurring character in my wikipedia deepdive is this one:

Who is she? The outfit, the hair moving in the breeze, the powerful, sassy pose as she stands so confidently next to this wild Miocene ungulate!

This same silhouette appears for scale in about a dozen other images I found while scrolling through wikipedia lists, but I love the extra personality given to this figure, who’s basically there as a stand-in measuring stick.

Sure, sometimes illustrations get a little fanciful - the person for scale swims in an underwater scene, or might wave a hand instead of simply standing blankly. But this is so specific, so intentional, so fun for a scientific image. Fascinated, I started googling things like “who makes dinosaur scale images” and “who is the person for scale in science diagrams” and other meaningless phrases that turned up absolutely nothing of use. I reverse image searched the blue silhouette, but only got more wikipedia articles with more illustrations, or random websites hosting clearly stolen art.

Circuitously, I found myself back in the wikipedia spiral, and back to the easiest and most obvious way to track down the source: by looking at the source. This was a sad moment for me as a researcher.

Wikipedia sources their images, I finally remembered, and luckily for me, the source behind all of these illustrations is a prolific paleoartist with an excellent blog and a commitment to bettering the paleoart of wikipedia: Nobumichi Tamura

nobu tamura

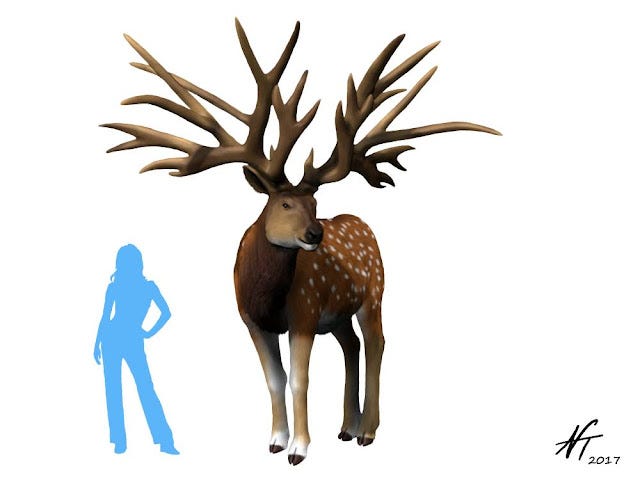

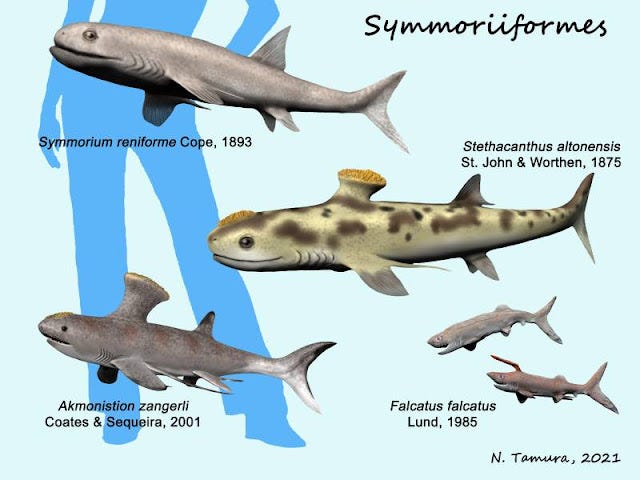

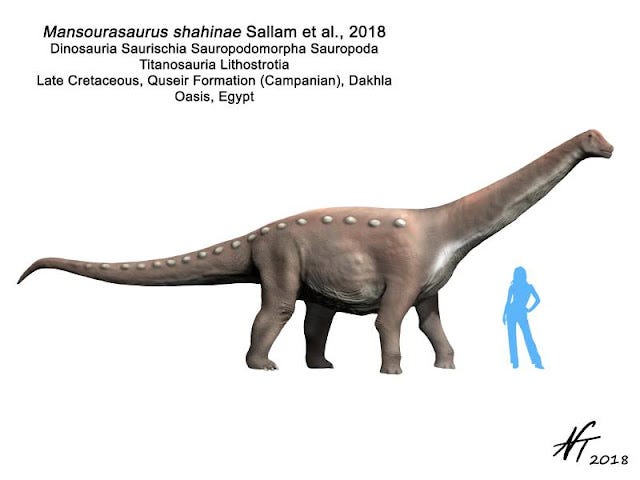

Tamura’s art portfolio is super impressive, extensive, and dedicated to following contemporary research and scientific findings while maintaining creative and original designs. His work is not limited to a specific period or type of prehistoric animal either, but includes a huge and impressive range of creatures, all lovingly and carefully illustrated to give them new life. They are also quite often accompanied by my paleoart bestie, the for-scale supermodel.

Viewing the images directly on his blog, I really appreciate that Tamura includes details about the animal depicted, and makes reference to research and papers related to palaeontological findings, as well as occasional commentary.

For the above, he writes: “The males of this large prehistoric deer from Europe developed extraordinary antlers which look a bit like those of the legendary Pokemon Xerneas.” (This is just one of several Pokemon references I came across in his work.) I love everything about this.

In a 2016 interview, Tamura, who is a physicist as well as an artist, talks about how in the early days of wikipedia he noticed that articles on dinosaurs and prehistoric animals were often devoid of images, and that he wanted to try and contribute, but struggled at first to produce illustrations that met current scientific standards as our understandings and imaginings of these creatures are constantly evolving. As science writer Jacqueline Ronson describes,

“Rather than giving up or finding a new hobby, Tamura just worked harder and smarter, soliciting feedback from Wikipedia editors on how he could better render extinct reptiles. He looked up the latest scientific articles describing the species he was working on and started sketching. He got better.”

It’s really interesting to hear about his process, which has led to the creation of over 1500 illustrations, and the way that these images reflect and are in continuous dialogue with contemporary palaeontological findings. Per Tamura:

Scientists aren’t just collecting and describing fossils — they’re using biomechanical analysis to reconstruct how dinosaurs would have stood and moved around. And advanced techniques are telling us more about the feathers and other soft tissues that would have covered the animals, including pigmentations.

The work of paleoart and paleoartists is pretty extraordinary - they have to blend the imaginary worlds of our envisioned past with the ever changing scientific progress that is being made into better understanding it, and in doing so they help paleontologists and lay persons alike to better see the past, and to try to locate ourselves within and alongside it.

the mystery woman

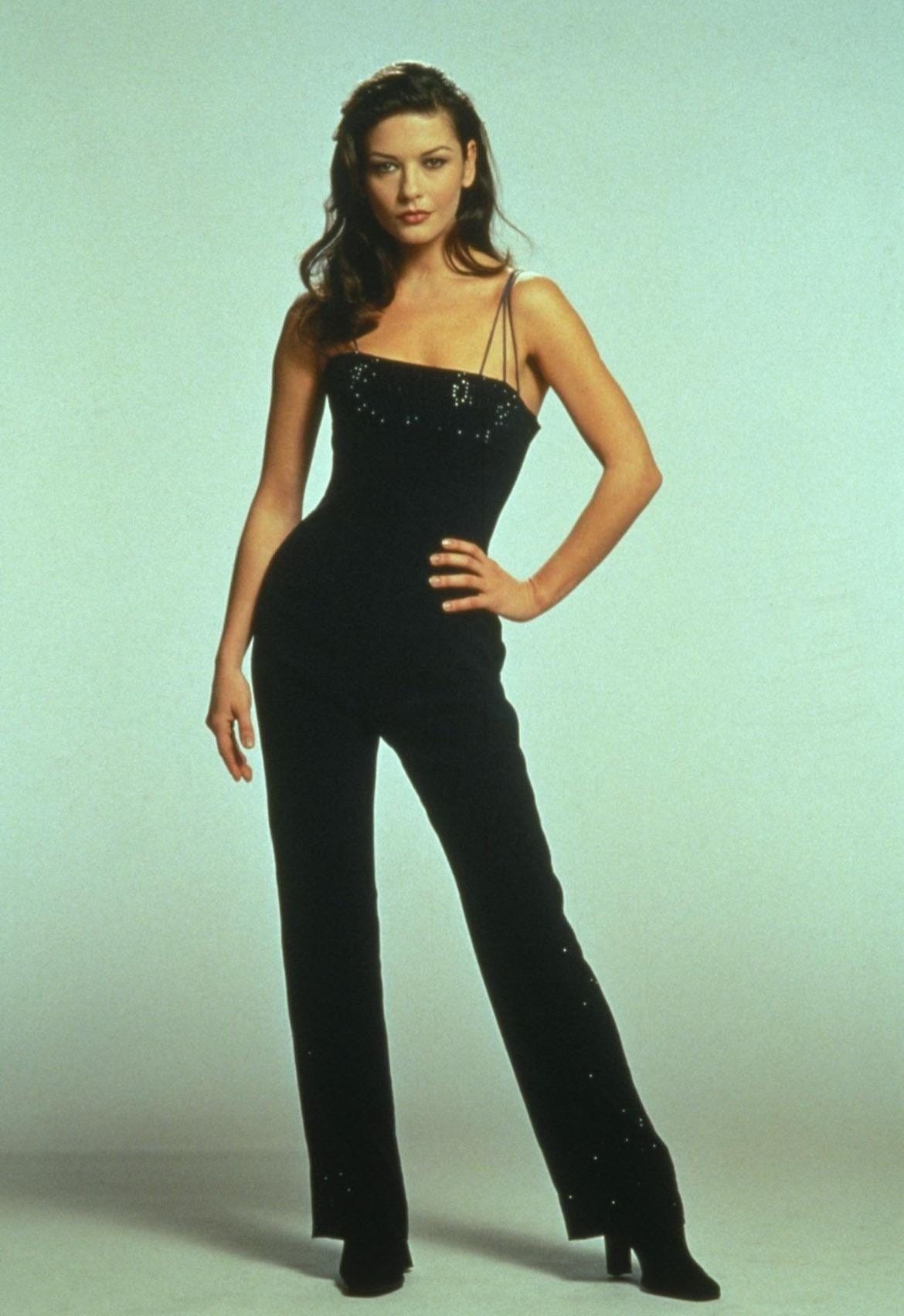

In my deep dive into the wikipedia archives on paleoart, and my discovery of the incredible palaeo illustrations of Nobu Tamura, I have finally found exactly one clue in my search for the enigmatic figure who appears alongside so many dinosaurs and extinct creatures in his portfolio. In a 2015 blog post, the figure is identified in a caption as “CZJ”, which I have to admit I puzzled over for a while, before I came to an inevitable conclusion that the person pictured here in blue silhouette is actress Catherine Zeta Jones?

I wasn’t able to find a source image that matches(yet), but I’ve finally started to unravel the mystery behind this iconic for scale figure. How bizarre and wonderful it is to have images like this to guide our visions of the past! What a world we live in that our Wikipedia articles are being illustrated by the image of CZJ hanging out with an incredible array of prehistoric and extinct animals!

In my original investigation, I left things here, but not long after I was able to find further references elsewhere on the internet and learn a more complete version of the story behind this internet paleoart iconography.

CZJ and the Pioneer Dorks

It turns out that CZJ for scale is not just a quirk of Tamura’s illustrations, but is something of an inside joke among the paleoart community. Here is a blog post from another artist, Matt Martyniuk, from 2010, where he discusses recent trends in the for-scale images being used in the community.2

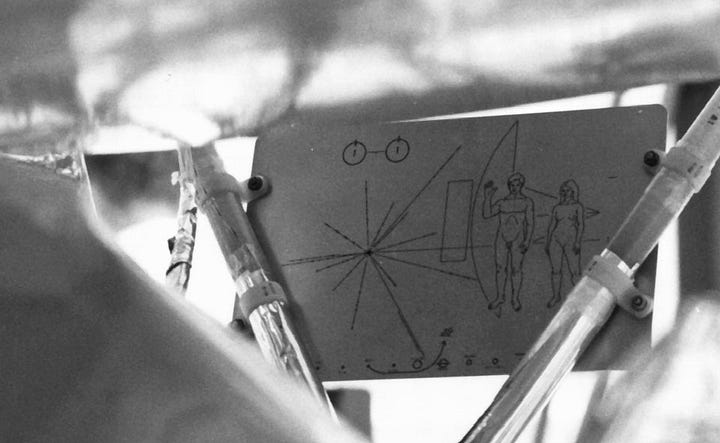

In this post, he talks about the introduction of CZJ as a somewhat controversial inside joke, as well as his own contribution to the community of the waving guy I mentioned in my own findings last week, but who he calls “The Pioneer Dork”. Thanks to this post, I now know the origins of waving guy - his silhouette comes from a plaque that was designed for the Pioneer 10 Spacecraft back in 1972 by Linda Salzman Sagan.3

Finally, I had a new lead on the CZJ mystery - the first ever use of the image, and the discussion around it on the talk page on wikipedia, which goes back to June 2007.

While at the time, the conversation was dismissive of the new trend(and honestly, pretty misogynistic in how they talk about the scale figures, CZJ especially), it’s amazing how this one-time joke has genuinely taken off, and variations of this image can be found everywhere in the palaeoart world online.

The more I have tried to dig into this, the more I find that the scale figures, ubiquitous as they are in this genre of image and in the research work of paleontology, are critically under looked. Almost no one talks about them, and they are very rarely if ever sourced or described when their images appear in research papers, wikipedia articles, or in discussions online. They play such an important role in contextualising these images for viewers, bringing our world and that of ancient and extinct animals into alignment in a way that allows paleontological research to come to life and leap from the buried past of the earth into our contemporary realm of knowledge. Yet almost no one in the community seems to be discussing them. I dug through the archives of paleontology and paleoart communities on tumblr, reddit, wikipedia, twitter … all the places where I would expect people to obsess over these kind of weird, specific details, and yet found pretty much nothing about this topic. Does no one else find this fascinating? Is no one else troubled by this strange, extremely niche internet mystery??

Nevertheless, over a year later and after a genuinely absurd amount of internet sleuthing, the final mystery that has plagued me is solved.

I knew that in returning to this topic, I would need to finally find the final pieces of this puzzle, so I got in contact with Nobu Tamura via email, and he was kind enough to answer some of my questions and confirm the history I had pieced together of Catherine Zeta-Jones appearing in paleoart images, including those created by Martyniuk and Tamura himself. He also told me that while he did not remember exactly where this image originally came from, he had started using it in his work around 2007.4

And finally, the missing piece: I have excavated the original image used to make the CZJ silhouette, which comes from promotional photos for the 1999 film Entrapment.

Now, at long last, after countless google searches, wikipedia talk pages, and hopeless digging through reddit forums, the mystery of CZJ as scale can be put to rest :)

Happily, I can now confirm the origins of this palaeoart icon. And in spite of the odds, CZJ for scale is still slaying in new paleoart almost two decades of paleontological discoveries and paleoart creations later!

art as science

The world of palaeoart is such a fascinating one, and alongside the delightful artwork being produced and disseminated, there are also really interesting discussions in the community around palaeontology and paleoart that guide us to think about the impact and value of these images for scientific enquiry, exploration, and education.

In “Paleoart as Science”, Adrian Currie writes about the impacts of artistic depictions of prehistoric creatures on actual paleontological research, as well as public perceptions, and the ways that the imagery of paleoart serves to shape the way we think about these animals.5 We can even propose that paleoart is not just a tool for illustrating research or aiding in science education, but acts as its own epistemology in the palaeontology realm, where artists are not only making abstract evidence concrete, but engaging in scientific hypothesis and conjecture, playing a key role in the network of physical, chemical, and imaginative evidence that we must put together in the work of reconstructing extinct animals.

“State of the Palaeoart” is a commentary by Mark P. Witton, Darren Naish, and John Conway, which also provides really interesting commentary on the importance of paleoart, and the way that it is undervalued and the inaccuracies and plagiarism that often result in the production of art.6

By the same authors is the book All Yesterdays: Unique and Speculative Views of Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Animals, which has become a contemporary classic in the realm of paleoart and attempts at cataloguing and salvaging the public conceptions of dinosaurs from the decades of poor science, misinformation, and more that have plagued this field.

The book includes fantastic illustrations which demonstrate the ways in which paleoart designs must often make serious interpretive decisions about how they represent abstract data from fossil records, and the ways that this can lead to wildly different and often incorrect results, which can remain in the collective imagination long past the point where paleontology has moved past it. Everything from the Crystal Palace dinosaurs to the monstrous carnivores of Jurassic Park are works of pop-paleoart that shape how we imagine and understand our planet’s ancient inhabitants, often in distorted, outdated, and non-evolving ways. Palaeoart plays an important role in shaping how we think about and imagine these creatures, and new findings and publications work to move our thinking forward and help us to reshape old visions of terrifying tyrannosaurs and misshapen monsters into more complex and scientifically informed concepts of real living animals that once lived on the earth.

image interlude ii

While I still dream of finding out more about the trends and origins of CZJ and other popular scale images(anything before that first image on Wikipedia seems to be lost to time) but for now, our mystery has been solved

But before we wrap up, I wanted to share a few other images I’ve come across recently with fanciful and bizarre for-scale figures.

And finally, a few more very cool prehistoric creatures illustrated by Nobu Tamura:

Art and artists do so much to guide scientific study and discovery, in this field and beyond. From the ongoing discussions in the paleoart community to more recent AI art scandals in scientific journals, we can see the real world implications and intellectual dangers of undervaluing the work of artists in science fields. The paleoart images I’ve been finding in my weird little internet odyssey are strange, magical reminders of the endless mysteries of our world and worlds past, and an incredible intersection of art and science, inside jokes and scholarly exploration!

thank you for reading! if you enjoyed this newsletter, it would mean the world to me if you would subscribe, leave a comment, or share with a friend. I’ll be back with you soon for more art investigations and other future newsletters :)

standing in for scale,

isobel

Paleontology/palaeontology, whatever you want to call it. I think I ended up using both spellings kind of interchangeably in this piece because there are just too many vowels in there for me to reliably keep track of.

Matt Martyniuk, “Dinogoss: Trendsetting.” April 2 2010.

Yes, that Sagan! Linda and her husband Carl collaborated on aspects of the design for the Pioneer Plaque.

Special thanks to Nobu Tamura for taking the time to answer my queries and actually responding to my cold email!!! As readers can see throughout this newsletter, his illustrations are incredible, and what a cool guy!

Adrian Currie, “Paleoart as Science,” Extinct-The philosophy of palaeontology blog, 27 February 2017. https://www.extinctblog.org/extinct/2017/2/27/paleoart-as-science

Mark P. Witton, Darren Naish, and John Conway, “State of the Palaeoart,” Palaeontologia Electronica, September 2014. https://doi.org/10.26879/145